Why Is School Finance Equity Such an Elusive Goal?

There are two stories to tell of school finance reform and the three decade old struggle to try to achieve equity in funding public schools. These two stories sound very different.

One story is the upbeat account of the valiant struggles in court for school finance equity and the well-known victories, such as Serrano v. Priest in California, Robinson v. Cahill and Abbott v. Burke in New Jersey, and Rose v. Council for Better Schools in Kentucky. These are the stories of downtrodden plaintiffs and often pro bono attorneys, combining forces with civil rights and other progressive forces, to fight legal battles through numerous appeals and retrials to finally achieve justice for poor children.

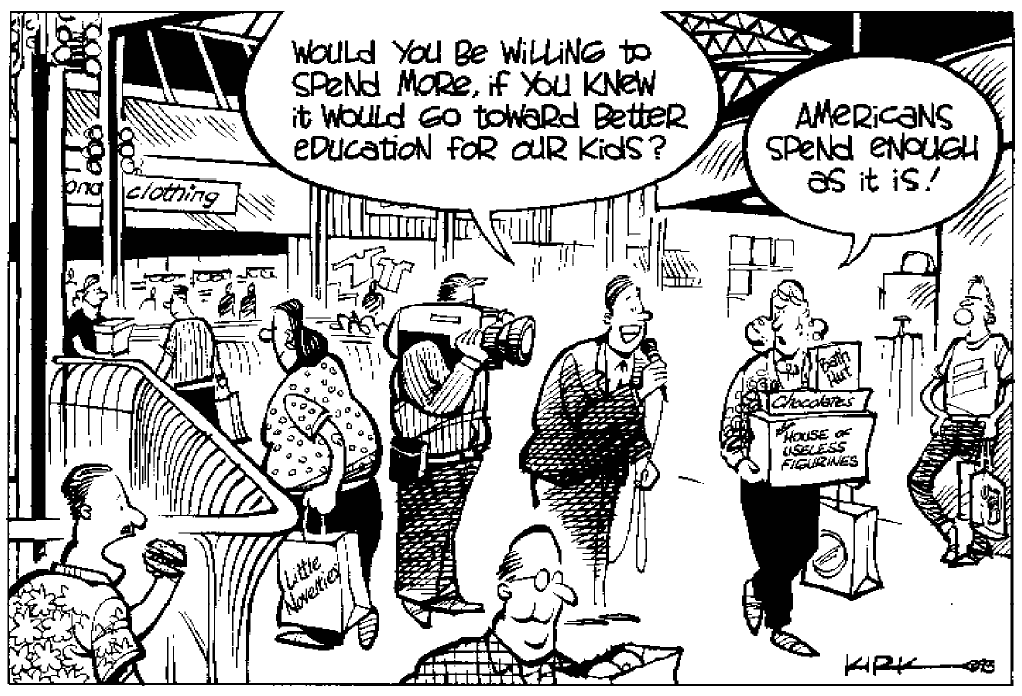

The other story is a bleak tale of numerous court challenges and millions of dollars spent to fight for school finance equity, and little or no progress. This story focuses on recalcitrant legislators, penurious governors, and taxpayers and voters who eventually turn their backs on the plight of poor children living in poor school districts.

The first story is the lore of school finance specialists, civil rights activists, and those who are currently carrying forth new lawsuits against various states. The second story may be closer to the truth. The fact of the matter is that after almost 30 years of school finance litigation, in both federal and state courts, there is scant evidence that the education of one child, or any group of children, has been significantly improved because of these lawsuits.

HISTORY OF LITIGATION

The movement began in the late 1960s, when because of a heightened concern for the plight of the poor and because of some seminal studies by scholars such as Wise and Coons, Clune, and Sugarman, the Ford Foundation and others began to fund lawsuits designed to challenge state school finance systems on the grounds that basing educational spending (and thus the quality of schooling) on the property value of the school district of residence violated the equal protection clause of the U.S. Constitution, as well as equal protection and education articles or clauses of state constitutions. The federal litigation came to an abrupt halt in 1973 when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in San Antonio v. Rodriguez, by a 5-4 vote, that the Texas system of funding schools—as deficient as the Court acknowledged it was—did not violate the U.S. Constitution. The rationale for the Court’s decision was that education was not a “fundamental right” under the U.S. Constitution and that the Texas school finance system was rationally related to the state’s strong concern for local control.

