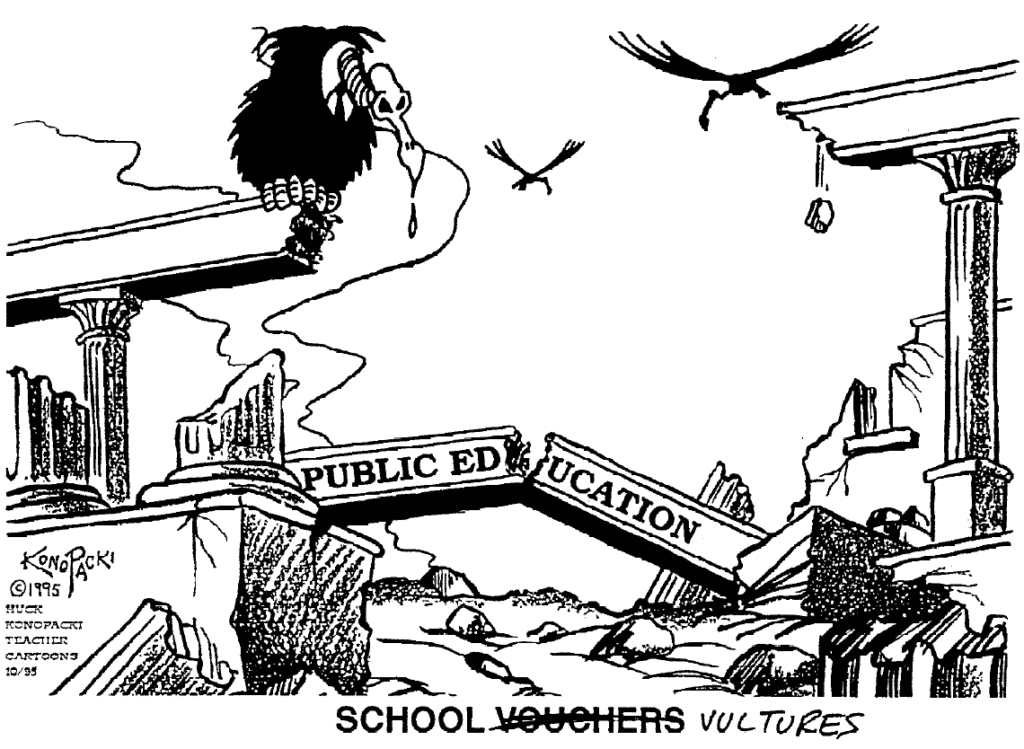

Why the Wisconsin Legislature Approved Vouchers for Religious Schools

What can we learn about recent and new trends in politics from the Wisconsin State Legislature’s recent enactment of religious school choice? Or, more bluntly, why did my side — the opponents of breaching the wall separating church and state — lose?

Whether or not the final Court decision on this case settles if this version of religious school choice is constitutional or not, it’s clear that the supporters of religious school choice will be back in the State Capitols throughout the country with mind-numbing variations on a theme, in an effort to get something, anything, enacted into law. Therefore, it’s important to analyze and learn from Wisconsin’s experience.

The relevant policy background is that four years ago the State Legislature approved a “parental school choice” program for low-income parents living in the city of Milwaukee. That program was limited to private schools located in the city of Milwaukee that were non-sectarian. When Governor Thompson submitted his proposed 1995-97 state budget bill to the State Legislature in February 1995, he included a provision expanding the parental school choice program to include religious schools as well. With that, the battle was joined. During the fight I served as Vice Chair of the Wisconsin Coalition for Public Education, which was the central umbrella for the groups opposing this scheme. Eventually, the legislature not only approved the Governor’s proposal but expanded it in several ways, including moving the starting date up from fall 1996 to fall 1995.

ANALYZING OUR DEFEAT

Why did my side lose? Among the reasons:

- The Republican Party now has captured the public perception that it is the party of “new ideas.” Whether this is true or not substantively is irrelevant. In politics, perception is reality.

