Opening Pandora’s Box

An Interview with Oakland School Board Member Toni Cook

Toni Cook has served on the Oakland School Board since 1990. It was Cook who prodded her fellow trustees on the board to unanimously support the nation’s first education policy recognizing Ebonics as the “primary language” of many students, comparing their language needs with those of immigrant children.

In this interview Cook tells how she came to be at the center of a national debate about language, race, and the education of African-American children.

Cook was interviewed by Nanette Asimov of the San Francisco Chronicle. The interview originally appeared Jan. 19, 1997.

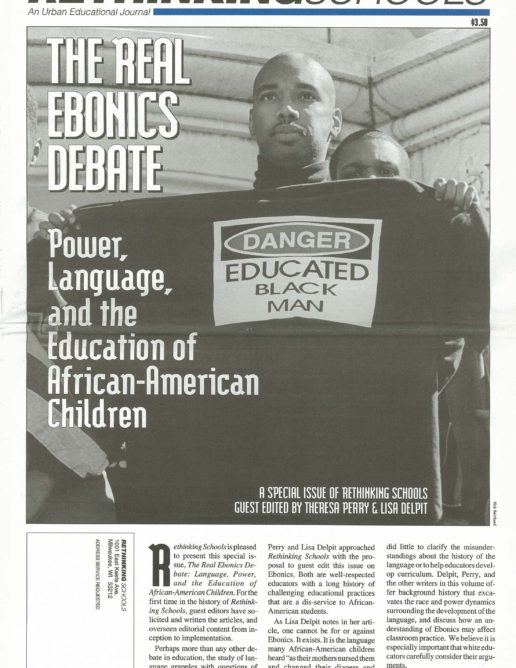

Rep. Maxine Waters, (D-CA) center, poses with Carolyn Getridge, then superintendent of the Oakland schools, left, and Toni Cook, board member, prior to their testifying on Capitol Hill on Jan. 23, 1997.

Other than making a lot of people mad, what have you done here?

I’ve sounded a bell that everyone is talking about. We got a call from Amsterdam and another one from South Africa. I’m finding that more people are becoming anywhere from supportive to understanding about this.

Has anyone given you serious trouble?

Someone called from a radio talk show and played real raw, racist stuff live and on air. My reaction to the first flood of phone calls (on my answering machine) was to deep-six every call.

Why?

I was broadsided by the controversy. I didn’t get home (from the board meeting) until 2 a.m. and I didn’t listen to any news the next day because I didn’t think anything we did was newsworthy. I’m just thinking, “I can’t function.” So I get up and make the call (to my job at the San Francisco Housing Authority): “I’m not coming.” Then Edgar, our board’s assistant, calls and says, “Can you come over?” I said, “Edgar, I’m trying to put a lie together about why I’m not going to work.” He said, “All hell has broken loose on the resolution.” I said, “What resolution?” He said, “The one put out by the African-American task force. The mayor’s on a rampage.”

Why was (Mayor) Elihu Harris so mad?

I used to work for Elihu. He could be mad at anything! And when I got there, he had already gone off to (Superintendent) Carolyn Getridge. And he asked me, “Do you know what you have done? I’m getting calls from everybody in the world! This is embarrassing to Oakland! You all have adopted a policy that’s going to teach Black English!”

I said, “Elihu, I know you’re cheap, but do you have television? Did you watch the school board meeting last night? We meant you no ill will in terms of your challenges with this city. But our kids are being ridiculed if they speak Standard English—“Ugh, you talk like a white girl!” So this is the problem we’re faced with, and this is how we’re going to deal with it.” Elihu kind of calmed down a little and we began to focus on why we did it like we did.

What did you do and why did you do it?

I asked the superintendent to form a task force to look at the performance of African-American kids. Since I’ve been on the board, dropout rates, suspensions, expulsions, truancy — all have gone up for African-American kids. But enrollment in the gifted and talented program and presence in college-bound, honors, and advanced-placement classes were not proportionate to Black enrollment, which is 53%.

What about special education?

Of 5,000 kids in that, 71% are African-American. And they were in there for “causing disruption.”

