School to Work: Problems and Potentials

When proponents of the School to Work program in the Milwaukee Public Schools cite success stories, John Holmes’ name often comes up.

Holmes, a teacher at John Marshall High School in MPS, oversees Eagle’s Wing Productions, a video production company staffed entirely by students. Under Holmes’ guidance, Marshall students have created professional-quality videos on gang violence, urban school safety, blindness prevention, and other important topics. A video on recycling, which the students produced for the S.C. Johnson Wax Co., has been distributed to thousands of schools and recycling programs nationwide.

Marshall is one of the 10 “first wave” schools that MPS, which serves more than 100,000 students in Wisconsin’s largest city, chose as pilots for School to Work during 1994-95, the program’s first year. A collection of profiles of the 10 pilot schools written for MPS lauds Eagle’s Wing for “showing kids the connections between what they learn in school and how these skills will transfer to the real world,” one of the School to Work program’s main objectives. A research report on School to Work’s first year, prepared by the prestigious California firm SRI International, singles out Eagle’s Wing for praise for providing “rich and rewarding workbased experience for students.” And district officials often mention Eagle’s Wing as an example of the kind of programs that should be spawned throughout the school district, in every school and at every grade level from K to 12, in order to meet the ambitious goals set for School to Work.

But take a closer look at Eagle’s Wing, and a couple of important and unsettling details about its connection to School to Work in MPS emerge.

First, the program has never received any funding, guidance or other support from the district’s School to Work program, and operates independently from the other School to Work activities now taking place at Marshall. Holmes developed Eagle’s Wing years before School to Work began, and keeps it afloat by writing grants to win outside funding. “We do a lot of School to Work type activities, but we’re out here plowing our own course, as it were,” he said. And second, Eagle’s Wing involves perhaps 50 students per year, at a school with a student population of more than 1,400. The program’s unique features, including its reliance on expensive high-tech equipment and intensive small-group work, would make it difficult or impossible to replicate on a larger scale.

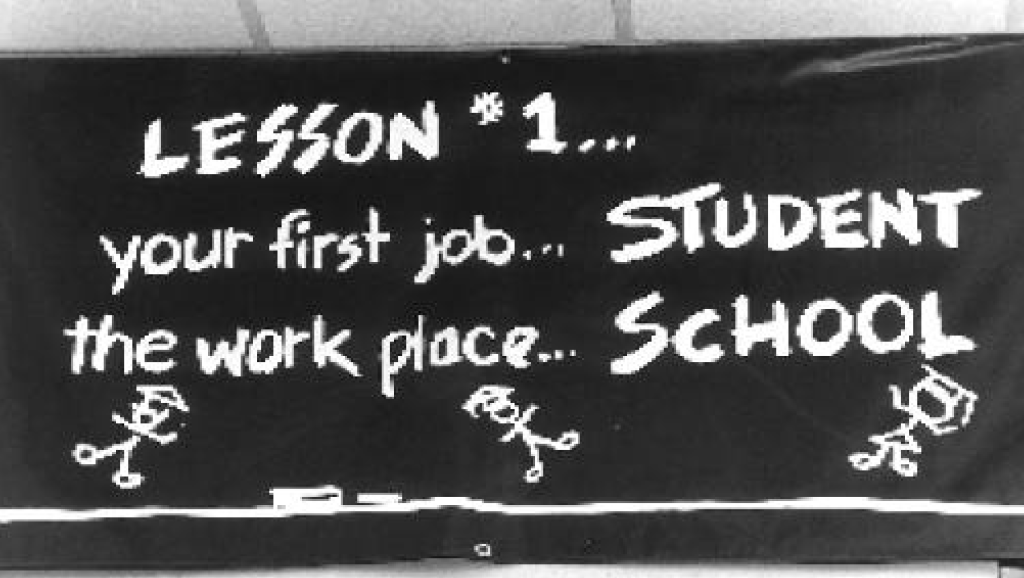

Marshall High’s other School to Work activities are by no means a waste of time, said principal Ann Griffiths. She gave the program high marks for providing new funding for staff development opportunities, and for creating “an obvious mandate for change” that has encouraged teachers and other staff members to “look at things differently and re-evaluate what we do.” Slowly, she said, more and more faculty members at Marshall are embracing a core tenet of School to Work: If schools are going to do a better job of preparing students to support themselves and to contribute to the world that awaits them beyond school, teaching and learning must change dramatically.

But Holmes’ experience illustrates some of the questions that teachers and administrators in MPS, as well as other observers, have raised about the district’s School to Work program. They wonder whether School to Work can really meet its goal of transforming teaching and learning throughout MPS, instead of merely showering a few more dollars, or a bit more publicity, on a few teachers who are already prepared to emulate the School to Work model. They wonder if the program will get the resources and support it will need, from the district’s leaders and the larger community, or if it will instead suffer the same fate as wellintended programs in the past that faded away after a few years.

