Singing Up Our Ancestors

Myrlin Hepworth’s poem “Ritchie Valens” is a Swiss army knife kind of poem, providing multiple functions—mentor text for poetic devices; biographic poem to help students praise family members, literary characters, or historical figures; tutor text that examines both racial and language discrimination in the United States; accessible model to launch students’ own poetry.

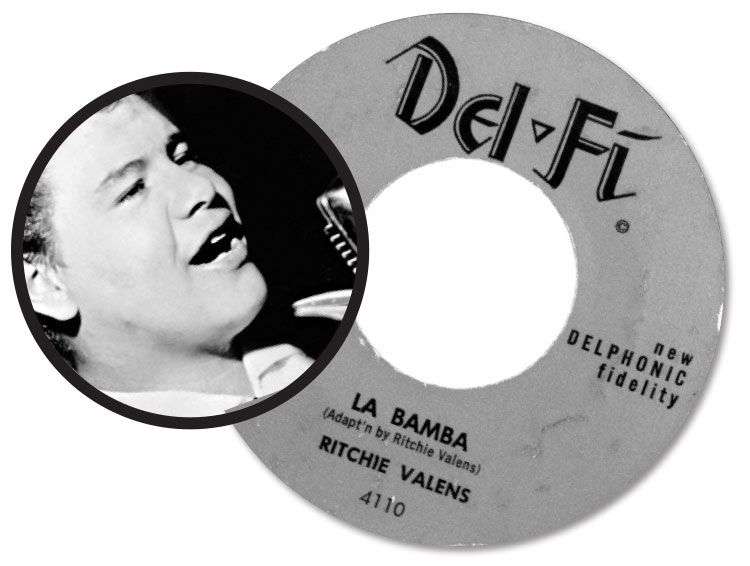

In the poem, Hepworth tells the story of Valens’ rise to fame, but also his brushes with racism because of his Mexican American heritage. Valens was born Richard Steven Valenzuela, but his producer at Del-Fi records shortened his name to give him “broader appeal”:

Richard Valenzuela,

they called you Ritchie.

Said Valenzuela

was too much for a gringo’s tongue.

Said it would taste bad in their mouths

if they said it,

so they cut your name in half to Valens,

and you swallowed that taste down,

stood tall like a Pachuco

and signed that contractpara su familia para su musica.

In eight months, Valens, who was 17, went from playing in local theaters in his hometown of Pacoima, California, to playing on Dick Clark’s American Bandstand. He wrote his own music and

Took an old folk song

from Veracruz,La Bamba,

Swung that Afro Mexican rhythm into rock and roll, “para bailar la bamba!”

Valens is considered the founder of Chicano Rock.

Hepworth, who is Mexican American and Anglo, works as a teaching artist in Arizona. His poem includes a line underscoring the linguistic racism that still exists 55 years after Valens’ plane tumbled from the sky into Clear Lake, Iowa:

Sang all Spanish lyrics at a time when speaking Spanish

came with a wooden paddle punishment.

In a line close to the end of the poem, Hepworth returns to the same theme:

And America is still trying

to shape you into Hollywood,

still trying to bleach the memory of your skin.

Wrote a movie and said you never spoke Spanish,

even though you understood each cariño your mother

placed into your ears as a child.

The movie chalked your death

up to superstition and Mexican hoopla.

Yes, Hepworth’s poem has it all. I’ve used the poem with freshmen through seniors (and adults) as a model, but it could be used with younger students as well. After my junior class studies the politics of language discrimination, they write biographic poems about literary and historical characters whose native tongues had been lost or severed. After reading August Wilson’s play Jitney, sophomores write poems about people they know whose lives have been disrupted by gentrification. During a break between units, seniors write about people in their own lives they want to praise.

Setting the Mood, Learning the History

When I teach the poem, I play Valens’ signature song, “La Bamba,” and project his image across a large screen as students walk in. Most students are familiar with the song, and some even sing along and dance as they move into their seats. “Hey, I watched that movie with my mom,” Trina remembers. “He’s the singer who died in a plane crash with Buddy Holly, right?” Vince asks. The “La Bamba”‘ upbeat rhythm is a great start to any day.

