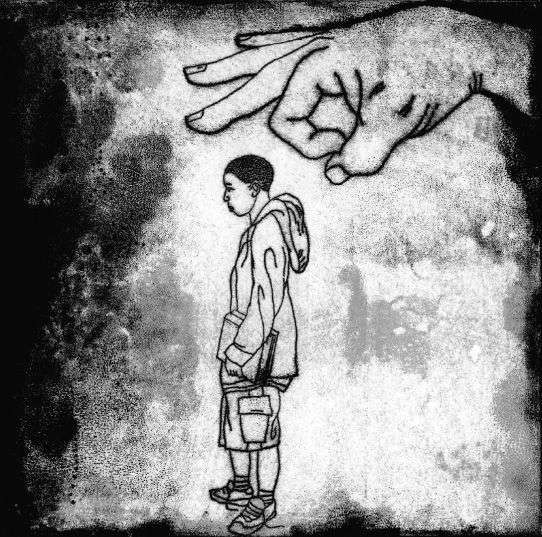

More Than a Statistic

Reflections on the black side of school discipline

Illustrator: Richard Downs

“In your silence, you have become an accessory to murder!”

In his role as Dr. Vernon Johns, a Civil Rights leader, actor James Earl Jones vehemently indicts a complacent congregation that is too busy assimilating in white society to protest police brutality in the Southern 1950s. In my silence, I, too, have become an accessory — not to murder, though the long-term effects can be just as devastating to a community.

Xavier (a pseudonym) is not the first black boy whom I silently watched being treated unjustly while trying to survive in school under the weight of being black and poor and improperly raised within a dysfunctional family. A 23-year veteran educator of the public school system, I have observed innumerable incidents with countless Xaviers that contribute to the disproportionate rate at which black children are suspended.

These black children are more real to me than the alarming statistics that declare African American children are two times more likely to be expelled than white children. Xavier is the face behind these statistics. One unseasonably warm October morning, instead of lining up with his class to prepare for entry into the school building, Xavier lingers in the wrong line while chatting and laughing with friends. When approached by an administrator, Xavier responds, “My mistake,” and begins to walk to his appropriate line. The administrator directs Xavier (along with two other boys) to go to the main office where he must sign a statement that he intentionally — not mistakenly — stood in the wrong line.

For reasons that may only be clear to other black boys, Xavier refuses to write a confession while the other two boys (who are not African American) comply immediately. Xavier’s obstinacy results in him spending almost a day and a half out of the classroom and in the office. Here’s a kid who, against insurmountable odds, has made dramatic improvements. Unlike the disheveled, disorganized, disinterested boy I met in 4th grade, 6th-grade Xavier comes to school regularly; he is relatively clean; and he is usually prepared to work and learn. He is rewarded for that effort, for that remarkable transformation, with an in-school suspension for what is not aberrant behavior for children — talking to friends for a few seconds longer than they should when it is time to line up. In fact, on this particular day, most of the 6th-grade population is out of compliance.

Let’s imagine the same scenario with a blond, blue-eyed white girl. The child is caught talking in the wrong line and mutters, “My mistake,” before dashing off to catch up with her class. More than statistics can ever reveal, my personal and professional experiences tell me she would have been allowed to join her class with or without a quick admonishment to not let it happen again. A few seconds later — case closed — education is not disrupted. When a black boy is involved, however, it frequently turns into an event. Unfortunately for Xavier and thousands like him, his events are often limited to the emotional posturing and battle of wills that take place in public schools all over this country until he graduates (if statistics bear out) to his big event, admission to the penal system.

Months earlier, I am silent when I witness a black boy being singled out unfairly. It is at the tip of spring. The warm air is slowly casting off the harshness of winter. It is also a Friday with a number of substitute teachers in the building, so the children are more spirited than usual. Bursting out the door during a fire drill, one upper-grade ethnically diverse class, with Latino, Indian, Pakistani, Caucasian, and African American students, teeters on the verge of being out of control. There is loud talking, infectious laughter, and friendly taps as they explode past me in a blur of youthful exuberance with their teacher seemingly oblivious to it all.

Abruptly, this joyous — albeit inappropriate — mayhem is interrupted when a quiet black boy makes the fatal error of pulling his hood onto his head. A teacher begins yelling at that child as if he is the one who is playing during a fire drill. I cannot make out the teacher’s words, but the venom that drips from every syllable is perceptible even at a distance. I catch up with the group in time to hear the teenager spew, “I’m sick of your ass! It doesn’t matter what everybody else is doing because all you see is me!”

Even knowing that this child has just given voice to the private thoughts that ricochet through my mind, I say nothing as his teacher herds him to the office amidst a torrent of shared animosity. I utter no protestations as another black boy racks up more suspension days. To be sure, the child is wrong for using profanity, and he has a history of losing control. I am not asking for a free pass every time a black student disrespects an authority figure, but how much self-control would you possess if every move you made were scrutinized contemptuously?

As a 45-year-old black woman whose mere presence on the street still compels white and Hispanic women to clutch their purses tightly to their breasts, I understand the frustration and anxiety that tied that adolescent in knots, rendering him incapable of socially correct discourse. It is difficult to be constantly regarded with suspicion and disapproval and bear the burden of knowing that the people in power are just waiting for you to screw up. Under such scrutiny, it is impossible for that boy and many like him to knit together the appropriately respectful words needed to defend their missteps.

That event is preceded by one with a black girl, the only dark complexioned female in the room. She is kicked out of class for talking. This child’s event escalates to such heights that by day’s end she is the recipient of a three-day suspension. Like Xavier, she has put forth considerable effort to turn her life around and become a productive member of the school community after two years of troublesome behavior. Never quite recovering from her event, she remains somewhat disconnected and disenchanted for the rest of her 8th-grade year. Since his event, Xavier, too, has lost his footing and has experienced a notable increase in the number of infractions he amasses before his mother eventually transfers him to another school.

Situations like these abound because honest and productive conversations with teachers and administrators who are not black are rare due to an unspoken perception that we (African Americans) are labeling them racists. Yet what permeates the American psyche runs much deeper than that. Police brutality, for example, can be dispensed just as easily and just as viciously with black hands. In fact, a black administrator assigns the three-day suspension to the black girl who at first only wants to know, “Why am I being kicked out and nothing is happening to Mary (the white girl with whom she was conversing)?”

In response to the alarming suspension rates, I have heard many educators opine that more black children are suspended because they misbehave more frequently than white children. In my mind, such simplistic analysis ignores the many variables that contribute to both the real and imagined offenses perpetrated by black children.

The problem is that some of our black children are not allowed to just stop — to err and move on. We adults (of all races) have developed a habit of escalating the conflict when the child is black — especially if he is a boy. Black boys tend not to get warnings and quiet admonishments. They are simply removed — out of line, out of class, and eventually out of school. It is no wonder the dropout rate is soaring in the black community.

Shortly before 11:00 a.m. on the second day of his punishment, Xavier signs the confession after his mother informs him via the telephone that she is not returning to the school. I do not know what important life lesson he is supposed to have learned during his exile from class, but I suspect Xavier is learning what it means to be a black man in America. And I am learning that I can no longer be an accessory.