Reviews

FILM

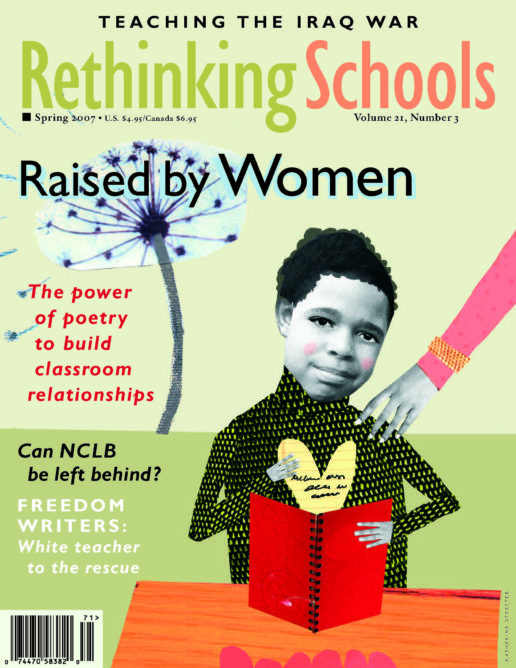

White Teacher to the Rescue

A review of Freedom Writers

I find it hard to put a finger on what bothers me about Hollywood’s teacher movies. Is it the young white teachers saving kids of color? Is it the guilt I feel as a teacher who may not have succeeded as well as these superheroes? Is it the notion that teachers should be mother, father, college counselor, and best friend to our students, despite the incredible personal toll that takes? Or is it the movies’ individualized solutions to structural problems?

It’s all of that—and more. I want a teacher movie where there aren’t card- board heroes and villains (except Bush and the NCLB gang) but there is a genuine analysis of how race and class play out in schools.

For now, however, we have Freedom Writers. Released in January, the movie is based on the book The Freedom Writers Diary and chronicles the educational triumph of Erin Gruwell, an idealistic young white teacher who inspired the hearts and minds of her remedial Asian, black, and Latino students in her freshman English class. (Gruwell left classroom teaching after about five years and now heads a foundation promoting her “Freedom Writers” approach.)

Starring Hilary Swank as Gruwell, the film opens with footage of the violence following the 1992 Rodney King verdict in Los Angeles—setting the scene for the tension at the Long Beach school system here Gruwell teaches, which had recently been forcibly inte- grated.

The story truly begins when, during class, a Latino student draws a racist caricature of a black student and passes it around. Our hero, “Ms. G,” snatches the paper from the desk of the black student depicted in the drawing. The student is crying. Ms. G angrily asserts that the picture reminds her of caricatures of Jews in the years leading to the Holocaust. (Why it only reminds her of anti-Semitic caricatures and not of other racist caricatures of African- Americans, I can’t tell you.) At the end of her speech, she asks the students how many of them have heard of the Holocaust. Only one—the white student—has. She then asks how many students have been shot at. Slowly, each student raises his or her hand (except for the same white kid).

It’s a turning point. For Ms. G, there’s the realization of the violence that haunts her students’ lives. The students, meanwhile, begin to “connect” with Ms. G. They become involved, they read The Diary of Anne Frank and relate it to their lives, and they organize to stay with their teacher for the next academic year and beyond.

‘Connecting’ with Students

Early in the film, Ms. G uses a 2Pac song to introduce “standard” poetic devices. The frustrated youths roll their eyes at their teacher’s ignorance of hip hop, and the lesson is a failure. Later, the students’ study of the Holocaust success- fully connects, in part because of Ms. G’s passion about the issue. Which raises several questions. Rather than studying their own histories—U.S. slavery, the violence of colonization and border creation, the Khmer Rouge regime in Cambodia—the students study the Holocaust. Even when the stories of

students of color are brought into the classroom, they can rarely be a focus, a stand- alone issue. We teach hip hop lessons so that students can learn Shakespeare. Even where the Holocaust is a vehicle for the students telling their own stories, that connection to a white experience is key. The Holocaust should be studied in its own right—but so should the current lived experiences of youth of color in the U.S.

The movie’s turning point, in which Gruwell realizes the extent of violence in her students’ lives, is significant only because she didn’t realize it before. She doesn’t come from where her students come from, and she apparently hadn’t learned much about their lives before she began teaching.

There is something deeply worth- while about Ms. G attempting to con- nect the oppression of her own people to the oppression experienced by her students. But the theme of white legitimization of the experiences of youth of color is one that runs throughout Freedom

Writers, and it often precludes the kind of grappling with racism that—just once—I would like to see on screen.

Individualistic ‘Solutions’

The problem with Freedom Writers isn’t so much the kind of cookie-cutter stereotyping that we see in Hollywood’s white-teacher-as-savior genre. Rather, it’s the highly individualistic nature of these stereotypes. It scares me that people will leave this film thinking, “See? You can change the system.”

Sure. If, like Ms. G, you get two other jobs, neglect your personal life, isolate yourself from your fellow teachers, and rely on your white privilege to insure you won’t be fired. And, by the way, that’s not changing the system. It’s changing one classroom. Don’t get me wrong—changing one classroom is an accomplishment. And as far as I can tell, Gruwell and her former students are doing their best, through their foundation, to make this story bigger than what happened in room Room 203. But let’s be clear: This is not a movie about the depth and breadth of racism in education; it’s a movie about a white savior.

There are undeniably “saviors” of color, as well as students “saving” themselves. They just don’t get movies made about them.

Taking Race Seriously

People of color talking about racism is nothing new. And too often, when we rail against moments in which the specter of race remains invisible to white perception, white people think we’re delusional. Racism can only be taken seriously, it seems, when it is championed by white allies, or by young people of color who can’t quite be held responsible for their plight.

There is a marked absence of black and Latino adults in Freedom Writers, and there’s a reason. They aren’t youthful enough to elicit sympathy. Though the audience is supposed to pity Ms. G’s students, we are not supposed to sympathize with their parents—an incarcerated father, a mother who kicks out her son. The parents’ struggles, and the ways in which their lives are also held down by structures of race and class, are not part of the story.

There’s no room in Freedom Writers for a bigger narrative. We can’t talk about adults of color “saving” themselves from racism, because that’s just called living your life. We can’t talk about a teacher of

color “saving” her students because, apparently, it’s only exciting to watch white people suddenly become aware of race and start a crusade. And we can’t begin to talk about what it would take to save anybody from the “tangle of pathologies” that is structural racism. That would have meant, in addition to Ms. G’s students finding a way to tell their stories, they would also have had to demand resources for their class so Ms. G wouldn’t have to work three jobs—to say nothing of challenging the tracking system, organizing student forums to discuss

the impact of the integrated school district on their lives—and on and on. Who wants to sit through a movie that long?

Watch Freedom Writers. Enjoy it for what it is. But afterwards, take away the message of continuing to struggle against racism in education. Don’t be fooled into thinking the short-lived triumph of one savior in one classroom is enough.