Precious Knowledge: Teaching Solidarity with Tucson

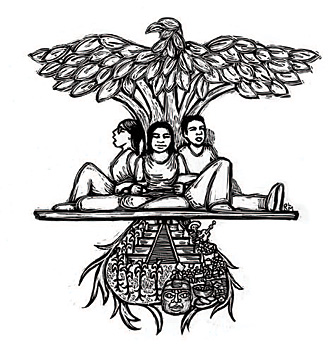

Illustrator: Ricardo Levins Morales

The class huddled around my laptop. Their efforts to be silent made the anticipation palpable. We had been invited to speak on NPR’s Call-In Radio and the broadcast was under way. Omar and Diana, elected to be our spokespeople, sat together on the other side of the room, waiting to be brought on the air to discuss HB 2281, Arizona’s controversial ethnic studies ban. Talking points had been discussed and collectively decided upon.

“This is perfect timing,” the radio host said, “because Devin Carberry is calling in right now. Devin is a teacher at ARISE high school over in Oakland and is calling in with his class. Devin, how are you talking about this with your students?”

“Good morning,” I answered, tensing at the awkward 15-second delay before we heard my voice coming out of a laptop speaker. “I am trying to cultivate my students as leaders, so I’m going to pass the phone to them.”

Omar picked up the phone and introduced himself. “We are really engaged by this topic because we see what’s happening in Arizona is wrong—that they are going into schools and taking away people’s history.”

“What was your reaction?” the host asked.

“I was shocked. They are treating books and knowledge like weapons by confiscating them from students and suspending classes having to do with Mexican American Studies.”

Omar passed the phone to Diana, who was visibly nervous. “It reminds me of the movie Walkout. History is repeating itself. Back then they didn’t let Latino students use the bathrooms or speak Spanish in their classrooms. The banning of books made me mad because they are obviously trying to . . . hide the truth that for 500 years we have been oppressed. I feel like it’s time to fight back.”

The host thanked us for joining the show, we logged off, and the students applauded. Then, energized, we went back to our study of the attack on Tucson’s Mexican American Studies (MAS) program.

“Our Education Is Under Attack!”

Although the physical distance is great, there is a thin membrane of cultural and ideological distance between Oakland and Tucson. Ninety-five percent of my students are Latina/o, mostly first generation, mostly Mexican. Our charter school is located in the heart of the Fruitvale District of Oakland, a largely Latina/o barrio with a history of community organizing.

While I anchored my junior/senior humanities class on contemporary social movements in skill development, critical analysis, and assessment, I included students in the process of deciding which movements to study. For each topic we discussed, we considered what would foster growth while keeping students engaged. We had decided to begin with the Zapatistas in the context of Mexican history but, before long, current events burst into the classroom as events in Tucson heated up.

I showed the class a film clip of youth taking over a Tucson Unified School Board (TUSD) meeting—chaining themselves to the chairs of school board members. They were fighting to defend the MAS program in the district, which Arizona’s HB 2281 had targeted the previous spring. The dramatic imagery of students pushing past security guards and police, while unfurling the chains hidden beneath their shirts, was a definite conversation starter. And when we watched the video of Tucson youth chanting “Our education is under attack. What do we do? Fight back!” my students were provoked and full of questions: What happened to the arrested students? What if students weren’t documented? Did the TUSD School Board still cancel the MAS program? I asked if this was something we wanted to investigate further. The response of my class was a resounding yes.

We began with some background reading. Our school uses a “five levels of critical analysis” framework across classes and subject areas:

- Explicit: what is being directly said or done

- Implicit: the message behind the statement or action

- Interpretive: connection to yourself and your surroundings

- Theoretical: what theoretical concepts apply and how they help explain the issues (e.g., white supremacy, capitalism)

- Applied: what course of actions you are going to take once you have acquired this knowledge

Using this framework, I prepared two articles for them to read about the Tucson ethnic studies debacle: one on the passage of HB 2281 and one on the impact on the MAS program. I provided additional background information myself since I was involved in Arizona local and state educational politics during my five-year stint attending college and then teaching there from 2003 to 2008.

I created three columns on the board: explicit, implicit, and interpretive. As we read the articles together, students wrote facts and important quotes in the explicit section, including the percent of TUSD’s budget that would be withheld if the MAS program continued, quotes from Arizona State Superintendent of Schools John Huppenthal and Attorney General Tom Horne, and key components of HB 2281.

In the implicit section students wrote what they thought were the implications of the information in the explicit column. For instance, they saw the withholding of funds as a tactic to turn the rest of the district against MAS.

In the interpretive column, they wrote their personal reactions to the articles. Joaquin observed that books were being treated like contraband: “Does that mean that the school can search you for those books . . . as if you were carrying a weapon?” That implies, he went on, that “knowledge is a weapon. It’s no wonder they want to shut down MAS.”

