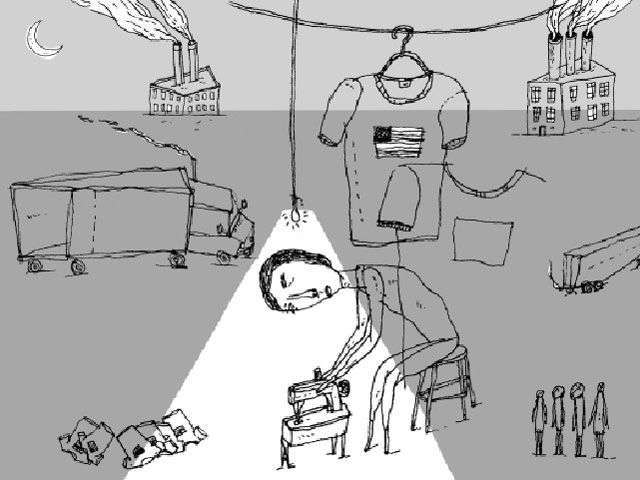

Sweatshop Accounting

A high school teacher shares lessons on economic justice with his business education students

Illustrator: Jordin Isip

My students are out of their seats again. They’re digging into backpacks, flipping down the collars of their Old Navy t-shirts and pulling off their shoes, looking for those little “Made In” tags. Made in China. Made in Vietnam.

“Hey, I was made in Vietnam,” says Allan.*

The students stick yellow Post-It notes on a big map of the world, marking the countries where their stuff was made. In five minutes, the Post-its obscure the coast of China, plus the Philippines, Malaysia, Indonesia and other low-wage countries where people struggle to live on as little as $1 per day.

This isn’t social studies class. It’s business education. The students are examining the connections between their habits as consumers and working conditions in the countries where the goods are made. As I teach students who hope to be future business leaders, these connections, which are often ignored in business education classes, are the central focus of our classroom work.

Today’s high school students can take classes their parents never considered until college, like marketing, economics, and international finance. But this 21st-century curriculum needs to be taught as more than a set of technical skills. In our $31 trillion global economy, business decisions affect billions of people. That’s why I think it’s more important than ever for business education to connect economic skills with the values of democracy, social justice, and environmental sustainability.

That’s what my accounting students are doing as they analyze the pattern of yellow Post-It notes on our classroom map. I ask them what they think the pattern shows. “Use what you’ve learned about accounting,” I say.

Allan waves his hand. “Companies are cutting their salary expenses,” he says. “They can do it by hiring people in developing countries who will work for not much money.”

Allan sees the connection between the numbers on the income statement he is studying and people on the other side of the planet. That’s because I supplement our textbook and its columns of worksheet numbers with readings, role-plays, videos, discussions, and writing about social responsibility. As we learn how the numbers work, we also take time to look for the people behind the numbers.

Sweatshop Accounting

My students are learning what our accounting textbook calls “the language of business.” As they gain fluency, they start talking about debits and credits, business transactions, and financial reports. It’s a cross-cultural language spoken by business people worldwide. The key word in this language is “profit.”

“When we format a company’s income statement, where do we report net profit?” I ask the class.

After some near-miss answers, Mei Li says, “It goes on the bottom line.”

“Right. And what is the bottom line?” I ask her.

“It’s total sales minus total expenses,” she answers.

“Spoken like an accountant,” I say. “But I’m looking for a broader meaning. What does the phrase mean in general? Like, ‘The bottom line is you need a college education to get a middle-class job?'”

More near misses, then Mei Li ventures, “The most important thing?”

Bingo.

I want students to think critically about what can happen when profitability becomes the most important thing. Decisions based on business considerations often are presented as if they are “value neutral” — just part of doing business. Nothing could be farther from the truth. I use a lesson called “Sweatshop Math,” from Rethinking Globalization, edited by Bill Bigelow and Bob Peterson, [See page 61 to order.] to illustrate the human consequences when business managers focus too narrowly on the bottom line.

To help visualize people living and working in other countries, we watch “Sweating for a T-Shirt,” a video by Medea Benjamin and Global Exchange. Then, the students read short vignettes from Rethinking Globalization about the lives of workers in low-wage countries. Using information from the reading, the students label maps of the world with summaries of local working conditions, wage rates, and hours worked. For example, one vignette tells about workers in El Salvador who “get paid 29 cents for each $140 Nike NBA shirt they sew. The drinking water at the factory is contaminated. Women raise their babies on coffee and lemonade because they can’t afford milk.”