Observers also wonder whether School to Work can stay true to its goal of putting high-quality student learning first, ahead of the interests of businesses taking part in the program, and whether it will adequately prepare students to protect their own interests in the workplace.

The MPS officials who run School to Work acknowledge that the program has encountered some problems and obstacles during its first two years. But they say School to Work is beginning to spread a new culture throughout the school district and the community. They say the program remains the best way to address the many daunting problems facing the district and its students.

ANAMBITIOUS AGENDA

Milwaukee’s public schools are plagued by many of the woes common to large, urban school districts today, including high dropout rates and low attendance. When School to Work was first being proposed in MPS, its proponents cited these grim statistics:

- During the 1992-93 school year, the high school attendance rate in MPS was only 79 percent.

- The overall high school grade point average was only 1.66.

- The annual high school dropout rate was 17.4 percent.

- More than a third of MPS students who entered high school in 1987 had dropped out before they were supposed to graduate in 1991.

Critics blamed the high dropout rates on school curriculum that failed to engage students, failed to challenge them to achieve to high standards, and failed to offer any tangible rewards for staying in school, such as knowledge, skills or training that would be applicable in daily life. Dropouts often find it next to impossible to earn a decent living in today’s rapidly shifting economy. As companies nationwide continue to export low-skill jobs to cheaper labor markets overseas, or to “downsize” in an effort to boost profits to stockholders, the days when a young man or woman could drop out of school and still find a good-paying job are fast becoming a distant memory. Milwaukee’s experience is depressingly typical of large Midwestern cities: The metropolitan area lost more than 51,000 manufacturing jobs between 1979 and 1987. New jobs were being created, but they tended to be concentrated in lowwage occupations.

Even when students do graduate, they often find it difficult to earn a living wage. More and more jobs that pay well require additional schooling, be it a degree from a four-year college or training from a trade or technical school. Yet half of all high school graduates nationwide do not continue on to college or any other post-secondary education.

School systems and educators nationwide have called for overhauling public schools to address these issues. Typical initiatives include revamping high school curriculums to make them more relevant to the “world of work,” and providing apprenticeships or job placements for at least some high school students as part of their academic experience.

The MPS School to Work program includes those elements, but goes much further. “MPS has a different perspective than many other school districts in this state and in this country,” said Peter McAvoy, a business consultant and a member of the task force created by thenSuperintendent Howard Fuller to map out the district’s School to Work plan. While it’s important to provide some students with apprenticeships or job training, “we wanted something beyond that, something that involves many more students.”

Simply put, School to Work in MPS is supposed to prepare students for success in college or in the world of work, by delivering high-quality instruction rooted both in sound teaching practices and the realities of the modern workplace.

The School to Work task force worked very hard at keeping School to Work focused on the needs of students, “and not making this a program to serve the needs of business first ,” said Tony Baez, an assistant professor at the Center for Urban Community Development at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee and another task force member. “Some of the people from the business community came in (to the task force meetings) with that agenda, but we worked hard to keep that from happening.”

In October 1993, the task force released a report calling for:

- The implementation of School to Work activities at all grade levels, from K-12. These could include student businesses, job shadowing, mentoring, partnerships, youth apprenticeships and job training. Activities should focus on helping students develop skills with broad applications, as opposed to specific skills suitable only for one type of employment.

- The creation of work-based opportunities for large numbers ofstudents guided by three goals: deeper learning, increased motivation, and the chance to seriously explore postsecondary education and work options.

- The development of a curriculum integrating the different academic disciplines and connecting those disciplines with work-based learning opportunities.

- The creation of teacher teams, with common planning periods and block scheduling opportunities, to support the development of integrated curriculum.

- The development of new tools for measuring student achievement in a more diverse and unorthodox education program.

The Milwaukee school district budgeted $2.7 million for the School to Work project for the 1994-95 school year. The district also received $1 million in state funding, and money from federal and private sources as well. Ten schools — three high schools, four middle schools and three elementary schools — were selected as “first wave” schools that year. The case of John Holmes and Marshall High shows that MPS officials, in their efforts to demonstrate the impact of School to Work’s first year, may have been too eager to give the program credit for activities and learning opportunities with roots that predate the program. Nevertheless, it’s instructive to look at the successes attributed to School to Work’s first year, because they illustrate the types of projects that School to Work officials hoped to see more schools develop. In addition to Holmes and Eagle’s Wing Productions, a district publication touted these first-year programs, among others:

- At Kosciuszko Middle School, students studied the principles of math and physics related to bridge construction, then toured local bridges with a city engineer. They also worked in teams to construct their own bridges, and held contests to see which designs could support the most weight.