Aren’t special education classes supposed to be for students who are disabled or have learning disabilities?

Yes. And you have to have a referral to be placed in the program. The referrals disproportionately were because of a “language deficiency.”

What’s that?

When you really dug down, it’s that they weren’t writing or speaking Standard English. We found there were white and Black teachers making referrals. And white and Black principals — disproportionately Black — saying yes. So when the task force began to talk with teachers, it was like, “well, we don’t have any strategies for these kids.” The only one they had was the (state’s) Standard English Proficiency Program fora few teachers who got the training.

So what did you do?

You know, there’s an old guy who comes to the board meetings named Oscar Wright. He came to every board meeting until his wife died about a year ago. And he would stand with those trembling hands and talk about the performance of African-American kids — test scores, truancy — and he said, “I see having four Black board members has made no difference in what these kids are doing.”

And we hung our heads, because it was true! We had a crisis situation and we kept coming up with old ways. Or ways that were so homogenized they didn’t really wake anybody up.

You’re saying that test scores will go up as African-American students begin speaking Standard English?

Yes. Which ultimately means — more critically — that they can go from high school to college if that’s their choice. You can no longer drop your kid off in kindergarten and expect to pick him up in the 12th grade with a diploma that means he’s ready for college. We should quit making these promises that we’re going to do that by adding health programs, and all those other kinds of things. That is not about education. I know they need all that, but there isn’t any education strategy here. When it’s directed to African-American kids, it’s basically the assumption that we have to control them before we can educate them.

You don’t feel that way?

No.

How can you teach a kid who’s out of control — whether threatening a teacher or just making noise?

Teachers need the teaching and learning tools to know how to communicate with these youngsters to capture their attention. We have some kids with a proven record of suspension in the third grade, and they’re going like this (waves wildly) in the math class! I’ve seen that at some of our schools in the deepest parts of the flatlands.

Are you saying their teachers caught their attention because they spoke Ebonics?

What they knew was how to hear the child, listen to the child, correct the child, and make the child feel good about being corrected. These are teachers who have been through our Standard English Proficiency Program.

Give me an example.

Well, I go to classes to read to the kids. Everybody knows Dr. Seuss, so I made the presumption that I could read a page and the child would read a page. I found two things: Either the kids could not read, or they could read, but the words they pronounced were definitely not on that piece of paper.

What were they saying?

-ing’s left off of words, consonants left off words, and you begin to think: “Does this kid have dyslexia? Half the word is falling off.” And then I went to Prescott Elementary, and I noticed that in (teacher) Carrie Secret’s class, where most of the kids are from the housing projects, they could read, and tell you what they had read, had great diction, good reasoning skills. And this was the third grade.

You’re saying that the kids in this class had better diction than kids in other classes with the same background?

Yes. And I began to ask Carrie Secret, “What are you doing differently?” She told me about the Standard English Proficiency Program. So when a kid did not make the -ing sound, or left off a consonant, or made a word singular when it should be plural, or plural when it should be singular, Carrie would repeat back to the young people until they began to hear the correct word.

How did she do it?

The child says, “I’m going wit my mother.” Or, “I’m goin home.” She says, “Where?” And the child says, “I’m going to go home.”

When you heard children speaking Standard English, you were thrilled. You’re sounding like the critics of your own Ebonics resolution.

Standard English is (necessary) to go to a four-year college, to being accepted in an apprenticeship program, to understanding the world of technology, to communicating. We owe it to our kids to give them the best that we’ve got.

There’s great disagreement over Black English as a language, a language “pattern,” or just street slang. What is Black English?

All I know is that it’s not slang. The linguists call that “lazy English.” But our children come to school with this language pattern. Go back to what they call the Negro spiritual: “I’m going to lay my ‘ligion down.” That was the code song that got you your ticket on the Underground Railroad. It’s the way the words were used. So they might have thought we were old dumb slaves, but it served a purpose. It was communication.

Do some parents and children resist speaking Standard English because they really see it as white English?