As the students cut and paste labels for their maps, I help them reflect about what they know. Their ideas usually echo views they’ve heard before.

“If somebody takes a job it’s their own choice. It must be better than what they were doing before,” says Rob.

“They should go on strike,” says Brian.

We talk about the loss of traditional jobs, suppression of labor unions, and the pressures of global competition.

“This is making me uncomfortable,” says Alicia. “Maybe I don’t want to be in business if you have to take advantage of people.”

“So, let’s use our business skills to see if we could give those workers a better deal,” I say.

We visit the website of the Clean Clothes Campaign (www.cleanclothes.org) to get some real-life accounting data. The site has a photo of a $100 athletic shoe labeled with all the costs that go into its retail price, including production costs, advertising, and profit for the company that owns the brand name. Soon, the students are transferring the data to Excel spreadsheets and using the program to make colorful bar charts.

Brian is shocked. On his chart the 40-cent bar representing factory worker wages is barely visible. There’s a long, $13.50 bar for the brand-name company, and an even longer $50.00 bar that goes to the retail store. With such a visible and familiar example the students immediately see options for more equitable distribution of income.

“They could pay the factory workers twice as much and it would barely dent the shoe company’s share,” says Brian.

“Or cut advertising expense by not paying Michael Jordan so much to wear the Nike logo,” adds Linh.

“Reduce the retail store’s costs,” says Desiree. “That’s the biggest cost.”

I remind Desiree that with her knowledge of fashion, she might want to work in retail sales. “Your paycheck would be part of the retail store’s costs. How would you feel about taking a cut in salary?”

“Oh no! They won’t be taking it out of my pocket,” she says.

Desiree gets a laugh from her classmates. But the students are beginning to see that global economic connections involve decisions that challenge their own values.

Mom and Pop vs. the Big Box Store

After looking at how financial decision-making affects people in faraway countries I want my students to see how doing business by the numbers also changes lives in our own communities. So, as my advanced accounting students study the ownership rights of corporate shareholders, we take time to compare and contrast the interests of shareholders with the interests of local communities. In a unit I call Mom & Pop vs. the Big Box, we read about competition between neighborhood “mom and pop” stores and the world’s biggest “big box” store, Wal-Mart Corporation.

We read parts of the Wal-Mart Annual Report. It says the corporation’s “job is to see how little we can charge for a product.” It describes exciting career opportunities for its workforce of diverse, respectful, well-trained “associates,” including 300,000 outside the United States.

Quang is impressed when he finds a list of Wal-Mart financial contributions to Boys’ and Girls’ Clubs, the United Way, and other local charities in neighborhoods near Wal-Mart stores. I ask him to create a “local citizenship” ratio to compare the amount Wal-Mart spends on community relations with its total sales for a typical store. Quang is less impressed when his calculator shows a ratio that’s a tiny fraction of one percent.

Next, we compare the company’s self-portrait to one of the many critical reports about Wal-Mart’s business practices around the world. As an example, here is a quote from the website of Wal-Mart Watch (www.walmartwatch.com), an organization that encourages consumers to shop at stores offering employees “good jobs with living wages.”

There are two ways to cut costs. You can reduce waste and inefficiency. That’s great. It’s what makes the market system go ‘round. But you can also cut costs by putting them off onto someone or something else. . . . You can muscle down your suppliers’ prices, so they have to move production to poor communities and pay wages that won’t support a decent life. You can hire part-time workers with no benefits and give them no training. Our taxes and insurance fees will pay for their health care . . . . You can pressure towns for tax breaks and free roads and water lines and sewers. The other taxpayers will pick up the bill. You can pay only a fraction of the real costs of materials and energy. Nature will eat the damage. This kind of cost cutting not only imposes injustices on others, it also undermines the market economy. It distorts prices so consumers cannot make rational decisions. It rewards bigness and power, rather than real efficiency.

This statement and the company’s annual report provide a great opportunity to “compare and contrast” texts. The Wal-Mart Watch text describes how Wal-Mart creates low prices by avoiding costs for labor, health insurance, and the environment. The costs don’t go away, but the company leaves them out of its own accounting. It makes them “external costs,” or “externalities,” that will be paid later, or by someone else. Wal-Mart avoids taking responsibility for externalities. Our textbook doesn’t mention this concept. It might be considered too advanced for a beginning course. I think it’s pretty basic, so I introduce it here and return to the concept again and again.

