‘I Just Want to Read Frog and Toad’

Another child's love of reading runs smack into No Child Left Behind

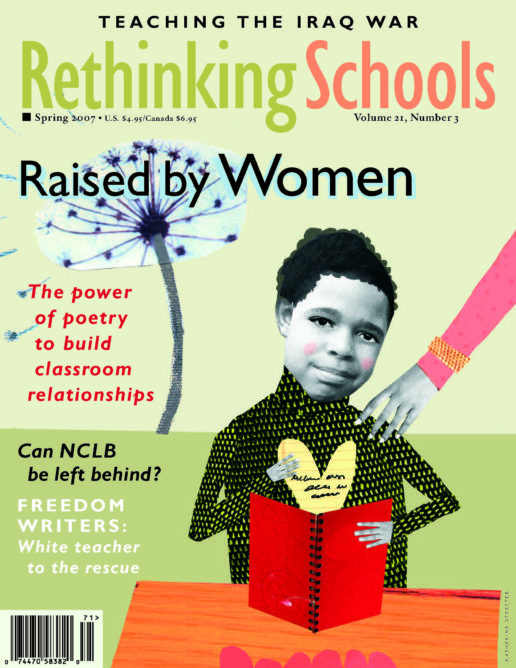

Illustrator: Stephen Kroninger

One mid-September night, when I was tucking my 5-year-old son Eamonn in bed, the standardization madness came home to roost. With quivering lip and tear-filled eyes, Eamonn told me he hated school. He said he had to read baby books that didn’t make sense and that he was in the “dummy group.”

Then he looked up at me and said, “I just want to read Frog and Toad.”

I am an experienced elementary teacher and college professor, with a long-standing disdain for “ability” grouping, dummied-down curriculum, and stupid, phonics-driven stories that make no sense. And yet here I was, seemingly unable to prevent my own child from being crushed by a scripted reading program of the type so beloved by No Child Left Behind (NCLB).

What’s So Bad?

Eamonn had left kindergarten happy and confident, even requesting his own library card that summer. His older brother and sister were wonderful role models who had enjoyed sitting at the kitchen table on dreary Northwest days writing and illustrating their own books and, when they were older, reading chapter books in bed before they fell asleep.

But then the desire to quickly “fix” struggling readers and standardize curriculum descended on the primary grades at his school.

When my son had been in kindergarten, the 1st and 2nd-grade classroom teachers, with the principal’s strong urging, had looked at two scripted programs: SRA/McGraw-Hill’s “Open Court Reading” and “Houghton Mifflin Reading.” When I heard about this, I spoke to the Site Council, principal, and teachers in an effort to persuade them to instead focus on improved teaching using authentic literature. The principal assured me that a decision to buy either program was on hold.

That fall, however, I opened the Welcome Back to School Newsletter and read that the Houghton Mifflin program would be used for the 1st and 2nd grades. Mixed in with feelings of dismay and anger, I felt guilty that I had not fought harder to ensure that the scripted curriculum was not adopted.

After Eamonn’s lament about Frog and Toad, I decided to do further investigation. I grabbed Eamonn’s backpack and found a wad of photocopied “books” and a 20-page chunk of stapled-together workbook pages.

Limiting Vocabulary

One of the photocopied “books” was The Big Pig’s Bib. I’d give a synopsis of the tale, but it makes no sense and is little more than a collection of unrelated words. The story begins by introducing the human characters and saying, “It is Tim and it is Mim.” In standard English, the word this would be used to introduce Tim and Mim — i.e., “This is Tim and this is Mim.” Unfortunately, the program has not yet presented the word this, so instead it introduces the characters using clumsy, non-standard English: “It is Tim and it is Mim.”

At one point, the story says the pig is not big but then at the end, Tim and Mim fit it with a “big pig’s bib” — even though there are no events or clues as to how the pig, who was not big, can now wear a “big pig’s bib.”

Then there’s the story of Can Pat Nap? The simplistic line drawings show a child sitting down under a tree. In the tree is a bird that one assumes is a woodpecker. The text reads, “Pat can nap. Tap, tap, tap. Pat can not nap. Tap, Tap, Tap. Sap on the cap. Can Pat nap? Not here, Pat!”