Precious Knowledge

Once we knew the broad strokes, I screened the film Precious Knowledge, a powerful documentary on the history and impact of the MAS program in Tucson, and the struggle to defend it. I distributed a graphic organizer with two columns on one side—Explicit and Implicit—and a larger square on the back for Interpretive. The explicit column was for important quotes, facts, laws, and characters in the documentary. The implicit section asked students to read between the lines of each of the explicit column entries—examining the intent of the director, the underlying message, and the larger context. The interpretive section was homework. Students were asked to reflect on their personal reactions to the movie as well as draw connections to other texts, their own lives, and other coursework.

As we watched, I paused the video after the first few scenes to ask what they had written in the explicit section. The students focused on the establishment of MAS as a continuation of the walkouts that happened in Tucson decades prior. Then I asked, “So what are the implications of those facts? Why did Tucson educators feel the need to create MAS?”

Edgar responded: “The United States makes Latinos believe that their culture isn’t important or needed. It’s as if Latinos had nothing to do with the development of the United States. Students don’t learn to appreciate their culture’s struggles, therefore they follow the system’s expectations, which involves dropping out. They begin to work for the rich class and stay poor.”

Janeth added: “Without our history there really isn’t an us.”

Other students talked about the absence of ethnic studies in their previous schooling and how refreshing it was to learn about nonwhite people upon their arrival at ARISE.

At the next pause, students noted central facts about HB 2281. “It basically makes ethnic studies illegal in Arizona,” one student volunteered.

“What is the implication?” I probed. “Why would the state of Arizona want to pass a law banning ethnic studies?”

“Tom Horne is disallowing students from learning about their own Raza because he is afraid those students would take action based on their knowledge of their past history and present oppression,” answered Janeth.

“So why are they doing this?” I asked. “What do you think their motivations are?”

Diana responded that Arizona politicians are afraid that students learning about oppression “would direct anger toward the government. People like Tom Horne are afraid of being overthrown. But it’s not about that; it’s about the right to learn about your own culture. They must fear that too, though. It’s like Frederick Douglass said: A slave is no longer a slave after gaining knowledge about himself. I think it’s that and, like we’ve talked about, it’s divide and conquer.”

“I don’t get what you mean,” I said.

“They are trying to keep us divided and uneducated so we won’t fight for what’s ours,” Diana continued. “They want us to just stay Americanized and whitewashed. They benefit when we don’t know ourselves and our purpose, when we are divided as a community. The classes in Tucson teach people to unite.”

For homework, Edgar wrote in the interpretive section: “Ethnic studies wasn’t just any class for students, it inspired them to succeed in high school so they can go into college and further on. Students learned what society expects them to do as they grow, so they decided to stay in school and prove society wrong—that not all people of color end up being criminals or janitors.”

To follow up on the film and readings, we held a Socratic seminar based on these questions:

- Why is ethnic studies important?

- What theories help us explain the ban on ethnic studies?

- How should we apply our knowledge?

On a graphic organizer, each question had three corresponding boxes:

- What is my opinion?

- What evidence supports this opinion?

- What questions do I have related to this question?

Students spent an hour working individually and in small groups to review and develop their ideas.

When the Socratic discussion began, students were charged with indignation that the majority of their teachers prior to high school had failed to teach them about their own history. Amabel mentioned her involvement in a Raza education program that started in 6th grade, and how it helped her to develop a positive self-identity grounded in the historical context of her ancestors. I pushed back: If ethnic studies is such a necessity, and worth fighting for, then why is it many of you don’t do your homework related to ethnic studies, don’t show up to school on time, cut class, and are resistant to reading outside of class? No one had an answer, but for many, this unit was the most engaged they had been in class.

Talking to UNIDOS

Whenever possible, I like to arrange for people to speak with my class who are directly involved with the topic of study. In this case, I already had connections in Tucson, so it wasn’t difficult to arrange a Skype date with Elisa Meza, a University of Arizona student and alumna of MAS who works with UNIDOS, the youth-led grassroots organization fighting against HB 2281. To prep for the interview, we filled out a KWL chart reviewing what we knew already, creating questions about what we wanted to know and, after the discussion with Elisa, filling in what we had learned.

With Elisa projected onto the screen and all my students huddled around my webcam, we spoke for nearly an hour. Elisa painted a vivid picture of the political climate in Arizona and updated us on UNIDOS’ organizing efforts. She described their strategy: garner local and national community support to oppose HB 2281 through direct action, protest, and litigation. In addition, UNIDOS was working to continue ethnic studies outside of school. Someone had donated a small house to UNIDOS, which they were using as their headquarters as well as a space to continue ethnic studies classes. My students were impressed by the level of commitment and organization of UNIDOS, a group run by people approximately their age. They wanted to help.

“What can we do?” they asked Elisa. She asked us to educate our community about the struggle in Arizona. She also asked us to take a photo demonstrating our solidarity, one that would alert Arizona politicians to growing national anger at the attack on the MAS program.