The next day I hand out role-play instructions for a make-believe community meeting, including short character sketches I put together. In this role play, available at www.rethinkingschools.org, students play Wal-Mart executives, city planning officials, shop owners, shoppers, neighborhood residents, and potential store employees.

When we’re ready to begin, I shout, “Action!”

City Planner Mei Li introduces the key speaker.

Quang stands up to make his presentation to the community. He unrolls a large sheet of paper representing the plan for a 100,000 square-foot Wal-Mart Super Store.

“We want to build this great store across the street from the Martin Luther King Mall. It will sell everything you need, at low, low prices!”

My students shop at Martin Luther King Mall. They visit African American-owned hair-styling boutiques, a dollar store owned by a Vietnamese family and a dozen tiny restaurants and shops.

“Hey, wait a minute,” says Alicia. “My friend’s aunt owns a deli sandwich shop on that street. What if all her customers start going to Wal-Mart? She’ll go out of business.”

“Forget those raggedy stores at King Mall,” says bargain-shopper Desiree. “I want to go to one store with good prices. It’s convenient.”

“Yeah, and they might hire minimum-wage teenagers,” says Rob.

Many of the shoppers and residents agree. Some say they’ve shopped at the local stores all their lives, but even they are impressed by Quang’s promise of low prices for everything they need.

Later, reflecting about what we learned during the role-play, the students realize that most of their opinions were based on personal considerations. Nobody stood up and cited Wal-Mart’s income statement to show the connection between low prices and low wages. Nobody argued consciously about “externalities,” although some students were getting at it when they mentioned shopkeepers that might go out of business if the supercenter opened. Next time, I’ll find a more concrete way for students to correlate their concerns with the financial considerations affecting their community. Maybe I’ll cast someone as a labor activist. Neverthe-less, the make-believe community meeting reflected real life. It was clear that by focusing narrowly on a low-cost business model, discount stores like Wal-Mart — and discount shoppers — would sacrifice important social values.

Full-Cost Accounting

What if the accounting system changed to include, rather than exclude, social and environmental costs? From the European Union to Japan to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, government agencies and innovative businesses are experimenting with ways to do this. They call it “environmental accounting,” or “full-cost accounting.”

I want my students to get a taste of how full-cost accounting could work, so I announce that it is snack time. We share slices of crisp, juicy apples, taken from two paper plates labeled “Local Organic,” and “Imported.” Then, I ask the students to discuss their ideas about the costs to bring each type of apple to the table.

We chart the entire life cycle of the apples, listing all the various costs involved in growing, transporting, and marketing the product. Dividing into small groups, some for organic apples and some for imported varieties, the students compete to see who can make the longest, most complete list of costs. In a second column, the students mark an “I” for costs they think are included in the price of the apple, or an “E” for costs they think are externalized.

I hear debates about water, organic fertilizer, and pesticides.

“Where do imported apples come from?” I ask.

“Australia!” “Mexico!” “Chile,” they answer.

“Then don’t forget the fuel for long-distance transportation, and the exhaust and traffic jams,” I remind them.

We consolidate the group lists on the white board. The organic and imported lists look pretty similar — land, water, farm worker labor, a store. But the students begin to find differences, too.

“You can use a truck to get Washington apples to the store, but you need a ship for apples from Australia,” says Ramiro.

“Organic fertilizer doesn’t pollute, but non-organic ones might pollute,” says Grace.

The groups think most of the costs, even highways and seaports, are included in the price of an apple.

“Diesel fuel taxes pay for highways. The store includes that in the price of the apple,” says Rob.

But we find some externalities, too. Business doesn’t pay for more air pollution when they burn more fuel. They don’t pay if chemical pesticides get into groundwater. If companies were held fully accountable for these costs, they would have stronger reasons to adopt better practices.

Apples provide an accessible example. Full-cost accounting gets far more complicated in industries like forestry, mining, or energy. I ask for some general conclusions and trigger a short debate.

“Companies will have to pay for the damage they do instead of leaving their mess for somebody else to clean up,” says one student.

“Yeah, but that will make everything more expensive,” argues another.

