Preview of Article:

Embracing a Vision of Social Justice in Early Childhood Education

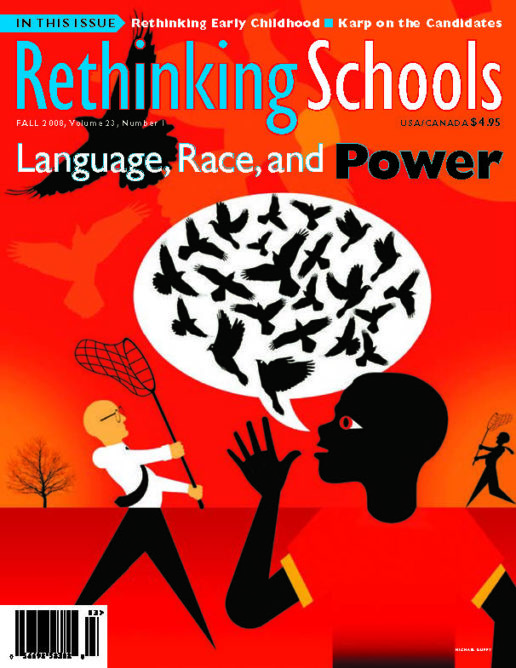

Illustrator: David McLimans

This essay is the introduction to Rethinking Early Childhood Education, edited by Ann Pelo, and published this month by Rethinking Schools.

— editors

There’s a small town in Italy with an international reputation for its early childhood programs. The teaching and learning that happens in their schools is certainly compelling — but more compelling is the story of how the community came together to create an early childhood education system. The town of Reggio Emilia, like much of Italy, was devastated by World War II; as the war ended, the townspeople were fiercely determined to create a new culture, a culture in which the fascism that had taken hold of Italy in the decades leading up to the war would find no foothold. The citizens of Reggio Emilia were clear about how to begin this work of culture-building: they would create schools for young children.