I don’t think they consciously resist. My youngest daughter has had that criticism: “You talk like a white girl.” It’s another way of saying, “How come you don’t sound like us?” It hurts to be accused of that. When I was a girl, it was a goal to speak Standard English, not a ridicule. I have no idea how that changed.

Why don’t children automatically know Standard English, since they hear it all the time on television and at school?

Two things. African Americans whose economic status and exposure is closer to that of Huxtables have the exposure to work with the youngsters and teach them about the “two-ness” of the world they’re involved in. But some schools are located in very depressed areas, have a primary population of African Americans on a fixed income. They see very little, the young people are exposed to very little, and there isn’t a whole lot of reason in the home — this is just my guess — to adopt the behavior of duality.

Do you believe that the language pattern of Black English is genetic?

It’s ancestral. “Genetic” doesn’t say “in your blood, in your biology.” It says, “in the beginning!”

Following that logic, why don’t other ethnic groups use the grammar of their immigrant ancestors?

No other group in America, outside the Native Americans, ever had to grope (as we did) with the new language. If you didn’t get off the Good Ship Lollypop speaking English, learning it was exacerbated by the fact that you had to sneak to teach yourself. Then if you stay together in an isolated, segregated environment, the language pattern persists over time.

And yet there are millions of African Americans who speak with no trace of Ebonics.

And there are an awful lot of second-and third-generation Chinese who speak perfect English, but when they go home to grandmother, they make the switch.

And many African Americans don’t. Is this an issue of class?

In some instances, it is class. You know, having come from a family of educators, it was a symbol of your ability to speak the King’s English. I remember my mother telling me the tragedy is that as those kids became comfortable with the tools of the middle class, one of which was language, they began to turn their backs on their parents. They were embarrassed about their language style.

This is the traditional immigrant experience. What’s unusual is for children to cling to the language patterns of their elders.

Here is where it’s confusing to some, but to others, I think they have ulterior motives.

What’s the ulterior motive?

The English Only campaign. We talked informally among the school board members. Be careful, don’t get caught up in the English Only campaign.

And the ulterior motive is the anti-affirmative action movement?

The funding is from the same platform, Right-wing America. It used to be that we’d just simply say it was racism. But now they are so sophisticated that it’s about being anti-Black, anti-Jewish, anti-

immigrant, anti anything that’s not Christian. Anti-urban, anti-female, I mean they just kind of took everybody and threw us all over there together. We have no allies over there. None whatsoever.

If nothing else, you’ve gotten them to add anti-Ebonics to the list. But you’ve also gotten many people on your side, haven’t you?

I’d love to be able to tell you how we plotted and planned to become the topic of everybody’s conversation in the world. That’s dishonest. It took me by surprise.

You had been very opposed to changing any of the controversial wording in your resolution — that Ebonics is “genetically based,” for instance and that students will be taught “in Ebonics.” Yet you changed your mind. What happened?

Sometimes you have to look: Are you winning the battle but losing the war? The African-American Task Force met (for about 10 hours) last week and got no closure on the word “genetics.” Oscar Wright, the old man of the group, said, “If removal of this word will heal the pain of the African-American community, then remove the word.” When that old man gave the word, we moved on. I felt fine about that. I would have stayed on course, but the village said to do things differently.

Did you grow up speaking Ebonics?

No, but I heard it. You’ve got to think about coming up in a segregated time. In 1954, when the school desegregation decision came, I was 10. But the more I think about it, the more I think about how blessed I’ve been. Both of my parents had graduate degrees. My dad was a dentist. My mom was a linguist with the National Security Agency. We were never quite sure what she really did. We know she spoke perfect Russian. We used to say Mom was a spy for the FBI. And we always thought that Mommy was the smartest thing we ever saw.

So language and politics were always entwined in your family?

Everyone in my family, whether it was Mom or Dad, they were always crusaders. You never earned the right to snub your nose at anybody based on speech patterns. I remember a time when we went down the street, and a drunk said something to my sister Twink, and she laughed. Mom gave her a backhand, and said, “That man meant nothing but to be kind. Go back and say: “How do you do, sir?” She was serious. My mother was 4-foot-9, and 89 pounds, boy. And she spoke perfect English.