We try to reconcile these two views and realize that the costs wouldn’t change; they’d just be assigned to specific products. That would make their prices more realistic.

“If my business had to pay for all the social and environmental costs, I’d try to treat people and the planet better,” says Rushawn.

Driven by the Market

Do corporate executives really want to promote social justice and environmental sustainability? Maybe there is something in the rules that stops them. The “Transnational Capital Auction” activity from Rethinking Globalization reveals part of the answer. Student teams role play as representatives of developing countries trying to attract foreign investment. They must bid against each other to win new factories and jobs.

As business students, my students know what investors want: lower costs and higher profits. They quickly learn how to play the game.

“Build your factories in our country!” they say. “Our people are happy to work for $1 per day. We don’t allow unions. We’ll cut your taxes. Forget about environmental regulations!” Within reason, country-teams that compromise social and environmental conditions to reduce business expenses win the prize of foreign investment. After several rounds of bidding, virtually all of the countries discover that they have been competing in a “race to the bottom” — a race that destroys social and environmental values rather than promoting them.

When the game is over, we talk about why countries enter the race at all.

“Everybody needs jobs,” says Irene.

“If they don’t have money for their own factories, they’ve got to get it somewhere,” says Henry.

Those are the traditional answers. But our essential question was: Is there something in the rules that forces a competition to make things worse?

I explain the concept of “fiduciary responsibility.” Corporate executives, bankers, investment advisors, and many kinds of business people are responsible for managing the money invested by other people. Generally, this means increasing the “return on investment” by increasing profits. It means people who are rich enough to have disposable income to invest get richer. People who aren’t get their salaries squeezed.

“It’s the bottom line again,” says Mei Li.

“That’s why we won the game,” says Rob, whose country now allows child labor and pays starvation wages. “We cut their costs so they could make bigger profits.”

There are many reasons for poverty and ecological decline. As we reflect about what we learned from the Transnational Capital Auction, we talk about all the different ways people struggle to improve their lives. Political parties struggle for democracy against the temptation of corruption. Workers fight to organize unions. Teachers prepare students for more complex jobs.

But as business students, we are studying the financial rules that guide the entire game. I want the students to think critically about whether those rules are creating outcomes we truly desire.

National Accounting

The U.S. government uses a system of national accounting to measure the performance of our entire country. To understand this, I ask my students to visit the website of the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (www.bea.doc.gov). They download a table of numbers that shows the historical size of U.S. Gross Domestic Product (GDP), the dollar value of all goods and services produced in our country. Using graph paper or Excel spreadsheets, they create bar charts that show how GDP has skyrocketed during our lifetimes to $11 trillion per year. Government leaders, economics textbooks, media commentators, and many teachers agree that the growth of the GDP means our lives are getting better and often equate “growth” with “progress.”

A lesson called “What’s Up with GDP?” at the website of Facing the Future (www.facingthefuture.org) illustrates the distorted picture we get by equating success with higher production. Students role play as citizens of a make-believe town called Salmon Bay, Alaska. Facing the Future publishes an inexpensive curriculum guide called People and the Planet that includes instructions and materials for this activity and many others.

Most folks in Salmon Bay earn their living by fishing, but the town also has bankers, lawyers, business owners, retail workers, and the CEO of an oil company. Henry, the banker, passes out everyone’s monthly salaries in colored-paper $100 bills. We tape the bills together into chains — shorter ones for the fishing people and longer ones for the professionals and CEO. We use the total income of everyone in Salmon Bay to represent the town’s Gross Domestic Product.

Then disaster strikes. A truck hits the oil pipeline running through Salmon Bay, the oil spills, and a thin film flows over the waters of the bay. The fish die. The fishers lose their jobs. People get sick as oil contaminates the water supply.

But the spill boosts business for some companies.

Desiree reads an “after-spill” card from the curriculum guide that tells what happens, for example, to retail business owners:

We are sorry to say that some oil workers and fishers are out of work and are now spending less at the grocery store, movie theatres, and gas stations. However, the good news is that hotels and restaurants have been very busy since the spill, as there are many officials in town reviewing and monitoring the cleanup operations. We are experiencing a 50 percent increase in business. Doctors are busy. Lawyers are busy. The oil company CEO spends millions on cleanup, and gets a bonus for her performance.

