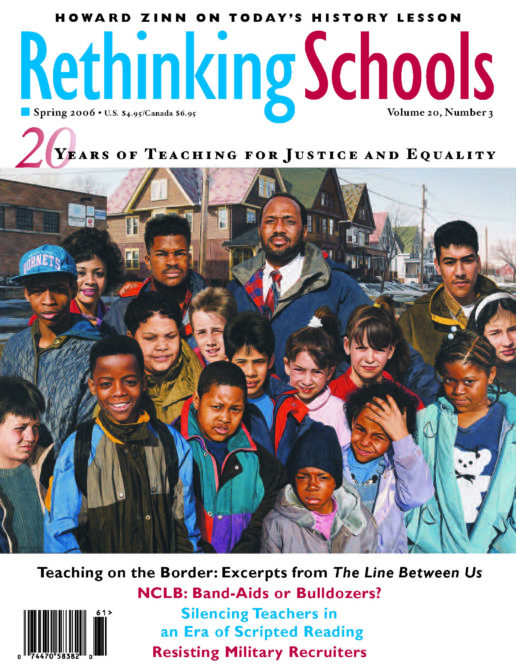

Defending Bilingual Education

English language learners come to school with a built-in opportunity to become bilingual. Schools should help them seize this opportunity.

Illustrator: Alain Pilon

After six days straight of standardized testing in English, her second language, Ana lost it. She laughed out loud and the rest of us laughed with her. As her 4th-grade teacher I was expected to keep order and continue administering the test (which I did), but I could see where she was coming from. Perhaps it was the rigorous schedule: seven days of testing for three hours each morning. Perhaps it was the tedious format: listen as each test item is read aloud twice in English and twice in Spanish, then wait for all students to mark an answer, then move on to the next test item. Perhaps it was the random nature of some of the questions.

Whatever it was, Ana knew it didn’t make sense. That moment has become a metaphor to me. There are more English language learners than ever in U.S. schools, and yet the policies that affect their schooling make less and less sense.

About 10 percent of all U.S. students — more than five million children — are English language learners. This represents a tremendous resource and opportunity. If schools serve English language learners well, at least 10 percent of U.S. students can have highly valued skills: fluency in more than one language and an ability to work with diverse groups of people. If communities give English-speaking students the opportunity to learn side by side with students who speak other languages, an even greater number of students can learn these skills.

But there are obstacles. Although research shows that bilingual education works, top-down policies increasingly push English-only education. To make matters worse, schools serving immigrants are some of the most segregated, understaffed, under-resourced schools in the country.

In our Winter 2002/03 editorial, Rethinking Schools wrote that “bilingual education is a human and civil right.” I think all teachers should defend this right and demand equal educational opportunities for English language learners. It’s not just about immigrant students: U.S. society as a whole will benefit greatly when all students have access to bilingual education, and when schools serve English language learners well.

Bilingual Education Works

Research shows that bilingual education is effective with English learners, both in helping them learn English and in supporting academic achievement in the content areas.

A synthesis of research recently published by Cambridge University Press showed that English learners do better in school when they participate in programs that are designed to help them learn English. The review also found that “almost all evaluations of K-12 students show that students who have been educated in bilingual classrooms, particularly in long-term programs that aim for a high level of bilingualism, do as well as or better on standardized tests than students in comparison groups of English-learners in English-only programs.”

A synthesis of studies on language-minority students’ academic achievement published in 1992 by Virginia Collier found that students do better academically in their second language when they have more instruction in their primary language, combined with balanced support in the second language.

I have seen this in action at the two-way immersion school where I teach 4th grade. Spanish-dominant students who develop good literacy skills in Spanish have a far easier time in 3rd and 4th grade when they begin to read, write, and do academic work in English. Likewise, students who struggle to read and write in Spanish do not transition easily to English reading, and they tend to lag behind in English content-area instruction. High-quality Spanish language instruction starting in kindergarten is essential. Without it, Spanish-dominant students do not get a fair chance to develop good literacy and academic skills in their first or second language.

More Need, Less Bilingual Instruction

Despite the evidence that properly implemented bilingual education works for English language learners, English learners are being pushed into English-only programs or getting less instruction in their primary languages.

Voters in three states (California, 1998; Arizona, 2000; Massachusetts, 2002) have passed referenda mandating “English-only” education and outlawing bilingual instruction. (Colorado defeated a similar referendum in 2002.) Although many parents in these states hoped to get waivers so their children could continue bilingual education, they had more luck in some places than others.

In Arizona, one-third of English language learners were enrolled in bilingual education before voters passed Proposition 203 in 2000. Although Proposition 203 allowed waivers, the state’s Superintendent of Public Instruction insisted on a strict interpretation of the law that denied waivers to most parents. Eventually almost all of Arizona’s bilingual programs were discontinued; the National Association for Bilingual Education noted in October of 2005 that “bilingual education is simply no longer available” to English language learners in Arizona.

Prior to the passage of Question 2 in Massachusetts in 2002, 23 percent of that state’s roughly 50,000 English learners were enrolled in bilingual education. By 2005, only about 5 percent were in bilingual programs. Under the new law it is easier for children older than 10 to get waivers, so middle and high school students are more likely to participate in bilingual education than elementary students. Students do not need a waiver to participate in two-way bilingual programs; in 2005 there were 822 students enrolled in two-way bilingual programs.

Resistance Saves Some Programs

In California, the first state to pass an English-only referendum in 1998, some schools were able to continue offering bilingual education. The law required all districts to inform parents of their option to continue in bilingual education by signing a waiver; some schools and districts succeeded in getting a very high percentage of waivers and continuing their programs. But by 1999, researchers at the University of California Linguistic Minority Research Institute found that only 12 percent of English learners were in bilingual programs, compared to 29 percent before the law changed.