Legal action next reverted to the state level, and during the first wave of state school finance lawsuits in the 1970s and early 1980s a number of notable cases were pursued. By one scorecard, this first wave of suits included 18 states where the highest court ruled on the constitutionality of the state school finance system. The state system was found to be constitutional in 10 of those states, and unconstitutional in eight of the states.

A quick look at some of these eight states might be useful.

The best known case was Serrano v. Priest in California. The state high court issued a strong opinion about the unconstitutionality of the state school finance system because the quality of a California child’s education was based on the wealth of the individual district, not the wealth of the state as a whole. The court mandated equalizing school expenditures for regular programs within a fairly narrow dollar range. By 1986, the courts found that California was in compliance with the Serrano order and that the system was now constitutional.

How was this “victory” achieved? Between the two contrary court rulings, Proposition 13 had been adopted in California, which severely limited local government funding for schools and shifted the financial burden for funding schools to the state level. As a consequence, overall funding decreased significantly in relative terms, and per pupil expenditures in California public schools went from being in the top 10 states in the nation to near the bottom. In other words, California achieved equity by “leveling down” to a lower standard of support for all schools. It can be argued that equity was achieved not by raising the spending levels for the poor, but by lowering the spending levels for the affluent. Who benefited from this victory for equity? Not school children, but taxpayers who saw relatively lower tax bills.

Another early victory was in New Jersey, where the state supreme court declared the state system of funding public schools unconstitutional in Robinson v. Cahill. The New Jersey court adopted a get-tough policy and, after the state legislature dragged its feet in complying with the court’s order, closed down the New Jersey public school system (during the summer months) in the mid-1970s until the legislature came up with an acceptable funding plan. Robinson v. Cahill came to the New Jersey Supreme Court about a dozen times in as many years, with full compliance never being reached.

The successor suit, Abbott v. Burke, finally resulted in a firm equity decision in 1990. A Democratic governor and legislature came up with a tax increase and a funding plan that would have made a significant step toward school finance equity in that state. The public outcry was furious. In the next election the Republicans were swept into power by a wide margin and the equity plan and tax increase were rescinded. Abbott v. Burke is still before the New Jersey Supreme Court, and the situation has not been resolved almost 30 years after the first case was filed.

Similar stories can be told about events in Connecticut, West Virginia, and Texas. Since the mid-1980s, there have been 11 state supreme court decisions, with the system declared unconstitutional in seven and constitutional in four. The impact of the cases has not differed.

The most sweeping case was Rose v. Council for Better Schools (1989) in Kentucky, where the state high court not only declared the state school finance system unconstitutional, but swept away the whole state system of education. The system was rebuilt with a great deal of outside expertise, but the result is far from clear. Some people feel Kentucky has made great strides toward equity and a better educational system, while others point out major flaws in the new system. The real answer is yet to be known, but very few are still predicting that Kentucky may provide the model. The grand plans are collapsing under the weight of the realities of some of the factors I discuss below.

Federal and state school finance lawsuits seem to have been singularly unsuccessful in improving the plight of children trapped in underfunded school systems in poor communities. In fact, a recent study by Indiana Law professor Michael Heise, although exploratory in nature, finds no evidence that successful state school finance lawsuits increase overall state spending for education. All in all, state government leaders, both executive and legislative, are highly reluctant to support legislation which would remedy the situation.

The purpose of the remainder of this essay is to explore the reasons for the singular lack of success in a critical public-policy area and to speculate on how these factors might be overcome. What is there in contemporary American political life that impedes governors and legislators from adopting new state school finance programs, which could provide a substantial level of funding equity in order to help achieve social justice? Why is change so hard to achieve?

PROTECTION OF PRIVILEGE

Those desiring school finance equity have become victims of the “endowment effect.” Legal scholar Cass Sunstein uses this term to refer to the situation in which people are highly reluctant to give up what they already have without a political fight. Economist John Kenneth Galbraith has referred to the same phenomenon as the “protection of privilege.” State school finance formulas are allocation algorithms, which distribute funds to local school districts based on some set of objective factors. If the formula is altered to benefit some set of districts, poor districts for example, the result is formula winners and losers. Unless total funding is increased significantly, some districts get less because some districts get more.