After the oil spill, Henry adjusts pay envelopes for everyone in town. We again measure Salmon Bay’s GDP, represented by totaling everyone’s colored-paper $100 bills. Allan announces the bottom line:

“The GDP increased! “

This isn’t what the students expected. Because traditional GDP measures only economic transactions in dollars and cents but leaves out human suffering and environmental damage, the economy of Salmon Bay looks better after the oil spill.

As always, we remind ourselves of the essential question for this class: What can we see if we look at the lives of people behind the financial numbers? We would see the wrong picture if we used only dollars and cents to account for the success of life in Salmon Bay.

Next year I plan to use more lessons from Facing the Future. They recently published a useful student reading guide titled Global Issues & Sustainable Solutions that supports the People and the Planet curriculum. This set would help balance any business education curriculum.

Redefining Progress

Like full-cost accounting for companies, some economists support full-cost accounting for the national economy. If we want to account for the things that truly make our lives better, what important things could we measure?

After reading about labor struggles, watching videos about environmentally sustainable development, and role playing as economic decisionmakers, my students now can list dozens of important values: “job security,” “clean water,” “fair pay,” “health care,” “safe food,” “a sustainable future.” I scramble to list them all on the white board.

Then we visit the website of Redefining Progress (www.rprogress. org) and read about the Genuine Progress Indicator (GPI). GPI is an alternative to the Gross Domestic Product index. The students discover that it balances many of the “important values” they listed with more traditional economic indicators. For example, the GPI includes the value of unpaid childcare and housework. It subtracts, rather than adds, the expense of cleaning up pollution.

We print out a chart showing historical growth of the Genuine Product Indicator and lay it alongside our earlier charts of historical GDP. The traditional measure of U.S. economic success is increasing faster and faster. But when pollution, crime, natural resource exploitation, and other social and environmental factors are included, the Genuine Progress Indicator shows that our lives are improving more slowly.

I hope this lesson is a challenge to my business education students. It shows that there are alternative ways to measure social progress and well-being that could be used to help guide social decisionmaking.

The View from the Corner Office

My students are out of their seats again. They’re looking out the 40th-floor windows of a “Big Four” accounting firm, the local office of one of the world’s four predominant accounting companies. From this height they can see container ships from China unloading at the Port of Seattle. They can see the homeless shelter down the street from the King County jail. They can see the snow-capped Olympic Mountains 35 miles away across Puget Sound.

The young associate accountants who meet us are plugged-in and enthusiastic. Their clients are medium-sized businesses and large corporations. It’s a people-oriented profession, they say. Everyone has a laptop computer with wireless connection to their colleagues, plus links to accounting rules and tax laws in every country of the world. They love the variety, pay, and perks of their jobs. The best news is that Big Four firms often recruit business school students during their senior year of college.

Study accounting, pass the CPA exam, and you could start your career earning $30-40,000, with great upward potential, according to the American Institute of Certified Public Account-ants (AICPA).

Some of my students will find a place in corporate accounting. Some may start their own accounting practices and help small businesses or individuals. Many will use their knowledge of accounting principles to be informed investors and consumers — and perhaps activists. Whatever paths they choose, I hope they have the courage to ask the critical questions that lurk behind every financial decision: When we measure success in terms of dollars and cents, who do our decisions affect, and how?

Bibliography

Rethinking Globalization, edited by Bill Bigelow and Bob Peterson (Rethinking Schools, 2002).

Facing the Future: People and the Planet, Curriculum Guide, by Gilda Wheeler, John Goekler, Devin Hibbard, Diane Boyd, Mary Wondra, and Kim Bush (Facing the Future, 2002).

Global Issues & Sustainable Solutions: Population, Poverty, Consumption, Conflict, and the Environment, by Devin Hibbard, Gilda Wheeler, and Wendy Church (Facing the Future, 2004).

Redefining Progress: Genuine Progress Indicator, www.rprogress.org/projects/gpi

World Bank: Size of the Economy by Country, www.worldbank.org/data

Central Intelligence Agency: The World Fact Book, www.cia.gov/cia/publications/factbook

Clean Clothes Campaign, www.cleanclothes.org

Wal-Mart Watch, www.walmartwatch.com

Bureau of Economic Analysis: U.S. Economic Accounts, www.bea.gov

American Institute of Certified Public Accountants: Career Resources, www.aicpa.org

*All students’ names have been changed.