Researchers also found that districts that had a strong commitment to primary language programs were able to hold on to those programs after Proposition 227 passed, while districts that were “not especially supportive of primary language programs prior to 1998” were more likely to do away with primary language instruction altogether.

The “English-HURRY!” Approach

Even in places where bilingual education is still permitted (by law or by waiver), top-down pressures threaten to weaken it. Since the passage of NCLB, standardized testing in English has put pressure on schools to teach English earlier and to do it faster.

Bilingual education is still legal in Wisconsin, where I teach. Milwaukee has a districtwide developmental bilingual (also called “late-exit”) program. This means that children learn to read and write first in their primary language (in our case, Spanish), and in the early grades they are taught all subjects in Spanish. Once they have gained a strong footing in Spanish, they transition to English and start to receive a larger percentage of literacy and content area instruction in English. Even after making the transition to English, students can continue to get a significant portion of their literacy and content area instruction in Spanish for as many years as they choose to stay in the bilingual program.

But since the passage of NCLB, our district’s developmental bilingual program has not fared as well as one might hope. In 2002, Wisconsin did away with all of its Spanish-language standardized tests and began requiring almost all English language learners to take standardized tests in English starting in 3rd grade. (Wisconsin could have purchased and administered tests in Spanish, but chose not to do so because of the cost.)

The English tests have changed classroom instruction for bilingual students in our district. District administrators, many principals, and lots of teachers have bought into the idea that kids must learn English sooner because they must score well on English language tests. “Hurry up and teach kids to read in English! They’ve got to be ready to take the 3rd-grade reading test in English! They’ve got to be ready to take the 4th-grade WKCE in English!” Suddenly a lot of what we know about second-language acquisition has fallen by the wayside in the scramble to get kids to do well on tests so we can keep schools off the list.

At my school, the year after the law changed, I was part of a team of teachers and administrators that met for months to decide how to respond to the reality that our Spanish-dominant students would be tested in English starting in 3rd grade. We ultimately decided to transition children to English reading in the 2nd and 3rd grades. (We had previously transitioned students to reading in their second language at the end of 3rd grade and beginning of 4th grade.) Other schools in my district have also pushed the transition to English to earlier grades. Still others have reduced primary language instruction in the early grades to make room for direct instruction in English reading (for Spanish-speaking students) as early as 1st grade.

There has been little public discussion about these changes, which contradict the research because they decrease the amount of primary-language instruction and allow less time for students to establish solid literacy skills in their primary language before beginning the transition to second-language literacy. Instead of engaging in discussion about these changes, many administrators and some teachers dismiss concerns with a common refrain: “This is what we have to do to get them ready for the tests.”

In a report called “The Initial Impact of Proposition 227 on the Instruction of English Learners,” researchers in California described how bilingual instruction changed when English-only testing began:

English-only testing was observed to have an extraordinary effect on English learner instruction, causing teachers to leapfrog much of the normal literacy instruction and go directly to English word recognition or phonics, bereft of meaning or context. Teachers also worried greatly that if they spent time orienting the children to broader literacy activities like storytelling, story sequencing activities, reading for meaning, or writing and vocabulary development in the primary language, that their students would not be gaining the skills that would be tested on the standardized test in English. They feared that this could result in the school and the students suffering sanctions imposed by the law.

Thus, even in the classrooms that had been designated as bilingual, and where principals often contended that little had changed, teachers revealed that their teaching practices had indeed changed substantially and that their students were receiving much less literacy instruction in their primary language.

Ironically, the NCLB does not specify what language students should be taught in, nor does it even require that students be tested in English. It specifies that students must be tested “in a valid and reliable manner,” and that they should be given “reasonable accommodations,” including “to the extent practicable, assessments in the language and form most likely to yield accurate data on what such students know and can do.”

But states have chosen to implement the law in a variety of ways. Most states test students exclusively in English. Some states give English learners extra time to take the test. Another common accommodation is to translate or simplify the English on portions of the test. The state of California allows no accommodations for students who have been in the California schools for one year. Ten California districts have filed suit claiming this violates the NCLB’s provision that students be tested in a valid and reliable manner with reasonable accommodations.

Segregation and Unequal Resources

These recent changes in language and testing policies are making a bad situation worse for English language learners, many of whom were already experiencing some of the worst educational conditions in the country.

A study published by the Urban Institute in September 2005 noted that the majority of English language learners are “segregated in schools serving primarily ELL and immigrant children.” The study found that these “high-LEP” schools (defined as schools where Limited English Proficient students comprise 23.5 percent or more of the student body) tend to be large and urban, with a student body that is largely minority (77 percent) and largely poor (72 percent). In addition, “high-LEP schools face more difficulties filling teaching vacancies and are more likely to rely on unqualified and substitute teachers,” and teachers are “more likely to have provisional, emergency, or temporary certification than are those in other schools.”

Researchers at the University of California, Davis, in 2003 found similar disadvantages for the schooling of English language learners, saying they faced “intense segregation into schools and classrooms that place [English learners] at particularly high risk for educational failure.”

Advocacy for Immigrants

As conditions and policies worsen for English learners, there is an urgent need for teachers, families, and language-minority communities to speak up in favor of immigrant students and bilingual education.

It is important for English learners to succeed academically and to become bilingual, especially now. Many U.S. cities have majority-minority populations, and more and more people in the United States speak languages other than English. To be able to successfully live in and lead this diverse society, people need to learn how to value and accept others. All children need to learn how to communicate with people whose language and culture are different from their own.

These abilities are highly valued, and many teenagers and adults spend years trying to develop them. Children who are raised from birth speaking a language other than English have a unique opportunity to cultivate these abilities from a young age. Our schools must help them seize that opportunity.