By and large, it is the affluent districts who will lose, and no appeal to altruism or justice will win over the fear in the affluent communities that their taxes will go up and their level of educational services will go down. We also know that residents in affluent districts are more likely to be more politically active, as well as politically more influential, than those in poor communities. The endowment effect protects the status quo.

Related to the endowment effect is what Galbraith terms the “culture of contentment.” Sunstein used the term “status quo neutrality” to describe this same factor. Simply put, people in power see no reason to tinker with the current system; they are contented with what now is. After all, schools in affluent districts do quite well, and there is little sense of crisis.

Status quo neutrality presumes that the current distribution of funds is “natural,” and any effort to change it is viewed with suspicion. Many in political power view the proper role of government as protecting current distributions and not making radical changes in the system. Invocation of the mantra of “local control” is a direct appeal to status quo neutrality and the culture of contentment.

Also, there is the problem of caste, by which I mean fairly rigid separation of people by certain identifiable dimensions. Caste exists in the United States on both racial and social class levels. Caste is an important concept because it stresses a false idea that is part of American mythology: that social class distinctions are fluid and that people easily move from one social class to another. We know that people do not have that kind of social mobility and that there are those who prefer it remain that way.

One of the justifications of school finance reform, and the movement toward student equity in school funding, is the elimination of caste through the realization of equal educational opportunities. There are those who are opposed to the elimination of caste because they fear that they, and their children, will suffer a relative disadvantage. “As long as my children are significantly better educated than your children, your children can never compete successfully with my children for the good things in life,” their thinking goes. Caste segregation maintains a large reserve pool of low-cost labor to do the menial jobs in life. While they will not say it out loud, we know that the thought is: “Better not to have two stockbrokers and two lawyers, but a stockbroker and a gardener and a lawyer and a maid.”

What results is a heavy power-based system where affluent whites use their economic and political power to deny equal educational opportunity to persons of color and to less affluent whites. The system is very difficult to change because those in control do not want it to change. They see no personal advantage in greater educational opportunities for those now denied them.

SUBURBANIZATION OF POLITICS

A cluster of factors, which exacerbate those discussed above, are aspects of the recent suburbanization of politics. While it may not have been demographic destiny that caused many states to recently experience a Republican takeover of their statehouses, demography contributed. The rapid growth of fairly affluent suburbs has resulted in suburban domination of state politics in many states.

In Illinois, for example, only 24% of the state’s total population lives in Chicago. Another 19% lives in metropolitan areas outside of the Chicago area, and 17% lives in the non-metropolitan areas of Illinois. That leaves 40% of the population in the Chicago suburbs. Guess who controls both houses of the Illinois General Assembly? Guess who is opposed to school finance reform in Illinois, and why they are opposed to it?

The suburbs around the major city in the state comprise 41% of the population of Minnesota, 39% of the population of Michigan, and 22% of the population of Wisconsin. This situation is not likely to change, and the suburbanization of politics will remain a major impediment to school finance reform and achieving equity. One state-level manifestation of this trend is the recent school finance plan put forth by Gov. Tommy Thompson of Wisconsin, and made into law by the Legislature. According to an Associated Press analysis, the new system takes funds from poor school districts, including Milwaukee, to give funds to affluent school districts, many of which are suburban.

In the federal budget battles of 199596, largely between the Republican House of Representatives and President Clinton, we see the same phenomenon. Most of the major Republican leadership positions in the House are held by representatives from very affluent suburban districts. These are safe districts for conservative Republicans and the holders are predominantly affluent, white lawyers. They want to either destroy elements of the social safety net or devolve them to the states with inadequate funding. Beneath all the rhetoric of “Republican revolution” is the prevailing message: “We have ours and we have no intention of giving up any more than we must to those who have less.” Central to this way of thinking is the notion that the poor are in poverty because of their own moral inferiority.