Once students settle into their desks, I tell them that we are going to watch a video clip of Hepworth performing a poem that we will use as a model for our own writing. “Hepworth is writing a poetic biography of a famous singer. You will also write a poetic biography. In this poem, Hepworth tells the story of Ritchie Valens, who sang ‘La Bamba.’ Notice how he tells the story. Think about what pieces of his story stand out for you.” (Of course, my introduction varies depending on the content—politics of language, Jitney, Civil Rights Movement, or personal writing. This introduction is for my juniors.)

Then we watch Hepworth’s amazing performance of “Ritchie Valens” (see Resources). Students fill the post-poetry silence with a variety of comments: “It’s a history.” “He talks about the night Valens died.” “He uses Spanish.”

Over the years, I’ve discovered that struggling readers often screech to a stop when they see words or phrases in another language. Usually, there is enough context in the reading to provide an understanding of the text. I use Hepworth’s poem to teach students how to push through their hesitancy to engage with the unfamiliar. “As you read the poem, you will come across words in Spanish. We will let the Spanish speakers in our midst help us, but first, I want you to try to figure out what Hepworth means in the line on your own. Guess. Write notes in the margin of your poem as you listen and read. Then we’ll come back and talk about it.”

I distribute copies of the poem and ask them to listen again as they read the text, but this time to look for the kinds of details Hepworth chooses. “What stands out about the story? What pieces of Valens’ history does he choose to tell?” After the second reading, students pull out more details. My juniors, fresh from their study of the politics of language, notice the part about shortening Valens’ name and about being paddled for speaking Spanish in school—two common practices used by colonialists throughout the world to discourage indigenous people from using their native languages. Most students also pick up on the “bleach the memory of your skin,” which leads to a discussion about how many artists—and people in general—have been forced to try to “become white”—assimilate into the dominant culture—in order to be “successful.” When students fail to notice these aspects, I point them out, because when they write their poems, I want them to remember how Hepworth handled historical information.

When we circle back to the words in Spanish, students realize that they can guess the words familia and musica because they look like family and music in English. The words they can’t figure out, like para bailar la bamba, they can understand well enough to continue reading for the gist of the poem. This is also a time for the Spanish speakers in our class to shine as they translate for us.

Raising the Bones of the Poem

At this point, I’m getting on students’ nerves, but we return to the poem again. “What are Hepworth’s poetic landmarks? What do you notice about how he moves the poem forward? What are his hooks?” Let me pause to say that these are questions I ask about almost every poem we examine—and about essays and narratives, as well. These are the “raise the bones” questions necessary to get students to read like writers. Instead of reading for information and content, at this point I want them to read to understand the poetic “moves” Hepworth makes to shape his poem. This, in turn, helps students learn to make those moves themselves—to learn from his style, but also to improvise or “lift off” from his poem as a model.

We travel through the poem, looking at information in each stanza. In the first stanza, for example, Hepworth has a hook:

You were the child

of R&B and Jump Blues

Flamenco Guitar and Mariachi.

This lead, “You were the child,” is a great way to open a poem, to introduce the reader to the person.

The second stanza tells more about the subject of the poem and what others said about them: “They called you . . .” Again, students can lift that line to fill out more details about their person. In the following stanzas, we notice incidents and obstacles that reveal more about Valens—little details like “playing a guitar with only two strings” and a neighbor helping “a left-handed boy playing a right-handed guitar.”

I point out the line “At 16 you were signed to Del-Fi Records” and suggest that it is a wonderful hook to tell another story and use their person’s age as a landmark. And, later in that stanza, we take note of Hepworth’s use of repetition:

But you did not have old blue eyes.

