Racism, Xenophobia, and the Election

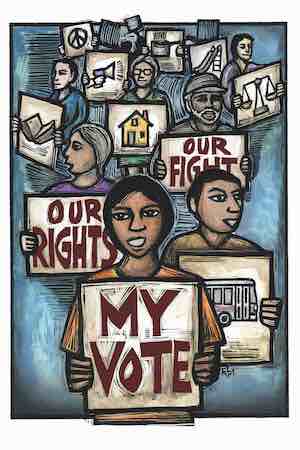

Illustrator: Ricardo Levins Morales

As teachers and students return to classrooms this fall, together we have to try to make sense of a tumultuous presidential campaign and a summer of racial violence that have forcefully surfaced the racism that plagues our nation.

Elementary and middle school students have grown up with an African American as president of the United States. This is a historic milestone. But these same students have also grown up in a nation that’s increasingly unequal, a country where police killed more Black people in 2015 than were lynched during the worst year of Jim Crow.

In the past several months, students have watched Donald Trump use racist, Islamophobic, misogynist, and anti-immigrant vitriol to whip up a terrifying level of support, with ominous repercussions no matter who wins the election.

Even as Black Lives Matter has spearheaded a growing movement against police violence, our children have been subjected to an unending stream of police murders of Black and Brown people, including the recent videos of the murders of Alton Sterling and Philando Castile.

Michelle Alexander, author of The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, wrote after watching those videos: “We all know, deep down, that something more is required of us now. This truth is difficult to face because it’s inconvenient and deeply unsettling. And yet silence isn’t an option.”

We hope that teachers will view these disturbing developments not as issues too controversial to talk about, but rather as teachable moments to address white supremacy and our nation’s rich history of movements for justice and equality.

In these scary times, the courageous undocumented youth of the Dreamers, the Movement for Black Lives (a collective of more than 50 organizations, including the Black Lives Matter Network), and thousands of other activists are providing light and hope. Powerful teaching confronts the dangers squarely and also builds on their examples and those of other young people standing up for justice. When a student put up a “Build a Wall” banner in Forest Grove High School in Oregon, many students were outraged. The next day hundreds of them walked out in protest; as word spread through social media, students from seven other area high schools joined in. High school and college students in nearby Portland staged their own protest march later that week.

White fans at a high school girls’ soccer game in Elkhorn, Wisconsin, started chanting “Trump, build that wall” at the predominantly Black and Latina Beloit Memorial team. A few days later, the neighboring Evansville girls soccer team posted a video condemning the racist incident and expressing support for the Beloit team. At Beloit’s Big Eight Conference game against Janesville Craig, players from both teams stood side by side during pregame introductions as a show of solidarity against racism.

Trump and Our Classrooms

The “curriculum” of the presidential campaign inevitably finds its way into our schools and classrooms. As we reported in our summer issue, a study by the Southern Poverty Law Center found that the campaign is “producing an alarming level of fear and anxiety among children of color and inflaming racial and ethnic tensions . . . [and] an increase in bullying, harassment, and intimidation of students whose races, religions, or nationalities have been the verbal targets of candidates on the campaign trail.”

Trump’s ascendancy parallels the growth of extreme right-wing parties throughout much of Europe, where a toxic stew of austerity, economic anxiety, and the refugee crisis has fueled xenophobic and neo-fascist rallies, electoral victories, and violence.

His popularity also reflects the growth of racism and inequality in the United States, which has been exacerbated by policies pursued by both the Republican and Democratic parties. Internationally, pro-war policies have led to unspeakable suffering, wasted hundreds of billions of dollars, fostered terrorism, and destabilized whole swaths of the planet. Bipartisan “free trade” policies have thrown people out of work in the United States at the same time they have increased inequality abroad. Domestically the “war on drugs,” “three strikes,” zero-tolerance discipline policies, and other criminal justice “reforms” have led to unprecedented rates of mass incarceration of African Americans.

At the same time, we have witnessed an inspiring resurgence of demands for an end to police violence, for racial justice, for climate justice, for gender justice, for economic justice, for immigration justice. There’s a lot to talk about.