Naturally, the corollary of that image is that groups on the other side are viewed as opposing change, being defenders of a “bad” status quo, and lacking any solutions to pressing problems. So, my side started out in a position that is undesirable politically. - For decades, when the Legislature was asked to approve various formulations of “paroch-aid” such as free textbooks, tuition tax credits, etc. they were always defeated. But, the same proposal received a new moniker: “parental choice.” While substantively this was merely old wine in a new bottle, it was politically a winning transformation. With this new spin, the fight was no longer about tax dollars going to religion, but rather about whether one was for or against “parents” and for or against “freedom of choice.” The repackaging and new spin of this old idea was brilliant politics which totally reshuffled the political deck.

- Generally, Americans are sympathetic to the plight of low-income innercity residents — predominantly African Americans — who want to move up the socio-economic ladder through education and hard work. By limiting the benefits of the religious school choice proposal to them, the proponents tapped into this public sympathy. The subtext of the debate became whether an abstract principle of the constitutional separation of church and state was as important as doing something that would ostensibly and concretely help inner city kids.

- There is an odd math in the minds of elected officials regarding constituent lobbying: the few who feel intensely about a proposal carry more weight with an elected official than the many who feel less intensely.

Typically, in this peculiar dynamic of “political math” a legislator hears more from the few constituents who feel strongly about an issue than from the many constituents who feel casually about it. If the elected official votes in the way desired by the small special interest group, its members remember and reward that elected official. The less attentive public may not like it, but it’s just not very important to them.

Conversely, if the elected official votes against the position of the special interest group, its members will go to great lengths to remember and punish the elected official at the next election. The less attentive public may have benefited from the elected official’s position, but is unlikely to remember at the next election.

So, the elected official always is better off politically doing what small groups intensely want rather than what large groups casually want. This odd dynamic captures why special interest groups wield disproportionate power in the American political system.

In the case of religious school choice there was an identifiable and organized constituency to lobby for it since the parents had a clear and tangible benefit that they wanted. In large part, the creation of this constituency was due to an imaginative strategy by the groups supporting religious school choice who also had the financial wherewithal to implement the strategy.

First, Milwaukee-area corporations and individuals were asked to contribute to a program called Parents Advancing Values in Education (PAVE) to finance partial scholarships to low-income parents to attend religious schools in Milwaukee. These were the parents not eligible for state funding under the earlier school choice program, which was limited to non-religious schools. PAVE was funded for five years only. Thus, the families benefiting from PAVE had a tangible stake in convincing the legislature to expand school choice to religious schools before the expiration of the five-year life of PAVE. So, in effect, the raison d’être of PAVE was to bring into being a lobbying constituency that had not been identifiable or in existence before.

Second, the Metropolitan Milwaukee Association of Commerce (MMAC) hired someone specifically to create a lobbying group called “Parents for School Choice.” Her only, and full-time, job was to mobilize parents to lobby the legislature, issue press releases, convene public meetings, organize bus trips to Madison, etc.

On the other side, the Wisconsin Coalition for Public Education had 26 organizational members, but we weren’t a single-issue group focusing solely on this one matter. Rather, we were many disparate groups that were interested in school choice along with many other issues. And, the “hit” of losing would not be felt as tangibly and greatly by us as by the other side. So, the incentives for involvement by our grassroots members were much weaker.

The closest our coalition came to having a constituency that would feel a tangible negative effect of religious school choice was the teachers union — but they, politically, were “damaged goods” in the eyes of most Republican legislators. - Compared to other paroch-aid proposals that were very expensive because they were state-wide in effect, this proposal was relatively low-cost because it only affected a limited population, defined by income and geography. So, it was much harder for us to argue that if only for generic financial considerations the legislators should balk. Our efforts to talk about precedents, the “camel’s nose in the tent,” etc. were unsuccessful.

