Preview of Article:

Reinventing Schools That Keep Teachers in Teaching

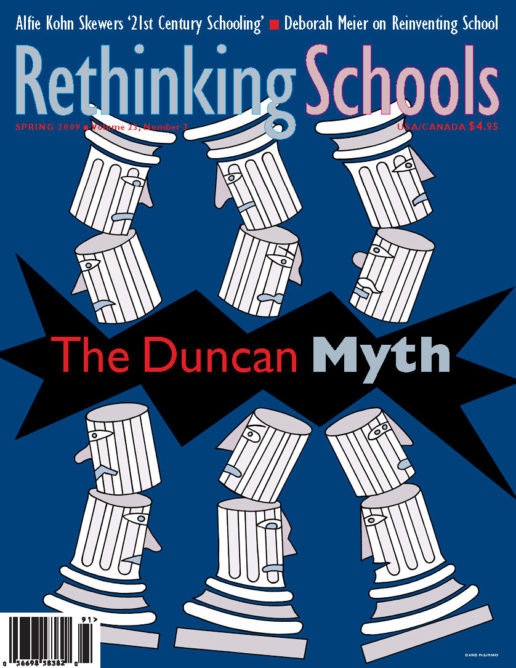

Illustrator: Rob Dunlavey

Editors’ Note: This essay is another in a series of Ford Foundation-supported articles and essays focusing on retaining and nurturing teachers. Your comments and anecdotes are welcome. Please address them to Fred McKissack at jsokolower@earthlink.net.

If we want teachers who are smart, caring, alive to students’ needs, and are in it for the long haul, we need to consider how to create schools that are themselves centers for the continual learning of everyone connected to them. We’ve learned most of what we know about teaching K-12 from our own schooling experience. Unlearning powerful past history in the absence of equally powerful settings for relearning won’t work.

We can’t ignore the likelihood that few would-be teachers are themselves “well-educated” when they walk in the door—on subject matter or on teaching/learning. But the school setting is a gold mine for doing something about it in the very process of educating the young. So it was for me when I began teaching in the early 1960s, and so it was for the schools I helped found, in the 1970s, ’80s, and ’90s. Universities can assist in this process, as can every other educational agency we can lay our hands on. But the schools are the center of where it must take place. Because in that way it does double or triple duty—it educates kids, their teachers, and their families all at the same time. Whether young teachers improve and whether they remain in the profession depends in large part on the character of the schools they find themselves in.

The startling reality for me was that even in an average inner-city kindergarten in Chicago in the 1960s, I found more intellectual stimulation than I had experienced in graduate school. No doubt, my previous education helped me to sort out what I was observing, but kindergarten teaching did so by involving me in ways that no school before had. It did so by adopting exactly the opposite message than the current style of standards-heavy reforms propose.