- At the Thirty-Eighth Street Elementary School, teachers designed an entire curriculum around a large “peace mural” depicting famous peacemakers, which was painted at the school in the spring of 1994. Students researched the different figures who appear in the mural, wrote essays, participated in art projects and staged a “peace concert.” The highlight of the program came when South African Archbishop Desmond Tutu came to the school and signed the mural, right next to his likeness.

- Alexander Hamilton High School revamped its daily schedule into four 80minute blocks, and provided training for teachers on how to make the most of the new structure.

- Students at Custer High School “shadowed” volunteers from different professions as they perform their workday duties, in part “to learn the academic and social skills necessary” to perform those jobs. The students also reported to their teachers on the “academic aspects” of the jobs they observed, by explaining how math is used in that particular field, for example, or taking a social-studies perspective and making observations about age, gender and race in the visited workplace. In another of many School to Work activities at Custer, a manufacturing company invited teachers to tour its facilities and work in the various manufacturing jobs, to aid in developing related curriculums in math, business and marketing.

For 1995-96, MPS added 34 more schools to School to Work. The district budgeted $1.8 million, mostly for staff development activities such as half-day training sessions on integrating curriculum, building partnerships and other critical topics, said Eve Hall, the MPS School to Work coordinator. The district expects to implement School to Work in all schools by 1997, Hall said.

Asked whether School to Work is having an impact on the schools where it has begun, Hall said: “We’re moving. We’re beginning to see more of an ownership of the education of our children from business and our community partners. And more dialog is now taking place among teachers, administrators, and businesses on ways to work together, and on how to prepare children for the challenges that await them.”

The program’s emphases on integrated curriculum and team teaching are beginning to bear fruit as well, Hall said. “Teachers are saying, ‘Now I know the person down the hall.’”

Perhaps some teachers are saying that, but not all. Others say that scheduling hassles and a lack of training have hampered efforts to get teachers working together. At Milwaukee Trade and Technical High School, for example, most teachers assigned to teams do not yet share common planning periods, said Eileen Schwalbach, the school’s School to Work coordinator. “People have told me consistently that if you don’t have that common planning time, it’s not going to work.”

Teachers are indeed working together on integrated projects, she said, but many don’t know how to get started on the development of team teaching or integrated curriculum. “It takes time and knowledge to make teams work. Either we need money or we need someone with that knowledge to help us.”

Tech has received federal money to support the development of one teacher team, “but that’s just one small program that affects fewer than 100 students,” all of them 9th graders, Schwalbach said.

Despite these difficulties, Tech has a small core of teachers who readily embrace School to Work, Schwalbach said. But getting the message to reach beyond that core, to translate into very different attitudes that are broadly held in a school, is difficult. “When I think how far away we are, I get discouraged,” Schwalbach said. “Then I have to re-assess and see how far we’ve come.”

Other teachers and school-level administrators echoed Schwalbach’s experience: they said a core of teachers committed to School to Work had taken root in their schools, but getting the larger faculty community to embrace the School to Work message was problematic.

Part of that intransigence is simply human nature, said Andrea Loss, a former English teacher at Custer High School in MPS. Many teachers “close the door of the classroom and they are the king or queen,” she said. “A lot of teachers just don’t want to let go” of that security and control.

Ambitious programs like School to Work also can get bogged down in large schools, where the complexities of the scheduling and resource distribution have put the brakes on many innovative ideas. Loss remembered when her 10th-grade students at Custer were not offered the chance to take a foreign language that year, because of scheduling conflicts between language classes and vocational classes. “They were expected to wait until they were juniors,” she said. “Nobody would say they were trying to track those kids, but you can see how it can work that way.” The experience of Loss’ 10th-graders is especially disturbing because many colleges and universities require several years of foreign-language study in high school as an admission requirement.

Further, Loss questioned whether MPS teachers are getting adequate support to engage in truly transformative change. A teacher who wanted to explore integrated curriculum, for example, might need to go back to school and earn additional certifications, an expensive and timeconsuming process for a teacher who must foot his or her own tuition bill and hold down a full-time job while studying. What’s more, in a typical large high school, a principal in charge of overseeing 90 teachers “won’t be able to offer much beyond superficial suggestions” when a teacher comes looking for help with a problem, Loss said.

PROBLEMS WITH SCALING UP

This year Loss left Custer, which served 1,200 students, to help launch a new school called Metro High School, which will have a maximum of 330 students. She’s hopeful that the smaller school will provide opportunities for working closely with students that aren’t possible in a typical large high school.