Martina reflected in her journal afterwards: “Today’s experience has been amazing. I am thankful we were able to speak with people who are being affected by other people’s bad choices. Those choices affect us even though we are miles away. It is our Raza and we can help them out and show them our support by sending them books that they are not able to access in school anymore. We can also help them spread the word and call for attention and support towards them.”

In response to Elisa’s request for solidarity, students decided to use our all-school weekly meeting for an informational skit depicting students watching banned books packed up and taken from their classes. Five students volunteered to plan and act in the skit, while others created a banner that read “Tucson: You hella shady!” We took an all-school photo in front of the banner. Our photo went out across social media and was included in UNIDOS’ newsletter.

Then we got an even better opportunity to help spread the word. We were invited to the Bay Area Urban Schools Student Leadership Conference at Berkeley High School, and the students were asked to present workshops.

Students separated into two groups based on the topic they were most passionate about; one group chose Tucson. The Tucson group began by outlining what they thought was the most important content to convey. Students excavated all the materials I’d given them and reviewed their notes. Once the outlines were made, they delegated responsibility for pieces of the presentation to one another. Diana described the process:

If someone had more notes about one part or more understanding about one part of what was going on in Arizona, we let that person plan that part. We started by dividing the lesson. We knew we needed to explain this, this, and this, so we asked: What do you know how to explain the best? We assigned it accordingly and then had one person put it together as a PowerPoint presentation. Whoever created a slide for the PowerPoint also taught it.

As I watched from the sidelines, it didn’t seem like they needed much help. I interjected occasionally to help them see where they might need to better develop connections and background knowledge; otherwise I gave them space. Once the slideshow was finished, I encouraged them to practice it.

Each One, Teach One

We were unaware until we got to Berkeley High that we would be the only high school students presenting. I reminded my suddenly nervous students that they were prepared, that youth love youth presenters, and when they first heard about Tucson they were thirsty to learn more.

Once the first group of students had settled into their chairs, Amabel asked if they had heard about the banning of ethnic studies. There were a few nods and a young woman from Berkeley High summarized HB 2281. Then they asked all the students to join them in reciting the poem In Lak ’Ech, which we had begun reciting every morning after watching Tucson students do the same in Precious Knowledge. Diana explained more about HB 2281, followed by Janeth, who read excerpts from the law. Next, Edgar talked about the key proponents of the law. Kevin introduced the Precious Knowledge trailer.

After the trailer, Roxanna asked students: “How do you relate to the movie?”

One student said: “I can identify with what the students are talking about because this is the first year I’ve taken an African American class. . . . The Europeans asserted their greatness and that’s what you learn about in ‘U.S. history’, but all of us are U.S. history. We are forced to learn about Caucasian people who did these great things but seldom do we learn about ourselves, so then our image of ourselves isn’t the best. I don’t see myself in history books, in these people.”

Everyone applauded. Roxanna then asked: “What would you do to fight against it if they passed a similar law in California?” The participants discussed occupying schools, boycotting “American History,” walking out, and distributing fliers. A young man offered: “Before a bill like that passes we should try to promote other cultures to sort of show how cool some things are, passing knowledge, so that you don’t have to take [an ethnic studies] class to know about it.” A young woman suggested that all the students at the conference should come together again to help Tucson and help themselves. Another student asked, “What did Tucson say they want us to do?” In unison four of my students said: “Inform others.”

At the end of the workshop, the participants joined together for a photo to send to UNIDOS.

The next day we reflected on what worked and what needed improvement. Everyone agreed that the workshops were a success. Diana thought that her group should have more explicitly used the five levels of analysis. “[The participants] could have used the five levels to see what’s behind things, and not just for what we are teaching; they can apply it other aspects of life and the world.”

A couple of weeks after the workshops, we were invited back to Berkeley High School to screen Precious Knowledge and facilitate break-out conversations with 175 students, mostly students learning English. Janeth reflected later: “The students were very engaged . . . because they are all from different ethnicities and understand completely how the students in Arizona feel about their history being taken away from them.”

Each year, we hold an exhibition night for families during the last week of school. My students wanted to teach their parents about HB 2281 and ask them what sort of Raza education they wanted for their children. The conversation was electric. Parents talked about the contradiction that their children wanting ethnic studies in school, but they never asked their parents about their family history. Parents also praised the school for integrating ethnic studies into our curriculum, since many of them never had such opportunities. The conversation caused me to lament the fact that I had not involved parents more during the semester. We should have invited them in as teachers, experts, and participants.

Diana, in her reflection on the course, said: “I gained a lot of skills, especially in learning how to teach what we had learned. It was able to get stuck in our heads that way. . . . We all felt motivated because it was something we chose to learn about and that affected our community.”

Resources

- Billeaud, Jacques. “Arizona Schools’ Ethnic Studies Program Ruled Illegal,” Associated Press, Dec. 27, 2011.

- Rodriguez, Luis J. “Arizona’s Attack on Chicano History and Culture Is Against Everyone,” Huffington Post, Jan. 18, 2012.

- Precious Knowledge, A Dos Vatos Production, 2012. www.preciousknowledgefilm.com