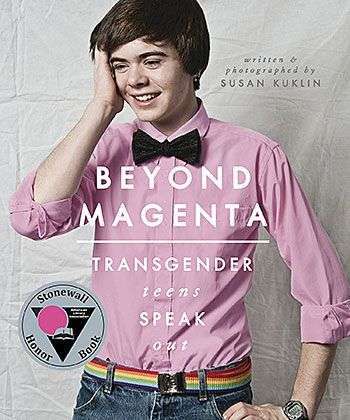

Beyond Magenta

Words and photographs by Susan Kuklin

(Candlewick Press, 2014)

“You have got to come out here and see this!” That’s how a transgender student was introduced to her homeroom teacher at a high school in my district. When I heard the story from a friend, it brought me almost to tears. How could one human being refer to another with such disrespect? Unfortunately, this is the awful reality for far too many trans youth in our schools.

Susan Kuklin first caught my attention a few years ago when I was browsing at the public library. Her book Families includes oral interviews and photographs of biracial families, families with divorced parents, gay and lesbian families with children. (See “Disarming the Nuclear Family,” by Willow McCormick, summer 2014.) Although Families does not include all the kinds of families in my large urban district (e.g., blended families, extended families, or children living with other guardians), we have had great conversations about the book in my early elementary classrooms. A year later, when I was leading professional development workshops on gender and sexuality, a colleague pointed me to Beyond Magenta: Transgender Teens Speak Out.

The award-winning Beyond Magenta is for youth, parents, and educators. It illuminates the lives of transgender and questioning teens and their parents through photos and interviews. First we meet Jesse, who shares photos of himself as a child named Jessica, as a high school student, and then through his transition. Jesse’s story is positive: His family has accepted him and he is in a happy relationship.

Christina describes her more difficult transition from male to female. Christina’s mother, who is also interviewed, warns readers: “Don’t say horrible things to your child. That will haunt me till the day I die.”

Mariah was moved between foster homes, treatment centers, hospitals, and a psychiatric center. Nat is an intersex youth whose struggle with identity led to serious depression.

Then there is Cameron, who explains: “Gender is one variable in a person’s identity, and sexual orientation is another variable. The two are not connected. Being trans is not the next step to being gay. They are similar in that they are both breaking gender rules. I like to think that’s obvious, but I guess it’s not.” Cameron, who uses the pronoun they, describes themself as pansexual — “I like people regardless of gender” — and their style as “gender fuck” — “blending stuff, having something girl and something boy and something neither.”

The individuality of the youth voices in Beyond Magenta makes it clear that we cannot assume that all transgender teens share the same experience. Each person’s story is unique.

Beyond Magenta includes a glossary and resources. In the question and answer section, Manel Silva, former clinical director of Health Outreach to Teens at the Callen-Lorde Community Health Center in New York City, addresses questions about the transition process.

Kuklin has written a book that is easily accessible to teens and adults. Although it will serve as a comfort for trans and questioning youth, Kuklin asks us to think about what the information means to the rest of us: “Once we get to know individuals who may be different from ourselves, it is less likely we will be wary of them. And maybe, just maybe, we will learn a little bit about ourselves.”