“Did Any of You Just Search for ‘Physicist’?”

Exploring Racism and Privilege in Physics Class

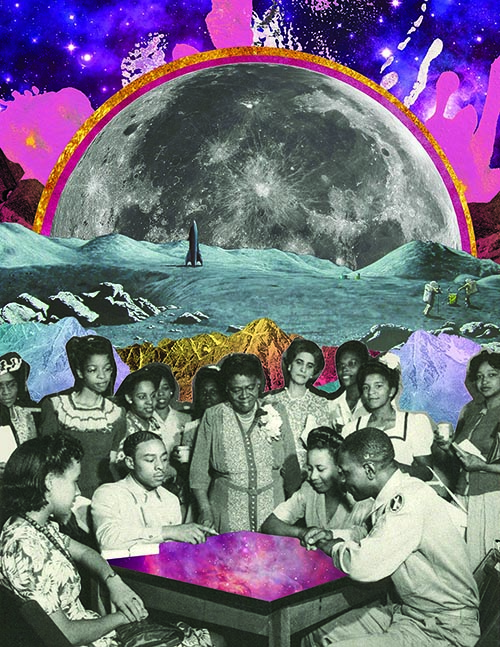

Illustrator: Kendrick Daye

Staring at the Google Images search results for “physicist” projected in front of the class, Luke remarked, “When I look at famous physicists I see people who look like me.”

“When I look, I don’t,” responded Chris.

Luke, like 80 percent of the students in my 12th-grade physics elective, is white, and Chris is Black, and is one of the few students of color in my class. And they were both right: The images predominantly showed white, male faces.

We were halfway through a unit exploring racial privilege and how it impacts the field of physics and my students’ lives. To start class that day, I’d asked them to consider if their racial identities influenced their experiences as a science student.

Most students initially said no, and so this moment marked the first connection they made between their racial identity and the different ways that the culture of physics welcomes or excludes them. It would be the first of many revealing moments to come as part of our larger curriculum connecting physics and demographics to systemic racism and privilege.

This connection hasn’t always come easily to me as a teacher. Physics is a discipline generally more focused on ramps and falling objects than identity and society.

I teach in a majority-white private school in majority-white North Seattle. Most of our students come from the north part of town, and my classes tend to reflect the demographics of our school as a whole.

All my students, regardless of their racial identity, experience the privilege of attending an elite private school: Every one of them will go on to attend a four-year college, and the language of power and entitlement that they learn in school, as well as their connection with the alumni network, puts them on a fast track to future positions of wealth and power.

That’s why it’s so critical that we develop spaces in our school curriculum for our students to talk about this privilege, about what it means, and how it impacts them and others. My white students are largely unaware, just as I was at their age, of the ways that their race has shaped how they are treated. At the same time, several of my students of color have made it clear how much of themselves they feel they must leave outside our building.

A central theme of physics is the use of data to answer questions, and it occurred to me that my students could learn about systemic racism by examining the field of physics itself. Census data give a snapshot of the racial makeup of the United States, and the National Science Foundation’s “Women, Minorities and Persons with Disabilities in Science and Engineering” offers a similar look into the population of U.S. scientists, engineers, and mathematicians.

We compare the two data sets as a class, numerically and graphically, and discuss how to quantitatively assess whether the number of Black and white physicists are balanced appropriately, since the populations are different sizes. This exercise in proportional reasoning leads to a stark reality: A white American is three times more likely to become a physicist than a Black American.

My students spend the year using collected data to explore the driving forces behind observed phenomena. And so in this unit, we simply continue: Having identified the racial disparity in the physics profession through our data analysis, we proceed to study the underlying societal forces it reveals.

Although the ensuing exploration of systemic racism may not be what the creators of the Next Generation Science Standards had in mind with their cross-cutting scientific concept of “investigating and explaining causal relationships and the mechanisms by which they are mediated,” this is nonetheless exactly what my students are doing. We use the tools and practices of science to learn about society and social justice.

On the first night of the unit, I ask my students to learn about one Black physicist who did their work before 1950 as well as one working today, and come to class ready to share what they’ve discovered. Part of my motivation is to expand the range of physicists that my students learn about; it’s not a hard assignment, and that’s partially the point. The physicists my students have learned about throughout their lives have been overwhelmingly white and male — Newton, Galileo, Tesla, Hawking, Einstein — and many studies have shown that this filtered selection of scientists influences how all students perceive science and their place in it.

By asking my students to actively seek out Black physicists, I am also expanding their conception of who can do science. The morning after this homework I asked, “Who did you find?”

They excitedly shared with one another about Warren Henry, George Carruthers, Shirley Ann Jackson, Chanda Prescod-Weinstein, and many more.

I follow with the question, “How did you find them?”

“I Googled ‘African American physicist'” replied Stephanie, as several heads nodded in agreement.Ê

“I sort of did the same thing,” said Monai, “but I used ‘Black physicist.'”

“Me, too,” said Esther.

“Did any of you just search for ‘physicist’?” I asked. They didn’t, they say, because they know (without having thought about it) that doing so only brings up white faces. “What search terms would you have used if I’d asked you to find a white physicist?” I asked. They recognized that they would have been able to search simply for “physicist,” and, to deepen the connection, this is when I projected the Google Images search results for “physicist” on the board.

“It’s like how Serena Williams is called the best female athlete, but Marshawn Lynch is never referred to as a male athlete, it’s just assumed,” noted Tina.

“Great connection, Tina!” I exclaimed. “What do you think are the effects of framing them that way?”