Indeed, school size and class size appear to be critical factors in the development of School to Work, which calls for much tailoring of curriculum to the needs and opportunities that come before each student. Getting 40 students out of 1,500 involved in a meaningful program is one thing; finding ways to duplicate that experience for the rest is another.

Another MPS program that is separate from School to Work, but seems to share many of its goals, is the New School for Community Service. Up to 100 students in 11th and 12th grade, students from all across the Milwaukee area work closely with six teachers to develop high-quality learning experiences around work opportunities. Students work at various jobs, in such places as investment companies and computeraided design firms, while completing their regular academic requirements. They can earn academic credit for work experience, depending on the number of hours worked and how well they meet the learning objectives laid out in a plan written together by the teachers, job providers, and the student. “We’re kind of writing a mini-curriculum around each placement opportunity,” said Marty Horning, a teacher and coordinator at the New School.

Size, or rather the lack of it, is critical to the success of the New School program, Horning said. Every student must be responsible enough to set his or her own schedule and then follow it, juggling the requirements of classwork and job placements. Students are interviewed individually, along with a parent or guardian, “to make sure we get people in this school who are ready for that much commitment,” he said. “They need to be able to get around, to function and flourish in an adult environment, and be willing and able to take charge of their own education.”

“A larger, random sample (of students) would be less mature,” Horning said. “Many would be unable to meet the higher expectations and responsibilities of a program like this.”

New School faculty also must find the placement opportunities for each student, a process Horning described as “the result of a lot of pure legwork.” If such a program were greatly expanded, it would be difficult to find enough quality placements to go around, he said. Already, School to Work representatives “are knocking on a lot of doors around town looking for opportunities for their students, and finding that we’re already there,” he said.

It’s also going to take awhile to change the attitudes of MPS staff members, Horning said, who have seen reforms come and go before. “I think right now you have a certain amount of cynicism that this is another one of those initiatives that will last as long as the money holds out, and then it’ll be gone. So at this point I don’t know how fundamentally it’s having an impact on content and methodology.”

Larry Miller, who works with Loss on the Metro High project (and is also an associate editor of RethinkingSchools), said he hasn’t seen any widespread changes in teacher practice or student experience due to School to Work. “It’s going to be very slow in coming,” he said. “It’s hard to break down the old system, old ways of doing things.”

Miller also said he is skeptical about the role School to Work will play in teaching students “to be able to evaluate and criticize their employers when necessary…. To me, School to Work means more than just finding a kid a job. We have to teach our kids that they need to fight against discrimination and bad working conditions. We have to educate them to the fact that when they get to the workplace, they are going to have to struggle. School to Work is not doing that.”

Eve Hall, the MPS School-to-work coordinator, acknowledged that the School to Work program does not include any formal emphasis on preparing students for workplace struggles over unsafe work conditions, low pay, job security, and other labor issues. “We do, however, stress that students should develop the skills and abilities they will need to deal with the real world,” she said.

Hall also agreed that Milwaukee’s economy has fallen on harder times in recent years, making it harder for students to find good jobs. “But that just makes me more determined,” she said.

“We have to give students some transferable skills, so they aren’t locked in to any one type of employment.”

A 1974 graduate of Milwaukee’s Juneau High School, she returned to the city after attending college in Florida and working there for a number of years. “I remember when this city was bustling and people were working,” she said. “And I came back and saw people just standing around…. Are we preparing students to make the changes and choices that are mandated by that kind of shifting?”

Hall didn’t shrink from acknowledging many of the problems with School to Work cited by teachers and administrators, including a lack of common planning time for many teacher teams, tight budgets, and the problems inherent in scaling-up such an ambitious program. When told of Andrea Loss’ 10th-graders at Custer High being denied a chance to take a foreign language because of scheduling hassles, she shook her head. “Hopefully that’s the exception and not the rule,” she said.

But Hall said she remains 100 % committed to the School to Work project. “I know it’s not easy,” Hall said. “There are lots of obstacles, issues, challenges. But the rewards will exceed the pain we have to go through to make it work. And we are making it work.”

“We’d like to see students with options when they graduate from high school,” Hall said. Students should be able “to transform the world we live in, not just live in it. School to Work seems to me to be the best way to make that happen, to make education everybody’s business. I don’t know of a better way to bring all the stakeholders together.”

As School to Work develops, and the various stakeholders—including teachers, administrators, students, parents and the business community—sort out their different expectations and plans for the program, many eyes will be focused on them. Milwaukee’s School to Work program has attracted considerable national attention from educators, politicians and citizens who will be watching to see whether a large, urban school district really can succeed in making the widespread, transformative changes in the way students learn and the way schools connect with the community.