‘Let Your Motto Be Resistance’

The Real Lesson of Amistad

“What has happened in history is not what necessarily gets recorded as history.” This is the first line of a book I am completing on what I call the slave(ry) trade, cotton, and the industrial revolution in textiles in Great Britain and New England. In an era when the media is almost all-powerful in shaping public opinion, we also face a decline in historical literacy. We are thus a nation at risk of having its understanding of history shaped more by Hollywood than by historians and history teachers. This is a particular challenge to educators.

The contradiction between Hollywood’s version of history and history as it happened is about to be revealed again with the forthcoming movie Amistad by producer Steven Spielberg. This contradiction is receiving more-than-usual attention because Spielberg is being sued by an African-American woman, Barbara Chase-Riboud. She claims “his” script stole “her” story which she told in her 1985 book, Echo ofLions.

In a story in its Nov. 24 issue, Time magazine suggests that the controversy may fan the embers of a continuing Black-Jewish confrontation about media control and the larger debate about who “owns” history. In the meantime, the facts and, more important, the real meanings and lessons of the Amistad rebellion will perhaps be lost to another generation. Two of the most important lessons are that oppressed people will seek to liberate themselves “by any means necessary,” to quote Malcolm X, and that friends among the oppressor group sometimes may be moved to strike blows for the freedom of the oppressed.

Though the story of the Amistad rarely has been mentioned in history books, it has resonated in African and Afro-American history for almost a century and a half. What worries me most about Spielburg’s Amistad is what worried me about Mississippi Burning, The Ghosts of Mississippi, and several other Black history-related movies. In the drive to make a commercial movie, the movie and the movie-makers — and their version of the story — become the main issues, instead of the “history” the movie claims it wants to tell.

THE AMISTAD STORY

In 1839, a group of 53 Africans from the Mende nation were illegally captured near what is now Sierra Leone and brought by Spanish merchants to Cuba. After being imprisoned in a jail-like barracoon, they were sold as slaves and were being transported on the ship Amistad — ironically, the Spanish word for friendship — from Havana to a slave plantation in another part of the island. Bad weather hampered the short journey. When the Africans were told by an African cook working for the slavers that they would be killed and eaten, the Africans revolted.

Led by a young man named Cinque, the Africans rose in revolt, killed the captain, and seized the ship. For almost two months, the Africans attempted to sail back to Africa, only to be tricked by crew members they did not kill. Instead they were captured off the coast of Long Island and imprisoned in Connecticut. The Amistad incident became a rallying point and key battle for the movement to abolish slavery. A group comprised mainly of white abolitionists organized as The Amistad Committee orchestrated the legal defense of the Africans. Black aboltionists also were involved.

The U.S. Congress, despite a gag rule passed by the House which sought to prohibit anti-slavery petitions, also took up the controversy. President Martin Van Buren sided with the Spanish slavers, and some scholars claim this cost him votes in the North and led to his defeat in 1848. Representatives of Britain, Spain, and Cuba also became involved, indicating the international significance of the slave trade and slavery.

The Amistad case was eventually heard before the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled that the Africans had been captured illegally and that they should be allowed to return to Africa. John Quincy Adams, the former U.S. President, argued on the Africans’ behalf before the Supreme Court. But no “great man theory of history” perspective should be invoked to hide the more important fact that many others worked not only on the Amistad case but also in the broader movement to abolish slavery.

The Amistad Committee finally raised the funds to transport the 35 Africans back to their homeland. On Nov. 27, 1841, a group of missionaries which included two Black people, sailed on the Gentleman and reached Sierra Leone seven weeks later.

SEPARATING MYTH FROM TRUTH

So much of the current discussion of the movie Amistad misses key points. For example, promotional material for the movie and comments by lawyers jockeying for legal advantage distort history. Some promotional material, for example, claims that the Amistad incident was the first successful slave revolt, whatever that means. Yet the celebrated slave revolts of Gabriel Prosser, Denmark Vesey, and Nat Turner took place in between 1800 and 1822, and there were hundreds of others. Further, such a claim ignores that any and all slave revolts were successful! They signaled to the ruling master-class that Africans would not submit to enslavement and “go quietly into the night.” The Amistad rebellion was a bold statement which trumpeted the same sentiments later echoed by Boston Black abolitionist Henry Highland Garnet: “Let Your Motto Be Resistance.” Along with other revolts, they undoubtedly hampered the expansion of slavery and the slave trade.

In the movie Amistad, Morgan Freeman plays a Black abolitionist. Chase-Riboud’s lawyer, in their attempt to prove that Spielberg lifted from her script, claims that this character could not be based on a real figure because there were no such Black people at the time. Nothing could be further from the truth, and it distorts Black history to suggest otherwise. Boston Black freedom fighter David Walker, for example, published his militant anti-slavery Appeal in 1829. Rev. J.W.C. Pennington of Hartford, a well-trained and fiery Black minister and abolitionist who wrote one of the first Black history textbooks in 1841, Textbook of the Origin and History of the Colored People, is another example. In fact, the Black church and Black ministers were prime examples of the important support that free Black men and women gave to the struggle to abolish slavery, a tradition which was nobly continued with the efforts of the Massachusetts 54th Regiment and others during the Civil War.

