Disarming the Nuclear Family

Creating a classroom book that reflects the class

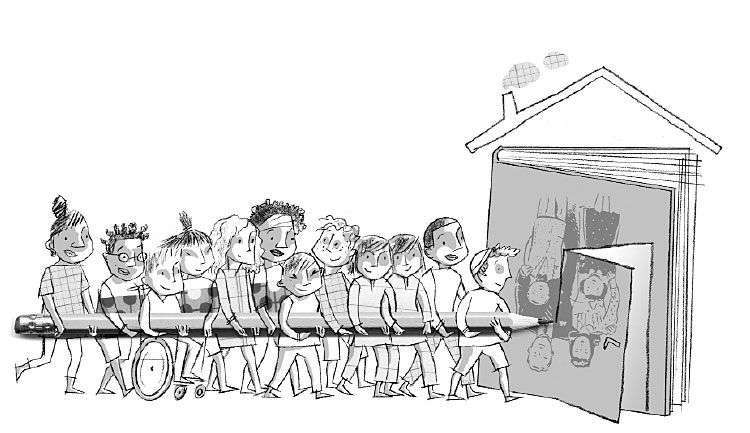

Illustrator: Christiane Grauert

I have more than 1,000 books in my classroom library, cobbled together from garage sales, used bookstores, and the collections of former students who have outgrown their picture books. As a social justice educator, I try to fill my primary classroom library with books that feature characters from a variety of cultures, traditions, classes, and backgrounds. And yet, despite my efforts, I’m dismayed by how many of the thoughtful, well-written books in my collection feature the nuclear family unit, be it human or animal. Even my favorite authors default to the nuke.

Kevin Henkes is a perennial favorite in primary classrooms across the country. The mice that populate his books cope with universal struggles of young children—separation anxiety, teasing, loneliness, empathy. Unfortunately, Henkes’ books present something else as universal as well: a doting mother and father plus a sibling or two waiting at home to soothe and support the struggler.

Trudy Ludwig has written an excellent collection of books, including Trouble Talk and Sorry!, that dig into the power dynamics among children and offer strategies on how a child can transition from being a target to a self-advocate—with a little help from Mom, Dad, and brother in a tidy, suburban home. The message of empowerment is a noble and essential one, which is why I read these books to my class every year. But another message is being conveyed as well when these books are read back to back: two-parent heterosexual families are the norm.

When a book does acknowledge the existence of other family structures, the difference is often the focus of the story—how Addison has two fancy houses instead of one in Tamara Schmitz’s Standing on My Own Two Feet: A Child’s Affirmation of Love in the Midst of Divorce. If you want to read a story featuring children in foster care, you’ll have to look long and hard for anything other than guides for making the transition in or out of care. It takes a lot of work to find books that include same-gender parents, step-parents, foster or adoptive children, or other nontraditional families as background in an adventure tale, a friendship parable, or a holiday romp; nontraditional families are either the topic of the story or, more likely, not included at all.

When two-parent, heterosexual families are presented as the norm in story after story, year in and year out, an insidious message is conveyed: Families that don’t conform to this structure are not normal. And, of course, the message is reinforced in the majority of movies and television shows geared toward children. Shame, secrecy, and evasion can result from this incessant messaging.

I see it play out in my classroom. Two years ago, I had a student with divorced lesbian moms, step-siblings, half-siblings, and a close-knit extended family. I doubt any children’s book out there includes a family like hers. They were a loud and loving family, and Marie was a loud and loving girl. Yet she rarely divulged that she had two moms and, in fact, fabricated an absentee dad at one point early in the year. Another boy, Andrew, didn’t want anyone to know he was adopted, afraid they would think he was “weird.” He said it was hard enough having brown skin when his parents and most of his classmates were white; he didn’t want kids to think of him as different in another way, too. I pride myself on having an accepting and appreciative classroom community, but the undermining effect of the dominant family system in children’s books and media slips into our snug community like toxic smoke.