This is directly related to a heightened conservative and anti-government mood in the nation. Political scientist Theodore Lowi, in his recent book The End of the Republican Era (University of Oklahoma Press, 1995), points out that a fundamental tenet of conservative political thought in the United States is that government exists to impose morality, and that there is objective good and evil. This leads to a mentality that sees the world in terms of winners and losers and believes that the winning party can ignore the distress of the losers. The conservative mind-set wants to impose good and root out evil. Public schools are seen as bastions of moral relativism, and as protectors of much of what is evil in society. As a result, conservatives are not strong supporters of public schools, except in their own affluent districts, where what some have termed “public private schools” exist.

It is my contention that much of the anti-public school rhetoric that intensified in the early 1980s, pointing out the supposedly abject failures of the public schools, was a direct result of the inability of the conservative politicians to pass tuition tax credits and vouchers in the 1970s. On the national level, the failure of Clinton Administration initiatives, such as health care reform, simply reinforced notions that government can not do anything right and that most government should be eliminated. Greater and more equal funding for public schools flies in the face of this conservative, anti-government mood. We should not be providing school finance equity, according to this way of thinking, but instead should be dismantling the public school system and moving toward privatization of education.

DOES SPENDING MATTER?

We next must confront the issue of whether more dollars for schools will make a difference. Does money really matter? Some conservative economists, caught up in the anti-public school fervor cited above, have produced well-publicized studies that purport to show that differences in school funding make no difference in school achievement. Most of these studies, like those of Eric Hanushek, are based on meta-analyses of other studies, which have the disadvantage of blending a number of different research approaches and methods and obscuring some context-based factors which might be useful. Based on those studies, their authors ask: Why increase funding for poor schools, or any schools for that matter?

However, more carefully crafted research studies have shown that money makes a significant difference when it is well-spent. These more useful studies— those of Ronald Ferguson of Harvard come to mind — look at money spent in particular contexts and assess the value of increased funding in those particular contexts. In particular, we know that achievement will improve when we are able to spend money to attract and retain high-quality teachers and administrators, to keep experienced teachers in the classroom, and to support comprehensive, coordinated programs of professional development for school staff. We know that the “opportunity costs” of teaching — that is, the level of teacher salaries relative to the salaries of those with comparable educational qualifications — is a critical factor in attracting and retaining good teachers. But, for political reasons, many politicians perpetuate the myth that money does not matter in education, and that any attempts to increase school funding are futile and wasteful.

TWO MIDDLE CLASSES?

Another factor is the recent split in the middle class, which is partially a result of shifting global economic conditions. We recognized during the 1950s that the United States was dominated by a middle class, and that part of that middle-class culture was strong support for public schools. We had faith that more and better education meant higher earning power. More spending for public schools was not wasteful consumption, but an important social investment.

Since about the early 1970s, we have seen a dramatic change in this situation. There are now two middle classes in the United States. A professional middle class is doing very well economically, and most people in this class have seen significant gains in their real income over the past two decades. Many in this professional middle class realize that their earning power does depend on a good education; they are what Robert B. Reich has termed the “symbolic analysts,” or what others have called a “cognitive elite.” Many are still strong supporters of public schools because they see the direct relationship between a good education and their quality of life, at least in their own districts. Others, however, have the economic power to purchase either private education or high-quality public education in affluent suburban enclaves, and do not support public schools as their parents might have done in the 1950s. While the professional middle class is the stronger supporter of public schools, their support tends to be limited to districts where there are larger concentrations of such a population. The professional middle-class, like their more affluent neighbors, protect their own self-interest against inroads by the less fortunate.

The other middle class, the working middle-class, does not see it’s earning power based as much on education. They have also experienced a stagnation, or perhaps a decline, in earning power over the past two decades. They are not well educated themselves and many do not see a good education as the road to affluence for their children. The working middle class shows a high degree of alienation, anti-elite sentiment, and anti-government feeling. They are often alienated from the public schools (sometimes for reasons for which the public schools deserve blame) and are anti-tax and anti-government. Again, this translates into lack of support for school finance reform on their part.

The point is that for a variety of reasons, we no longer have the broad-based middle-class support for public schools that may have existed most strongly in the 1950s.

ADEQUACY OR EQUITY?

