Schools Should Not Prepare Students for Work

COMMENTARY A Forum for Reader Opinion

As I give speeches around the country, by far the most common buzz-phrase I hear these days is “school-to-work-transition,” a distressing indicator of the increasing corporate control of education (government long ago surrendered). I have concluded that this transition is a disaster in the making for schools.

Listen to what one employer, Alan Wurtzel, chairman of the board of the electronics discount firm Circuit City, says he is looking for: “In hiring new employees for our stores and warehouses, Circuit City is looking for people who are able to provide very high levels of customer service, who are honest, and who have a positive, enthusiastic, achievement-oriented work ethic.” What Wurtzel fails to say is that to people possessing these qualities, Circuit City offers its warehouse staff the minimum wage of $4.25 an hour while sales staff work strictly on commission.

The attitude of employers was well captured recently in a “Frank and Ernest” cartoon. A company personnel officer tells Frank and Ernest, “What we’re looking for is someone smart enough to pass our aptitude test and dumb enough to work for the pay we offer.”

The old saying, “The business of America is business,” has lately been rendered as, “The business of schools is business.” What has been lost in all the rhetoric is that schools have no business with business. They should not be preparing students for the world of work. That they are reveals a massive triumph of propaganda and conditioning that would make both Pavlov and B.F. Skinner beam. For three administrations, millions of young people have been kept out of the labor force in the name of keeping inflation low. That they are cynical should not surprise. That they have not risen up in revolt should.

We used to make fun of the Soviet Union and its “glorious worker” propaganda. But we glorify the concept of work just as propagandistically — just more subtly and more successfully (what we really glorify, of course, is capital). As John Kenneth Galbraith points out in The Culture of Contentment, we hide all jobs under the single glorious rubric of “work,” ignoring that much of “work” is ugly, hard, demeaning, and dangerous. Surveys have repeatedly found that most jobs are dull and boring with no intrinsic meaning. Should schools collude in the preparation of students to endure the boredom of meaningless, small, repetitive, dull, unhealthy tasks? I don’t think so. Most work is as nasty as it is unavoidable and we should realize that and treat it as such, not pretend it is something wonderful.

Consider the stunning popularity of the cartoon strip “Dilbert,” which is currently in 800 newspapers and is the fastest growing strip in the country. Dilbert is set in one of the most awful work settings imaginable. In one strip Dilbert proposes to a co-worker that they quit and set up their own business.

“Why quit?” asks the co-worker. “We can run our new company from our cubicles and get paid too.”

“Wouldn’t that be immoral?” Dilbert asks.

“That’s only an issue for people who aren’t already in hell,” the co-worker answers.

Since putting his Internet address on line three years ago, author Scott Adams has been besieged with letters asking, “How did you find out where I worked?” Apparently, a lot of people also think they’re already in hell.

The alliance between business and schools is itself an alliance made in hell. It calls for schools to perform a massive job of conditioning students to be docile. (Getting 42 million kids to show up at the same place — school — on time everyday is itself a mammoth achievement of docility training). To then claim that schools ought to be teaching students to be critical thinkers is ludicrous and hypocritical. The last thing an employer wants is someone who thinks critically. Critical thinkers would challenge the idiotic rules laid down by businesses.

In fact, schools have done a marvelous job on the supply side of the work force, but business and industry have done an absolutely lousy job on the demand side. And all the while, the productivity of the American worker, already the highest in the world, is rising. Although the United States is the low-cost producer of many goods and services, jobs are disappearing. At least, good jobs.

Manufacturing, where the good jobs are, lost 255,000 jobs in 1992. The restaurant industry alone added 249,000. Not many were for executive chefs.