The polarization and racism of this election season make it especially important to create safe classrooms where students engage deeply in critical analysis. Of course, a student who is a member of a targeted group should never be singled out as a “spokesperson.” And perhaps it’s time to rethink traditional approaches to teaching about elections.

For example, many teachers routinely hold debates with students representing candidates from different parties (more than just the Democratic and Republican parties, we hope). However, this year such debates might be counterproductive. We don’t want to create classroom forums where students-as-candidates could repeat racist rants, nor should students be subjected to them. Slogans like “build that wall” are essentially racist slurs; “jail the bitch” is a sexist slur.

A better curricular route might be to look at the premises underlying key campaign issues—immigration from Mexico, for example—by asking questions: What is the history of the border between the United States and Mexico? How have initiatives like the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) affected Mexican farmers and workers, and influenced immigration from Mexico? Who benefits and who is hurt—on both sides of the border—by “free trade?” (See “Who’s Stealing Our Jobs?”, and the Rethinking Schools book The Line Between Us: Teaching About the Border and Mexican Immigration.) After this kind of study, students can more easily recognize a slogan like “build that wall” for the ignorant and hateful demagoguery that it is.

Instead of limiting classroom conversations to the issues as the campaigns define them, teachers can draw on the perspectives of activists who call into question the narrow two-party discourse and offer rich critiques of the racism, xenophobia, sexism, and Islamophobia heard on the campaign trail—and sometimes at school. (See “As a Teacher and a Daughter: The Impact of Islamophobia,” by Nassim Elbardouh, summer 2016.) This is the perfect time to invite local community and campus activists into our classrooms.

The issue of voter suppression is particularly relevant this election. President Obama’s election eight years ago and the changing demographics of the United States motivated Republican legislators and a conservative Supreme Court to roll back historic victories of the Civil Rights Movement. Teaching about the campaigns for the right to vote—for women, people of color, residents of Washington, DC, or Puerto Rico—exposes the racism and sexism endemic in our nation’s history, as well as the ongoing struggle to turn the United States into a democracy. It also opens up discussions about who can and can’t vote today, why it’s important to vote if you can, and ways to make your voice heard if you can’t.

What is particularly powerful are stories—from the past and from today—about youth working together against racism and other forms of oppression. Resources abound: children’s picture books, young adult novels, short stories, poetry, videos. Check out the archives for Rethinking Schools magazine, our books, and the Zinn Education Project for ideas. Anti-racist teaching is important in all subject areas, not just social studies. Math classes can tackle the racial inequality of the criminal justice system, language arts classes can address gentrification, science classes can focus on environmental justice (see “Lead Poisoning: Bringing Social Justice to Chemistry,” by Karen Zaccor).

And then there’s action beyond the classroom walls. In addition to powerful examples like those of the students in Wisconsin and Oregon, teachers in North Carolina demonstrated at a Clinton rally where Obama was scheduled to speak. They demanded an end to deportations and that Clinton and Obama do everything in their power to release detained refugee youth.

Progressive school board members in various cities are promoting systematic approaches to fighting racism. In Milwaukee, despite objections by right-wing talk show hosts, the school board passed a Black Lives Matter resolution and put nearly half a million dollars in this year’s budget to fund implementation. In San Francisco, Albuquerque, Portland, Oregon, and other communities, educators, students, parents, and community activists have come together to fight racism through similar initiatives, such as ethnic studies programs. Many of these draw inspiration from Tucson, Arizona’s hugely successful Mexican American Studies program, outlawed in 2010 by conservative lawmakers. These are the kind of long-term, institutional responses that educators, students, and community members are fighting for.

We need to seize on teachable moments to address racism and white supremacy during this election cycle and, after that, continue and increase our efforts. From the dinner table to the classroom, from staff meetings to school boards, educators need to find ways to put the issue of race and racism front and center and keep it there.

We know time is short before the elections, but the damage wrought by racist comments and slurs fueled by the campaign will be long-lasting. And the anti-racist teaching that emerges because of thoughtful parents and educators—and from students who demand more relevant curricula—will flower and bear fruit long after November’s election.