The Power of Words

Top-down mandates masquerade as social justice reforms

Illustrator: David McLimans

Really what this [school reform] is about is equity and social justice,” a district official told a local newspaper reporter when a new curricular change called anchor assignments was introduced to Portland Public Schools teachers in fall 2005. “It doesn’t matter what school you’re at, what ZIP code you live in, you should have the same opportunities for a rigorous instructional program like every other student in the city.”

Sounds good, right? But what was the school reform? Multicultural books embedded into thematic historical units? Time for teachers to meet and construct lessons for students that integrated math, science, social studies, and literacy around a contemporary issue like immigration, global warming, or the war in Iraq? No. The school reform was an order from the superintendent that every teacher at a particular grade level give the same assignment to every student. She called them “anchor assignments.” These assignments announced to teachers that equity, justice, and rigor were located in a standardized curriculum that all teachers were expected to administer.

As the director of the Oregon Writing Project and as a classroom teacher for over 30 years who attempts to work for justice and equity, I was dismayed at the appropriation of social justice language for a top-down mandate that disenfranchised students and teachers. But this is not a phenomenon unique to Portland, Ore. As I travel around the country, I’ve discovered that central office administrators more and more frequently steal the language and metaphors of social justice education to push their top-down agendas.

First, let me take a moment to challenge the idea that these anchor assignments had anything to do with equity, justice, and rigor. In language arts classes starting in the 3rd grade, every student was required to write a literary analysis essay. The assignments privilege essay writing as the only genre worth teaching. As one consultant said in an elementary workshop, “The days of children lying on the carpet writing their little stories are over.”

District administrators distributed anchor assignments as stand-alone work. These assignments, without benefit of instruction in the craft of writing a specific genre like literary analysis, ignored the fact that all students do not start with the same skills; some need more background knowledge in order to succeed on the task. The creators of the anchors (which teachers dubbed “anger assignments”) assumed that students learn from dropped-in assignments created in a vacuum. District administrators, evidently unfamiliar with the actual terrain of teaching writing, failed to understand that it’s not the writing of an assignment that teaches students to write; it’s learning how to write that improves student writing. Students learn when assignments are embedded in a rich curriculum, when they have grappled with big concepts in their lives and the lives of historical and fictional characters, so they can write out of a well of experience that they have rehearsed through talk and example and examination of the genre.

Equity? Well, I suppose that, regardless of ZIP code, every student will now have access to the same insipid anchor assignment.

Unfortunately, Portland is not the only place where district administrators hijack the language of the Civil Rights or social justice education movements to push districtwide mandates as quick fixes to complex problems. Of course, it’s the desperate need for radical education reform that lends credence to the faux democratic prescriptions of the language hijackers. One reason the rhetoric is compelling is that it boldly states the truth: Poor students and students of color have been historically disenfranchised and underserved by schools across the country. And some of the reforms are right on: for example, open access to honors classes for all students and funding effective in-school intervention for students who are falling behind.

Standardization Does Not Mean Equity

But the majority of the reforms, like Portland’s ill-conceived anchor assignments, equate “equity” with standardization. For many districts, that translates into common curriculum, common pacing guides, and common assessments. Depending on the district, this standardization may include common textbooks with pacing guides that dictate day-by-day lessons as well as regularly scheduled common assessments that keep teachers and students goose-stepping in line to the end of the year.

As the Oakland Unified School District’s “Equity Plan” states, “To ensure consistency and equity across schools, the district must put in place pacing guides and syllabi that tailor textbook adoptions to Oakland’s needs and students. In addition, mandatory expectations for daily language arts and math instruction must be adopted and monitored through classroom observation, again addressing the wide variability of exposure to standards-based instruction that has historically occurred.”

Translation: Because they’ve made such a mess out of things up to now, teachers cannot be trusted to imagine, create, or enact curricular reform. Change will come from on high. The school managers will choose materials, decide how they will be taught, and will monitor compliance. Ultimately, these changes made in the name of “social justice” lead to the deskilling of teachers.

My colleague, Mark Hansen, co-director of the Oregon Writing Project and extraordinary 4th-grade teacher, told me a story that illustrates how the domination of the textbook keeps teachers from seeing themselves as creators of curriculum. Mark is featured in an Annenberg Teaching and Learning video. The clip shows Mark and his students walking through his school’s low-income, immigrant neighborhood in North Portland. Students carry small notebooks and gather ideas for a persuasive letter about their concerns: lack of traffic signals which make it dangerous for them to cross the street, mean dogs on the block, a malfunctioning tire swing. Mark’s lesson is a great example of creating an authentic writing lesson situated in students’ lives. The assignment has purpose, audience, and a real aim for students to see themselves as both writers and actors in their communities. On two different occasions teachers from other states asked him what writing program he used to get such good writing out of his students — an indication of the widespread adoption of scripted curricula. As Mark said, “I was stunned. Teaching was reduced to a consumer choice.”