Some of the groups supporting the proposal had the discipline to be silent about the expansion issue — even if they would have no benefit from the immediate program. They knew that later it could be expanded to include them, but they knew they shouldn’t say that publicly. My side would have pounced, but we never were given that tactical opening. - School choice was included as a provision in the 2,000 page budget bill. By including it in the budget bill, its proponents had several advantages. First, a budget bill is the only “must pass” legislation during a two-year session of the legislature. To use the legislative parlance, by getting on that train, school choice was sure to reach the station.

Second, to be retained in the budget bill, a proposal only needs the approval of a majority of each majority party caucus in the State Senate and Assembly. In other words, a numeric minority of the members of the Legislature controls the contents of the budget.

Third, by being included in a budget bill, the issue never receives the routine scrutiny and hurdles of a separate bill. This specific proposal was never subjected to separate public hearings, separate votes of the standing committees, separate debate on the floor of the Assembly and Senate and, most important, unlimited proposed amendments to be debated and voted on by the entire membership of the two houses as part of floor debate.

The core of the legislative process is the opportunity for floor amendments by the opposition to pursue wedge amendments that clarify, weaken, delimit, gut, or delay a proposal. That was denied to the opponents of school choice — and with good reason. We may well have won had school choice been a separate bill. - Media coverage is often an opportunity for advocates to “get the word out” to the public-at-large in an effort to mobilize public opinion on an issue. For our side, that did not happen in this case.

First, during the 1990s, the definition of news has changed. TV stations are no longer interested in government news. It is considered boring and supposedly drives audiences away. Even newspapers are following that trend and decreasing their coverage of government. What little television coverage there was focused on avoiding what TV producers call “talking heads.” Instead, they wanted good pictures and action. So, a rally of 100 supporters of school choice had a better chance of coverage than a press conference of opponents. Or, a sound-bite from a cute 8-year-old “victim” who was being prevented from attending a religious school is more telegenic than an interview with a professor who opposes it.

Second, what little print media coverage there was on this issue consisted of episodic, incoherent, and truncated reports. At the start of the controversy in 1993-94, the proponents were the initiators, the ones wanting to do something new. Our side was merely reacting. So, initial print coverage tended to give more coverage to the supporters of school choice than the opponents. Our disappointment with the coverage also demonstrated that news decisions were independent of editorial positions, since the two Milwaukee dailies (which have since merged) both opposed public funding of religious schools in their editorials.

Finally, reporters as generalists showed their susceptibility to manipulation on specialized issues with which they’re not — by necessity — very conversant. As long as they can quote someone “on the record” from both sides, they feel they’ve fulfilled their professional obligations. In this context, assertions are treated the same as facts.

For example, a Federal judge in Milwaukee ruled against a lawsuit trying to force the non-sectarian school choice program to be expanded to religious schools, saying that would be unconstitutional. Press reports then quoted a statement from Governor Thompson’s office saying that the ruling would have no effect on the budget proposal because the budget proposal was “different” than what the judge ruled on. That was good enough for them.

SUBSTANCE VERSUS RHETORIC

But look at the substance. In the existing non-sectarian school choice program, state government issues a check that is made out to the school and is sent to the school. In the budget proposal the check would be made out to the parent, but continue to be sent directly to the school. The parent would go to the school and by law would be required to “restrictively endorse” the check over to the school. Is this, from a constitutional point of view, a “different” proposal? But the press didn’t pick up on the significance of these details and my efforts led only to one follow-up “clarifying” story in the Milwaukee daily paper.

Or, proponents kept saying that since under the GI bill it was constitutional for public funding to go to religious postsecondary schools, surely the same would be true for religious elementary and secondary schools. My side kept sharing with reporters and legislators the specific court cases that explicitly ruled that to be not true, along with the reasoning of the courts, but we never received any significant “traction” with the press. Reporters are generally unwilling to exercise a judgment that differentiates between facts on the one hand and assertions or claims on the other.

In conclusion, there were many reasons why we failed to stop religious school choice in the Wisconsin State Legislature. The question is whether the reasons for our failure are inherent and immutable, or whether a different strategy might have led — and could lead in the future — to a different outcome.