What is a 2nd-grade teacher to do? Dispose of all Kevin Henkes books, and deprive 7-year-olds of the pleasure of repeating “Chrysanthemum, Chrysanthemum, Chrysanthemum” as they root for the main character to embrace her unusual name and accept herself? Give periodic rambling qualifiers before read-alouds, trying to explain the heteronormative paradigm in kid-friendly language? Build a library where every family structure is represented equally, thus ensuring a library of 100 books or fewer? I’ve considered all of these scenarios in moments of exasperation, but nothing seems realistic.

Susan Kuklin’s Families

Luckily there are resources out there that shine a light on a path forward. A few years ago I discovered a beautiful book by Susan Kuklin simply titled Families. Kuklin puts family structure in a larger context of diversity of all types. To create the book, she interviewed children aged 4 to 14 from a variety of family structures, mainly in New York City, but also in rural communities. She then worked with the children to select a page’s worth of text describing their family members, religious traditions, household, hobbies, and studies. A family portrait accompanies each page; the children themselves chose the location, clothing worn by all family members, pets, and props. The net effect is a refreshingly matter-of-fact look at 16 very different families. Ella is a summer camp aficionado who was adopted by her two fathers as a baby. There’s also Kira and Matias, biracial children who live beside a creek and love catching fish for dinner. Yaakov, Leah, Miriam, and Asher are Orthodox Jews who make themselves laugh with goofy invented languages. Chris, Louie, and Adam are close-knit brothers whose parents come from Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic; they discuss food and language, only mentioning in passing that Louie has Down syndrome.

We Make Our Own Book

This book has all sorts of potential for classroom use. I use it as a mentor text for writing our own class book of families. Each day I read aloud one family story to the class. The straightforward tone of the book leads easily to a straightforward discussion afterward. I ask the kids to make connections between the family we just met in the book and their own families, or the families of their friends or neighbors. What do they have in common? What are some differences? The class often starts with the goofy languages—they make up silly words, too!—or the hobbies or study habits they share with the children in the book. But it’s not long before the conversation gets more personal. Finn mentions his gay aunts, two children of divorced families compare how they split up—or don’t—their time between households, devout Christian Isaiah notices that he and a Muslim boy in the book both consider themselves servants of God.

Over time, we begin to craft our own narratives. First we brainstorm themes that came up again and again in the book—food, religion, traditions, sports and hobbies, descriptions of family members—and the kids start to make lists from their own lives that fit into these categories. Then they write, each in their own style. Ramona tells how her cousins came to live with her family as foster children. “My mom wanted to know how long they would be staying, but now we’re all glad they came.” Isaiah tells us that religion is the biggest part of his family’s life. Marie writes about her two moms, and Rory explains that he doesn’t have a dad or siblings, but his uncles and pets fill in, and he and his mom have an extra special relationship because it’s just the two of them. Andrew, after a few fretful conferences with a couple of trusted peers and me, decides to include his adoption in his narrative:

Hi, I am Andrew. I am 8 years old. I have one sister and no brothers. I live in Oregon. I was adopted because my birth mom could not take care of me. My dad was at work then the phone rang. Somebody said into the phone, “Jon, do you want to be a dad?” “Yes!” After one day my mom and my dad came to the place where I was. My new mom and dad took me home.

Once the narratives are crafted, the kids bring in photos to use as illustrations, or direct me to photograph them doing things they love at school. They paste their narratives and photos to oversized construction paper to create their own page in our classroom edition of Families.

To draw the project to a close, I host a writing celebration in the classroom. The children lay their pages out carefully on the tables and we spend the hour rotating from desk to desk, reading stories and leaving notes of praise and connection. “My family goes hiking on Easter, too!” “You have two moms?! You are sooo lucky!”

At the end of the day, I collect all pages and bind them together. Now there’s at least one book in our classroom library where all of my students can find themselves. When I think about how intently the majority of my students read and respond to the writing of their peers, I realize that, even if my classroom were fully stocked with high-quality literature featuring a complete spectrum of family structures, I’d still want this book, our book, at the center of my library. It is satisfying for the students to see themselves reflected in the books and other media that surround them. But it is also powerful—and comforting—for children to see and be seen by their own peers. Ultimately I want both for my students: a world in which they feel they belong, and a classroom community in which they feel known.