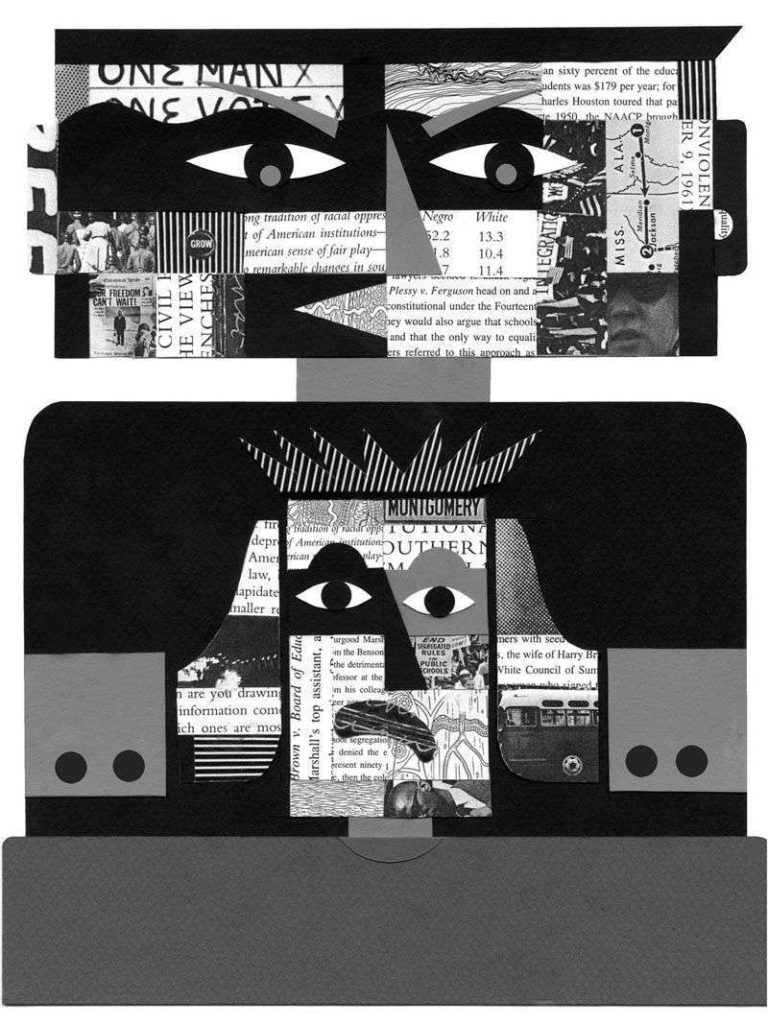

Despite the theft of language from one of the most profoundly democratic movements in American history, these new educational reforms are rooted not in our country’s Civil Rights Movement, but in the managerial strategies popularized by Frederick Winslow Taylor and made famous in Charlie Chaplin’s dystopian film, Modern Times. This is the classic in which Chaplin plays a factory worker whose every motion managers script and pace in such excruciating detail that he goes berserk and ends up being carted off to the insane asylum. In his discussion of corporations’ adoption of scientific management and its impact on workers, Harry Braverman wrote: “[A] belief in the original stupidity of the worker is a necessity for management; otherwise it would have to admit that it is engaged in the wholesale enterprise of prizing and fostering stupidity.” Substitute teacher for worker and administration for management.

If school districts wanted to embrace a real Civil Rights agenda instead of the rhetoric of the movement, then they might turn to the work of Ella Baker, Septima Clark, Bob Moses, Charles Cobb, Myles Horton and others involved in organizing the Freedom Schools in Mississippi and the Citizenship Schools throughout the South. Like Mark Hansen, these organizers believed in situating the literacy lessons in the lives of the local people, drawing on their students’ interests and questions and using those materials as the basis of their lessons. As Charles Payne wrote in I’ve Got the Light of Freedom: The Organizing Tradition and the Mississippi Freedom Struggle, “The teaching style developed by Robinson and Clark emphasized ‘big’ ideas — citizenship, democracy, the powers of elected officials. The curriculum stressed what was interesting and familiar and important to students, and it changed in accordance to the desires of students.”

These civil rights organizers/teachers saw literacy as a tool for raising people’s consciousness about the race and class divisions that needed to be changed in our society. Literacy was not taught in isolation from the context of the learners like the current paced, scripted curriculum guides that encourage the belief that all students need the same lesson on the same day. If our contemporary schools are concerned about “teaching for equity,” they might ask students who come from historically oppressed communities to analyze their own experiences in the ways these organizations encouraged. For example, in a memo to the Mississippi Freedom School teachers, the organizers wrote, “The purpose of the Freedom Schools is to provide an educational experience for students which will make it possible for them to challenge the myths of our society, to perceive more clearly its realities, and to find alternatives, and ultimately, new directions for action” (B_08_MemoToFSTeachers.htm). Clearly, the kind of teaching for equity employed during the Civil Rights Movement did not advocate using the same curriculum with pacing guides and tests for students. Instead of the current method of deskilling teachers by purchasing curriculum, Myles Horton’s workshops at Highlander brought local leaders together to share experiences and strategies — in much the same way that the National Writing Project does in the intensive summer institutes. According to Horton: “We debunk the leadership role of going back and telling people and providing thinking for them. We aren’t into that. We’re into people who can help other people develop and provide educational leadership and ideas, but at the same time, bring people along.”