Many people believe that schooling should not necessarily be equal among schools in an area or state, but merely that all should have access to an adequate education. This is what I call the “threshold principle.” Once this threshold of adequacy is reached, these people believe, then unequal education above the threshold is defensible. Since most people have little direct knowledge of schools outside their own neighborhoods, people accept the notion that all schools are at or above the adequacy level. This threshold principle was a critical factor in a New York school finance case, Levittown v. Nyquist (1982), in which the state’s highest court upheld the constitutionality of the New York system of school finance because the plaintiffs could not show that even one child in the state was receiving an inadequate education as a result of the school-funding system.

In her writings on democracy and education, political scientist Amy Gutmann supports this general principle. She questions whether equality of education needs to be guaranteed once all children are provided an adequate education up to some threshold level, although indications are that Gutmann would set the threshold at a fairly high level. Gutmann, a strong supporter of education as a key component of a democratic society, simply does not believe that equality of spending above a certain level of adequacy is required, and many courts have confirmed this view. It seems to me that this is a perfectly defensible position to take, but it does undermine the basis of much school finance litigation.

PROBLEMS WITH LITIGATION

A final factor I will mention relates more to the problems of school finance litigation than to the political context for school finance reform. The failure of many school finance reform cases—cases in which the plaintiffs have prevailed— is that the courts have never been able to provide meaningful standards on what would be the characteristics of a constitutionally acceptable state school finance system. Without clear standards to follow, legislatures procrastinate and often try to minimally change the system to achieve compliance. This leads to further litigation and conflict. In one instance where a court did try to offer clear and explicit standards, Pauley v. Bailey in West Virginia in 1982, the public resisted raising the funds to implement an intricate system of reform specified by the court. Of course, in West Virginia this was the result of a set of standards that were so highly detailed and specific that many among the public thought they were unrealistic, and many educators thought they were an improper intrusion into their own decisions. At least one line of legal argument suggests that courts should resist ruling on issues in which they cannot provide meaningful standards for constitutional compliance. However, if they do provide standards, those standards need to be seen as legitimate and realistic.

OVERCOMING THESE PROBLEMS?

In the face of all these factors working against the attainment of school finance equity in the United States, how might advocates of social justice overcome them?

I believe that the answer to the problems of inequitable school funding has never rested in the courts, but in the democratic process. Ironically, this is the same argument that some state courts (e.g. Illinois) have used to rule against plaintiffs in school finance cases. They have held, in essence, that school finance reform is a “political question” best resolved by the governor and the legislature through normal political processes. However, this should not keep us from considering the proposition. The problem with this approach is that, because of the factors discussed above, a majority of the voters in most states probably do not accept the legitimacy of school finance reform to achieve equitable funding for all.

Numerous political scientists have argued that public discourse in a democratic arena is the proper place for the resolution of public policy issues. This exchange of reason in the public sphere provides an education of the citizenry at large and supports the legitimacy of the decisions reached. The problem with this ideal is that we must factor in the element of power. Political power is not evenly distributed, and those very communities and individuals who would benefit the most from school finance reform are those with the least power.

It has been observed that the United States is the only Western, industrialized nation where the less affluent vote in lesser proportions than do the affluent. Simply put, electoral mobilization of those who would benefit from progressive public policies, like school finance equity, is a necessary factor in achieving equity. Electoral mobilization requires a view of citizenship recognizing that all citizens have a duty to engage in political deliberations, to maintain open access to the political system, to advocate for enlightened public policies, and to vote. A good system of education is a necessary component of active and informed political participation, and would be the beneficiary of such a level of participation. The clearest evidence that a majority of the people have not accepted this view of citizenship is the low turnouts in school board elections. They either believe that school board elections are not important, or they believe that it does not matter who is elected to school boards. Whatever the belief, the result is disengagement of the people from popular governance of school districts.

Many researchers and commentators have studied this phenomenon and speculated about the reasons for this political disengagement. One factor is the view— which is probably realistic—that the holders of economic power enjoy a disproportionate influence in the electoral process in general, because of the impact of lax campaign finance laws, the use of expensive polling and media communication, and the disconnection of many politicians from local political organizations. So, why bother when you feel powerless?

In a recent issue of The American Prospect, political scientist Robert D. Putnam identifies the pervasive role of television in American life as the major factor in the decline in civic life and culture in the United States. He argues that unless we find a way to “boost civic engagement,” the United States will see even fewer people civicly engaged in future decades.