The Amistad has surged through Black history for over 150 years and it is unfortunate that so few people know the full story. In 1846, The Amistad Committee joined others in becoming the American Missionary Association (AMA). After the Civil War, the AMA helped found Dillard, Tougaloo, Talladega, Fist, and several other Black colleges and universities. Margru, one of the three young girls among the Amistad captives, returned to Africa and then came back to the U.S. to study at Oberlin. She later returned to Africa to teach at the AMA Mende Mission. One of the first students educated at the mission also came to the United States to study at Oberlin and was a founder of what became Florida A. and M. University, an historically Black university in Tallahassee.

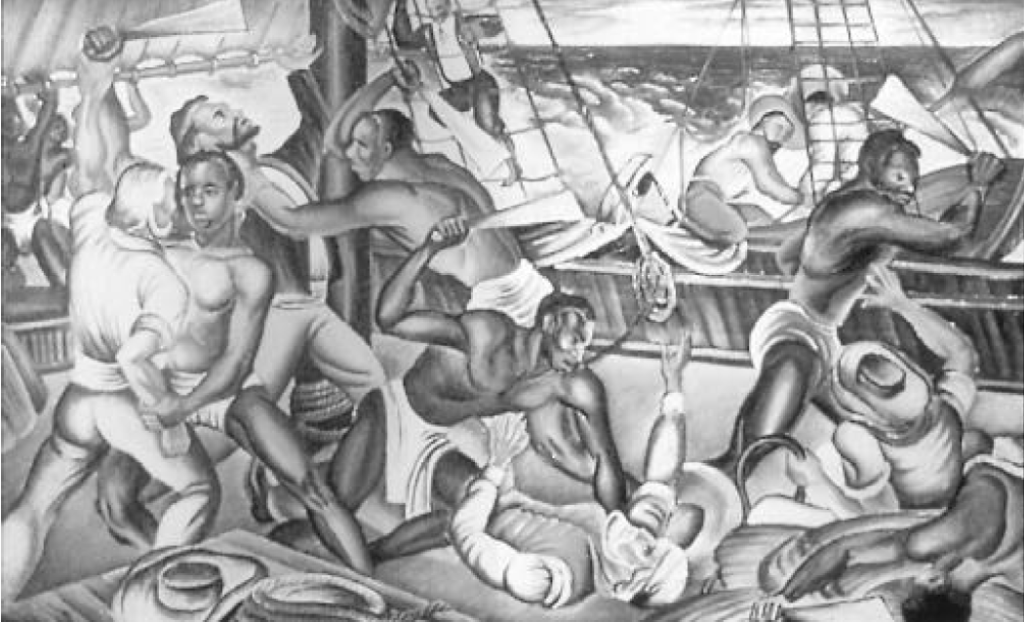

Black people have long recognized and celebrated the Amistad’s significance. At Talladega, a Black college in Alabama, the artist Hale Woodruff was commissioned to complete large murals on the Amistad in the 1930s and his work still graces its library. Margaret Walker, the noted African-American novelist (Jubilee) and poet (“For My People”) wrote these lines: “… Cinque, O man magnificent … Bequeath to us your handsome dignity and lordly noble trust.” In 1970, the novelist John A. Williams (The Man Who Cried I Am) and publisher Charles Harris launched a journal call Amistad, a project which evolved into a publishing house and now a series edited by Henry Louis Gates of Harvard University.

Recognition of the Amistad’s powerful model for resistance was not all academic and cultural. In 1974, a group calling itself The Symbionese Liberation Army kidnapped newspaper heiress Patty Hearst. The leader of the group called himself “Cinque,” honoring the young, spirited leader of the Amistad revolt.

LESSONS FOR THE NEW MILLENNIUM

In this period when race relations are at such a low point, it is imperative that we raise up lessons of history that clarify our current situation. We also need historical models that point the way forward to improved relations. Like the story of John Brown who organized white and Black abolitionists in attacking the slave system, so, too, does the Amistad incident represent Black and white unity against the most prevalent form of oppression in that time.

The Amistad incident was intimately connected to other key events in what was one of the most formative periods of U.S. and world history: the transformation of the old world into the new, the rise of modernity — which slavery and the slave(ry) trade helped bring about. If we are ever to solve the contemporary problems of race and class relations, we must understand the contributions of African peoples and their descendants in the Americas to capitalism and the modern world.

To cite one important example: most of the world’s sugar, which fueled world commerce in the 1700s, and more than 90% of the world’s cotton, which fed the textile trade and the industrial revolution in the 1800s, was produced by “slaves” — people of African descent — in the U.S. and the Caribbean. This is why I have called my book Those Valuable People, the Africans.

Slavery and slave produced goods were central to both the growing problems between Great Britain and her American colonies, and to financing U.S. economic independence after the American Revolution. In short, without American slavery, there could have been no American freedom. “We, the people” are all products of this history. Our understanding of issues of race, class, gender, nationality — and who we are as a people, facing the new millennium — must begin at this beginning.

The Amistad story is truly the people’s story, and no amount of commercial posturing by any party should be allowed to distort this. It belongs not to Steven Spielberg nor to Barbara Chase-Riboud but to all of us.

There are many stories that Hollywood should be telling. We cannot and should not have to wait until the stories arrive in the heads of producers or others who don’t know the stories but seem to know when a profit can be made from some version of them.