Channel Ella Baker and Septima Clark: Talk Back

As teachers, we need to decode the rhetoric and talk back to school districts that speak of equity and social justice, but treat us like robots that deliver education programs designed and shipped from sites outside of our classrooms.

Teachers in Portland challenged both the language and the implementation of the proposed reforms masquerading as movements for equity and rigor. Because high school language arts teachers were the first to experience the sting of anchor assignments, they led the charge against them. Teachers across the district came together and wrote a response to the anchor assignment mandate:

As language arts teachers, we disagree with the anchor assignments. This is an example of a top-down decision that was made without any discussion with language arts teachers across the district…. We want to make it clear that while we oppose the imposition of the anchor assignments in our classes, we are not opposed to teaching writing. We want to clarify the difference. We don’t assign writing, we teach it. In fact, our daily work consists of teaching literary analysis, narrative and persuasive writing, but this work is developed through the study of a work of fiction or nonfiction that builds towards the essay or narrative piece.

Teachers also disputed Superintendent Vicki Phillips’ description of these mandates as a move towards “equity”; they addressed her word choice directly:

We agree that equity is an issue, but we would like to challenge your version of it. For the past six years, language arts teachers at every high school have tackled the issue of equity in much deeper, systemic ways. We untracked our freshmen classes, so that students from diverse cultural, racial, and social economic backgrounds have an opportunity to learn together and to see themselves as capable of entering honors classrooms…. When we untracked our classes, we also challenged ourselves to learn new methods of teaching that would reach the diverse members of our classes…. Those of us who have been successful in teaching untracked classes also taught each other strategies.

When teachers across the district critiqued this “social justice reform” and wrote letters stating that they would not implement anchor assignments because they were poorly constructed, they were threatened with insubordination. The same people who claimed to work for “equity,” sought to suppress discussion and critique.

Elementary teachers in Portland Public Schools also fought back. At community hearings and board meetings, teachers across the district testified against a fast-tracked curriculum adoption. In a petition, teachers embraced the equity impulse of securing more materials for poorly supplied schools, but rejected the equation of equity with sameness:

The adoption process of literacy “core curriculum” materials at the elementary level needs to be slowed down and thoughtfully re-examined. Many of our schools do need new materials; they have for some time. However, purchasing and implementing a single set of materials across the entire district, on such a tight time line, without seriously examining the materials our schools already use with great success is an expensive gamble. We need to assess what is and is not working in individual schools. Then we can build on our strengths to remedy any weaknesses. That is how we will see real lasting improvements for all Portland students.

The teachers cited research that contradicted the district’s assertions that common textbooks would lead to equity for all students:

- No research shows that purchasing a new reading program reliably raises reading achievement (Berends, Bodilly, & Kirby, 2002).

- Building teacher capacity and supporting rigorous teacher communities ( e.g., study groups, teacher research) is the key factor for student achievement (Allington, Cunningham, 2006).

- Scripted curriculum deskills teachers, reducing them to deliverers of content rather than synthesizers of complex ideas (NCTE).

- The programs presented as possible adoptions do not align with the philosophies and rigorous teaching practices of many PPS schools.

- No single program can meet the needs of a large and diverse district like Portland.

- Portland’s reading achievement has consistently risen without a district-wide adoption.

Portland teachers did not stop the anchor assignments, which the district renamed “common assignments,” but teachers now collectively write them and worked over the summer months to embed them in curriculum units. They also collectively designed teaching strategies to avoid the stand-alone nature of the original mandates.

And elementary teachers, who found ardent allies in the college literacy community, did not derail the curriculum adoption, but one courageous school board member added an amendment to every adoption. As the Board notes read: “Board Director Dilafruz Williams won unanimous approval from the School Board for an amendment to each adoption. The amendment confirms and emphasizes that the school district will continue to encourage creativity in teaching and learning, with teachers able to choose additional materials for their classrooms to supplement the district-provided materials.”

In these times, when even the historic civil rights case Brown v Board of Education has been reversed, teachers cannot afford to stand on the sidelines of curricular debates wringing our hands while district leaders speak in social justice sound bites and impose cookie-cutter curriculum reforms that deskill teachers, disempower local communities, and rob our students of a real social justice education. We may not win the battles, but our words and actions must demonstrate that education is contested terrain that we are willing to fight for.

Resources

Braverman, Harry. Labor and Monopoly Capital: The Degradation of Work in the Twentieth Century. New York: Monthly Review, 1974.

Emery, Kathy, Sylvia Braselmann and Linda Reid Gold. Mississippi Freedom School Curriculum. (http://www.educationanddemocracy.org/

FSCfiles/B_08_MemoToFSTeachers.htm)

Payne, Charles. I’ve Got the Light of Freedom: The Organizing Tradition and the Mississippi Freedom Struggle. Columbia and Princeton: University of California Press: Berkeley, 1995.

SNCC, The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee Papers, 1959-1972 (Sanford, NC: Microfilming Corporation of America, 1982) Reel 67, File 340, Page 1183. Reprinted with permission of the King Library and Archives, The Martin Luther King Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change, Atlanta, GA.