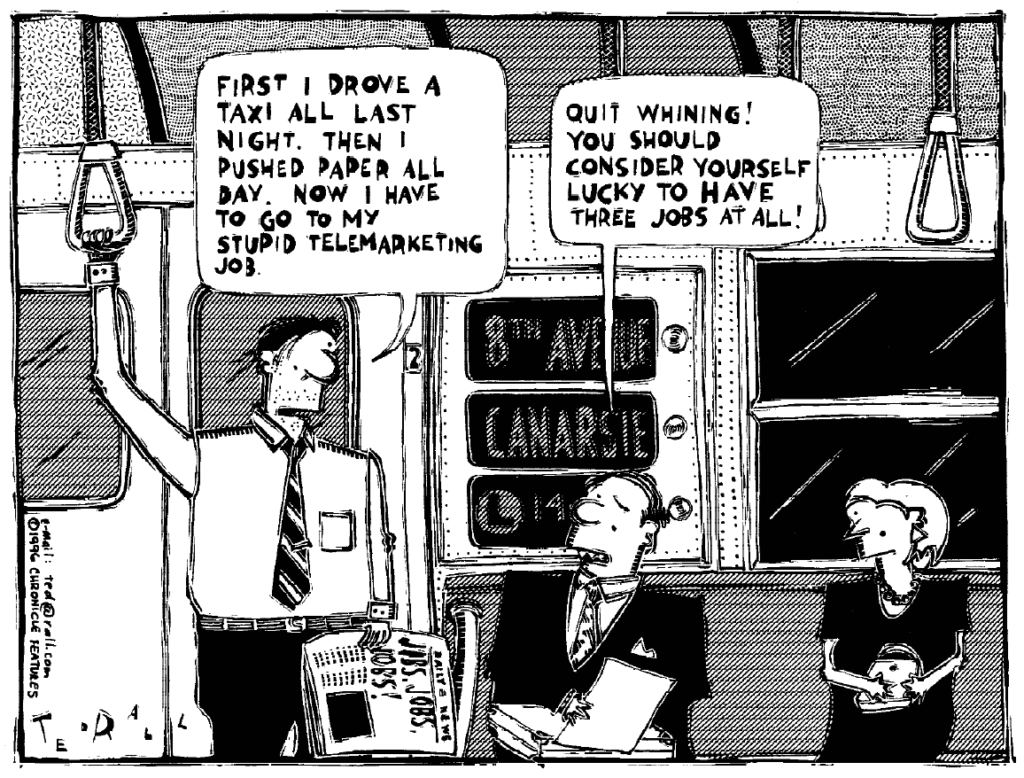

People were ecstatic this past March when the Department of Labor announced that 705,000 jobs had been created the month before, more new jobs than any month in over a decade. Yet most of the new jobs were in the service sector. A Jeff McNelly cartoon in The Chicago Tribune captured the situation well. He depicted an after-dinner speaker saying,

“The current economic recovery has produced 7.8 million jobs.” At the same time, the busboy clearing the table thinks to himself, “And I have three of them.”

An estimated 26-31% of our college graduates take jobs which require no college. One need not be a Marxist economist to view the call for the schools to raise students to ever higher levels of skill as a strategy to drive down the wages of skilled labor.

If the work of schools is not the world of work, what then?

How about a renewed emphasis on the school’s civic function? Thomas Jefferson saw education as the means of protecting us from our government: “In every government on earth is some trace of human weakness, some germ of corruption and degeneracy which cunning will discover, and wickedness insensibly open, cultivate, and improve. Every government degenerates when trusted to the rulers over the people alone. The people themselves therefore are its only safe depositories. And to rend even them safe, their minds must be improved somewhat.”

SCHOOLS’ CIVIC FUNCTION

For most of our history, schools concerned themselves primarily with this civic function. Surely Jefferson would be appalled at the corporate control of government, at our government-by-special interest, and our low voter turnouts. He would probably see them as failures of our educational system. Vocational concerns crept into schools only when the move began toward universal secondary education. As this movement really got underway, it coincided with the development of testing by such theoreticians — and zealots and racists — as Lewis Terman, H.H. Goddard, Arthur Otis, Robert Yerkes, Carl Campbell Brigham, and E.L. Thorndike. Looking at their bell curves, these psychometricians concluded that it would be inhumane to present the same curriculum to all students.

We are now in an era where another buzz phrase is “all children can learn to high standards” and ability grouping is out (in theory). What kind of education ought we to offer all children? Israel Sheffler defines education as “the formation of habits of judgment and the development of character, the elevation of standards, the facilitation of understanding, the development of taste and discrimination, the stimulation of curiosity and wondering, the fostering of style and a sense of beauty, the growth of a thirst for new ideas and visions of the yet unknown.” That sounds good to me — a liberal education, one that liberates. Schools should prepare children to live rich, generous lives in the hours that they are freed from work. They can be trained for jobs after they finish their education. This must be possible: as noted, study after study finds American workers the most productive in the world.

And what of vocational concerns? If high school graduates drift into college without knowing why, wouldn’t it be even more dangerous to let them drift into the job market where access to information is so much more difficult to come by? Well, yes. But why try to solve this problem during the high school years? Why not develop specialized centers that receive the students after they complete high school? Would it not be possible for vocational educators to provide much richer and more valuable information to students when they’re not competing with the rest of the high school for their attention? When they can have the kids all day long? Certainly, these kids are not needed by the market.

Seems reasonable to me. I’d be interested in knowing what the people in the trenches think.