I am confused. Can Pat nap or can’t he? Better still, who cares?

A Waste of Resources

The workbook pages, meanwhile, are supposed to coincide with the books but are little more than simplified skills. One asks the student to circle short “I” sounds; another asks the children to draw a diagonal line from one part of a compound word to another. All of the writing and thinking is done by the publisher, and the children merely fill in disjointed blanks. Once they identify the pattern, there is no need to even read the surrounding text.

There are a few pages that ask for some sort of thought process, for example to write an alternate ending for a story. Unfortunately, those exercises have been crossed out. Apparently, having children actually think and write takes up too much time.

After a few days, I cooled down enough to approach the principal, classroom teacher, and reading teacher. I asked that Eamonn be allowed to read real books and during workbook time, to write his own stories in a journal. I was assured accommodations would be made. (It turns out, however, that they weren’t.)

Life continued at its hectic pace. Eamonn stopped crying about reading, and he seemed relatively happy with school. Weeks, then months, passed.

Capitalizing on Students’ Interests — or Not

The following spring, as we sat on the couch one afternoon, Eamonn offered that reading was beginning to be fun. I asked why. “Well, since it is at the end of the year, we are getting to read words like ‘about’ and our reading workbook and worksheet packets ask us to fill in the blanks with bigger words,” he explained. “All year until now the blanks have been for little words like, ‘I,’ ‘I,’ ‘I.'”

Eamonn hopped up excitedly and ran to his backpack to show me a book he had just gotten. He pulled out a photocopied book, Number 71, entitled White Knight. On the cover was a whimsical knight dressed in armor with a large “W” on his shirt and a banner with WK on it. Then Eamonn said, “See, it is a knight!”

Eamonn explained that the students were also excited because the teacher had handed out the book to the class a while earlier, but then taken it back. “She goofed up,” he said. “See she had all these books copied and ready and she passed out the wrong number. We had other ones we had to read first before we could get to this number. We had not read numbers 69 and 70 yet.”

While the Houghton Mifflin program boasts of quality stories from well-known children’s authors, those apparently are sparingly dispersed in the classroom. The photocopied books sent home for children to read and add to their “library” are boring both textually and visually, filled with black-lined drawings of androgynous human characters.

And then there is the case of the “White Knight” with the large W on his chest, perpetuating stereotypes of the damsel in distress being rescued by the white knight who “always does what is right.”

Eamonn opened up the four-page book and read:

(Page 1) White Knight said,

“I am brave. I fight for what is right!”(Page 2) Miss Moll was up high. She called, “White Knight! White Knight!”

(Page 3) White Knight climbed high to get Miss Moll, but he did not hang on tight. He fell on his thigh.

(Page 4) Miss Moll came down to White Knight. She said, “You might like some pie.” White Knight sighed.

At the end of the reading, Eamonn’s head dropped and he looked up with disappointment. “Well, that wasn’t very good,” he admitted.

But then he proceeded to tell his own story: “It could have been that the White Knight is going by a dragon and he pulls out his sword — this might be bad but there could be blood — and he kills the dragon and then he goes to the castle and battles the guards. Then he runs up a bunch of stairs, and he rescues Miss Moll. When they are running down the stairs, there are new guards and he battles them. Then they get on horses and ride past the dead dragon, ride off down the road and get to their castle and live happily every after.”

“That could be a good story,” he says proudly.

What could I say? I affirmed what he already knew: that stories need to be complete, not exercises in the “long i spelled igh.” And Eamonn’s story actually had a plot. It had a beginning, middle and end, a problem and a solution, a protagonist and an antagonist. Unfortunately, the main lesson he took from White Knight was the reinforcement of the damsel in distress stereotype.

I am angry that Eamonn did not get to write his own knight story, and that he and his classmates were denied the opportunity to critically think about the stereotype being perpetuated in White Knight. Instead he had his time wasted by filling in “about” on a workbook page while the teacher tried to distribute the next book in chronological order.

This fall, Eamonn started 2nd grade and his teacher granted my request that he be allowed to read actual books during reading time, not photocopied nonsense. He has become an avid reader and falls asleep every night with a book in his hand. He prefers reading real books with real stories — the kind you find in public libraries and bookstores but, increasingly, not in our nation’s elementary classrooms.