No, yours were young and brown,

brown like the dirt in the San Fernando Valley,

brown like the hands of your tios and tias

who worked in the fields for pennies,

died inside cantinas with broken hearts

Later we point out the historical references to the Zoot Suit Riots, to names of musicians—Chuck Berry and Bo Diddley—and places that Valens played. “Poetry resides in the specific,” I remind the students. “Give us details.”

Writing Our Poems

I tell students, “Ultimately, this is a love poem, a praise poem, a biographic poem, so think about who you want to write about.” In my junior class, students start with a list of people they studied in our language unit. In other classes, students have written about their family members, their personal heroes, or people from their cultural/racial background who deserve praise. My friend and colleague Gretchen Kraig-Turner, who teaches biology at Jefferson High School, asked students to write about scientists they’d studied.

We return to the “bones” of the poem, and I write some of the landmarks they noticed or I’ve pointed out on the board. “When you get stuck, return to Hepworth’s poem and notice how he moved his poem forward. I’ve listed some questions and leads to get you started”:

“You were the child of . . . “

“They called you . . . “

“At 16 you . . . “

What did people say about this person?

How did the person react?

What’s an incident you can tell about this person?

Did something happen at a significant age?

When you think of this person, do historical events arise?

What can we see? Hear? Watch on TV?

Student Poems

In our language pieces, Bridgette Lang wrote about Joe Suina, who is currently a professor at the University of Arizona. When he was 6, Suina was taken from his Cochiti Pueblo, an Indian reservation in New Mexico, to a Native American boarding school. Now Bridgette uses Hepworth’s opening line to start her poem:

You were the child of a thousand years of heritage,

Cochiti blood flowed through your veins,

Joseph Suina,

You were the child of pride and honor,

And you grew out of it.

Later, she uses Hepworth’s age hook to share more of Suina’s story:

So you turned 6 and went to school:

a classroom of white walls and white values.

You were so far from home that you forgot yourself, too.

You had to leave your Indian at home,

You had to forget your language,

Forget Cochiti, forget your Pueblo,

A beating ensued when you remembered.

Shabria Montgomery writes about Molly Craig, made famous in the movie Rabbit-Proof Fence, who was a mixed-race Aboriginal child stolen from her family in Australia and placed in a boarding school. Shabria lifts off from Hepworth’s line “You were the child of . . .” and creates a repeating line for her poem:

You are the daughter of love.

Ripped away from your mother

Forced to leave home.You are the daughter of the desert.

The rabbits running wild

The fence to keep them away.You are the daughter of color.

Light skinned but not light enough

Still forced to forget your home.

Hepworth’s poem encourages students to intersect with their own cultural, linguistic, and familial interests. Baqi Coles, a sophomore, writes about his great, great uncle Nat King Cole, who intrigued him, but he knew little about him. My time with Baqi’s class turned into a day of learning for me, too, as I watched students use their smart phones to find historical details for their poems. Baqi writes:

Nat, you were the child of rhythm,

destined to alter the course of jazz

with your classic vocal and piano style.They called you the King of Jazz,

the kind who held in his heart

the beat of drums inherited

from his African forefathers.The King who at 15,

dropped school to become

a jazz pianist full time.

You knew your destiny.

Sydney Broncheau Shimaoka, a student in Amy Wright’s junior class at Jefferson, explores her musical heritage by writing about Bruddah Israel Kamakawiwo’ole, a Hawai’ian singer and ukulele player:

Started as just a “kid with a ukulele”

to a young Hawai’ian man with native dreams

From the most sacred “Ni’ihau”

Slowly you became a legend,

Slowly you became an idol

Poems like Myrlin Hepworth’s “Ritchie Valens” help students see that poetry isn’t just about flowers and rainbows and unrequited love. It’s also about history, language, race, and resistance. Poets can use their voices and their space to sing up the past and to remember those who have gone before.

Resources

- Hepworth, Myrlin. “Ritchie Valens.” youtube.com/watch?v=AvVulbbm85s.

- Hepworth, Myrlin. “Ritchie Valens.”