In many instances, those who could gain the most from the types of school improvement that equitable school finance reform could provide are persons of color, the poor, and others who are denied many of the fruits of a productive society. However, the alienation from public schools of many in the working middle class must be overcome. The working middle class has a common cause with minorities and the poor, but that common cause has not always been evident to them. As the bond between level of education and earning power becomes stronger, all groups should see the importance of education as a personal and social investment. If the major factors working against reform are going to be overcome, these are the people who need to be politically mobilized to support political movements toward school finance reform. These are the people for whom access to high quality education would have the greatest payoff.

Those who could mobilize for school finance equity are geographically located in rural areas, urban areas, and many of the older suburban regions of metropolitan areas. Thus they are in a position to wield political influence across a broad geographic base. Just as the Ford Foundation, the National Urban Coalition, the League of Women Voters, and other groups in the 1970s coalesced to support school finance reform cases, similar foundations and civic groups must engage now in vigorous and coordinated campaigns for active citizenship, and for the electoral mobilization of those who are not currently empowered. Only then will we have any hope of achieving equitable school funding through the democratic process.

If Putnam’s thesis about the role of television in civic engagement is correct, then we may be facing insurmountable barriers to political mobilization. The nation may have become so decentralized and fragmented that a broad-based popular movement, like the Civil Rights Movement, may be less possible now than a generation ago. The best lessons, however, may come from the Religious Right, whose leaders have effectively mobilized millions in the electronic age through very sophisticated and powerful use of television, radio, and mass marketing techniques. Key to this movement, though, has also been grassroots organizing through local churches. Rather than turn to the Civil Rights Movement, might we not look to the rise of the Religious Right for lessons? Writer Amy Waldman suggests we may need a “religious left” to re-establish a moral claim to social justice that speaks to fundamental American religious values.

Teacher unions and other groups of organized school employees are examples of organizations which currently exist and which could play a central role in the political mobilization of minorities and the poor, though it is unclear whether they will or not. They have much to gain by exercising a leadership role in this endeavor, and they already have the expertise in organizing. To the extent they are affiliated with the organized labor movement, they can call upon their allies to assist. Pat Robertson has described the Christian Coalition as the “army who cares,” but an active progressive coalition for education, led by teacher unions and other forces for positive change in schools, could lay a stronger claim to that title.

In too many places, however, teacher unions, as well as other unions, are seen as protecting their own economic interests more than they are viewed as the vanguard for social justice. In too many places it seems that teacher unions are part of the “iron triangle” of superintendents of schools, building administrators, and unionized teachers who cleverly and purposefully keep parents and students (and often school board members as well, as I can cite from personal experience) out of the decision-making processes of the system, in order to protect their own privilege and position through maintenance of the status quo. This deafness to the public by the iron triangle of the schools is exacerbated if the public consists of people of color or the poor.

The economist William M. Dugger describes an enabling myth as one based on a half-truth or distorted truth which allows those who benefit from the status quo to continue to do so. A current enabling myth is that the typical public school is not doing its job. This allows those in power to continue to underfund many public schools, while maintaining well-funded public schools in places where those in power reside, such as in affluent suburbs.

One way to counter this tendency is to work to give public schools back to the community by fostering — indeed, by demanding — broad public participation in the affairs of local schools. The local school may be the one place where all in the community can come together with a common interest and a common cause: to mobilize politically for better education and increased school funding. This type of grassroots organizing is not easy, and it will be resisted by those who will lose power if it is successful. However, until those with a direct stake in schools demand a voice and insist on high educational standards for all children, as well as accountability from educators to ensure that all children are able to meet those standards, the chances for significant change seem dismal.

It seems unlikely that change will come through the courts. Tocqueville talked of “a democracy rooted in a civic society,” and praised the civic society he saw in the United States. Whether that civic society ever really existed is a matter of contention, but we need to build that civic society now. We need to build a civic society in which everyone chooses to participate fully in public discourse, in the exchange of reasons, and in voting. That means opening up free access for discourse, for exchange, and for voting. The courts should be more vigilant in removing barriers to democratic participation in a civic society, so that we will have a better chance for governors and legislatures to enact progressive public policies like equitable school finance systems.