“It makes Serena seem like she’s being measured by a different standard,” Tina said. “And it’s implied that that standard is a lower one, instead of her just being considered the best overall.”

Gender and racial discrimination are not the same, of course, but my white students’ awareness of the former often provides them a way in to thinking systemically about race. One student later wrote in the journal in which I ask them to reflect each day:

When you’re part of the majority you’re looked at as just an individual, but when you’re part of a minority, people see what you do as representative of your group. For Black physicists, they could have the added pressure that anything they do could be taken to say something about all Black people.

I wanted this conversation, and the unit as a whole, to shift both how my students think of physics and how they think of their own experiences. We had shifted gently into a conversation about who is included, and who is excluded, from the picture of physics that we — individually and societally — hold in our heads.

This leads us back to the central question of the unit: Why are there so few Black physicists?

On the unit’s second day, I have the class begin by thinking about their own lives. “You’re going to write for a bit about how you’ve developed the interests you have,” I told them. “Think of something that you like: How did you come to like it? It might feel inevitable, but try to remember the encouragement and obstacles you experienced along the way. I’m going to ask you to discuss with a partner afterward, but you won’t have to share what you write if you don’t want. Be honest as you write.”

Leah noted that having a female cello teacher meant she always had a musical role model to look to; Allen shared a memory of how his teachers seemed to praise his mathematical talents more than his equally capable female peers. In our discussion, the students seemed aware that their development was not inevitable, but had been shaped by many factors outside of themselves.

“Knowing What You Know, What Can You Do?”

When I first taught this unit, the project ended after several more days spent exploring racial privilege and implicit bias, with students able to describe systemic racial oppression in the United States and how it might contribute to the lack of Black physicists. But when I asked my students for feedback on the lesson they made it clear that I couldn’t leave them having explored only the problems. “This feels awful,” said Jason, and the nodding of his classmates meant, to me, that we’d be spending more time with this.

“OK,” I said, “knowing what you know, what can you do?” This is a hard question, of course, for anyone to consider, and as the room went silent I thought about ways to give my students more of a foothold. “Think back to what you’ve learned about your own experiences and how they have been shaped by your race. Think about the different ways that racism operates,” I said.

Once they had time to reflect and write, I asked them to write their thoughts — and then responses to the thoughts of others — on large Post-its around the room.

Their specific actionable suggestions focused on the importance of representation and role models, on changing the face of science as it’s taught in schools and through pop culture. Brian suggested that I could start the year by printing and posting a picture of every scientist mentioned in class, slowly painting a picture of under-representation without needing to say a word.

Rebecca was so inspired by what she’d learned that she organized a group of her peers to go into the 6th-grade science classroom that’s part of our school to share the stories of a diverse group of scientists. The 6th-grade teacher and students were delighted, and my students felt like they were making a small but tangible difference. Other students have written letters to our administration advocating for more faculty of color and done an audit of our physical campus through the lens of disability access and justice.

One student had the idea to create posters publicizing the Black physicists they researched on the first day of class and to put them up around school, and it was a student’s idea to cover those posters with a cover sheet asking the viewer to “Picture a Physicist” so that the rest of the school could come face-to-face with the same cognitive dissonance they encountered in their research and reflection. I’ve since adopted this as a required part of the curriculum.

The physics that high school students learn is often far removed from what actual physicists do, and these posters (and my insistence that students summarize their subject’s work and research anything they don’t understand) are set up to try to narrow this gap. As a science teacher, I want my students to learn about the work that physicists do in the real world. As an activist, I also want them to engage in the important work of broadening our school and our society’s definitions of who physicists are and what they look like.

Of course, I still see ways in which this unit falls short. I am happy to open my white students’ eyes to the challenges faced by Black physicists and Black scientists trying to enter the field, but know that I also need to help my white students recognize the costs that systemic racism enacts on their own humanity. I continue to struggle with how to offer a unit that helps my mostly white students learn about racism without ignoring and marginalizing my students of color; over time, my planning has increasingly centered their experience. And though I want to keep diving deeply into race, I know I want to keep bringing in other identities and oppressions into my students’ learning.

Happily, I see growth in my students’ reflections and the class environment as a whole. Monica, a Latinx student, wrote that our discussions provided her an opportunity to share the ways that her experience at school was so different from her white peers, and for those peers to better understand why. In anonymous surveys before the unit, 73 percent of my students of color reported that they felt they could be themselves in this class; just two weeks later, following the unit, all 100 percent agreed. Alissa, a white student interested in studying marine biology in college, wrote in her reflection:

I’ve learned a lot during this project. I’ve learned how to have a brave conversation, how to better navigate these difficult topics, how being white affects me in many different ways, how the lack of Black physicists is looked at and what can be done to change it. . . . As the project progressed, I found myself . . . being more willing and able to view being white as yes, something that gives me an inherent privilege but also being able to recognize that and start thinking about how I can use that and how I can change the world around me to be more level and equal for everyone.

I developed this unit by considering the social justice needs of my student population, and by asking myself how I could address them in the context of my scientific discipline. Through data analysis, through hypothesis formation and validation, through exploring the culture of physics and the experience of individual scientists, I believe this unit improved my students’ skills both as scientists and as activists.

By bringing social justice into science class, students can see, as one student recognized in their post-unit reflection, that “social justice applies to everyone, everywhere, at any time.”

Resources

National Science Foundation, National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics. 2017. Women, Minorities, and Persons with Disabilities in Science and Engineering: 2017. Special Report NSF 17-310. Arlington, VA. Available at www.nsf.gov/statistics/wmpd/.

The Under-Representation Curriculum resources are available at underrep.com