Creative Conflict

Collaborative playwriting

Illustrator: Colin Matthes

The conflict in my classroom was explosive: defiant teenagers, raging parents, broken promises, betrayal among friends. Students were on their feet, shoving furniture, glaring menacingly, raising their voices. As I surveyed the room, part of me was very pleased.

In some ways, the project this class had undertaken—creating collaborative plays about issues important in students’ lives—was going very well. The students, 20 high school seniors, seemed engaged and invested in the work, from brainstorming and improvising to writing and revising. The class had read and watched a variety of dramatic pieces, and students had already written and performed some excellent monologues and short scenes. For this unit, we had started by generating an exhaustive list of themes and issues that interested students in the class. In the end, the students narrowed the list down to three topics—peer pressure, sexuality, and domestic abuse—and formed collaborative playwriting groups to explore each issue and create original plays.

The students were also proving that they had a clear understanding of one of the foundational concepts in playwriting—conflict. For the purposes of playwriting in our class, I had defined conflict in this way:

Conflict = want + obstacle

In order for an interesting conflict to develop, a character must have a want or need (for example, a young woman wants to play basketball), and there must also be something or someone standing in the way (for example, her grandma forbids her to leave the house). Students agreed that conflict is what makes drama interesting, and they quickly learned to incorporate it into the scenes they wrote in class.

The Conflict

In the midst of this creative process, however, I was troubled. Many of the scenes being enacted in the room were scenes of violence, and it was hard for me to watch my students play this out. Some of the violence I saw in students’ work was physical violence taking place between characters. In one scene, two young women attacked each other in a dispute over a young man; in another, a mother beat her teenage daughter. I also noticed some vicious verbal abuse among characters who were spouses, siblings, and classmates. Given the topics students had chosen to explore, including peer pressure and domestic abuse, the violence was not surprising. I was committed to giving students authorial and creative control, but I still worried about the impact of these representations of violence, both on my student playwrights and on a potential audience of community members. What would it say about my students if they wrote and performed plays full of verbal and physical violence? Wouldn’t it reinforce some of the most pernicious stereotypes about urban youth?

The first and simplest answer that occurred to me was to censor their work. I knew that if I tried this, they would lose some of their passion for playwriting, and we would all lose some of the integrity of the creative process.

As a teacher, I was facing an important conflict. My “want” was for my students to experience the power of creative, collaborative work. I hoped that writing plays would give them an opportunity to develop their voices and explore complex issues with one another. I imagined plays that could provide a more nuanced, authentic view of my students’ lives than a media that often portrays urban youth as reckless and destructive. The “obstacle” in my way was that their work, in fact, resembled many of the TV shows and movies that I hated for their flat, negative portrayals of young people. How could I push their thinking beyond the stereotypes they saw in the media? How could I bring this conflict in my teaching to a productive resolution?

The Want

In playwriting, the most powerful wants are those with high stakes. High stakes means there is a lot to gain and also a lot to lose. This is how I felt about my “want” for the playwriting class. It was my third year teaching this class, an elective that I designed in collaboration with Philadelphia Young Playwrights, a local arts education organization. My prior experience had taught me that playwriting could evoke powerful responses from my students. In creating characters and settings, students shared their perceptions of the world—what they found admirable, despicable, exciting, ideal. In crafting dialogue, they found a safe haven for the rhythms and vocabulary that best portrayed their realities; because plays often employ dialect, I was able to take a break from policing their writing and embrace the rich nuances of non-standard English. And finally, in performing each other’s work, students built community and confidence as artists.

Standing before a group of 20 restless seniors, I wanted all of this and more. I also wanted to give my seniors a space to address some of the issues that were on their minds as they contemplated the end of high school. Just as playwriting can create a safe space for students to express themselves in non-standard English, it can also create a space to explore the issues that are rarely discussed in school. In class, we looked at examples of plays that take on complex topics like race, sexuality, violence, and identity. We studied Fences, The Laramie Project, and the work of Anna Deveare Smith. We looked at ways playwrights draw on multiple sources (history, memory, interviews, music, news) to create a meaningful whole with a powerful message. I wanted my students to be able to harness this same creative power in their work.

The Obstacle

In playwriting, the obstacle is what gets in the way of the want. It’s the forbidding parent, the envious sibling, the mountain that must be climbed. For me, it was the violence being acted out all over my classroom. Students were enacting not only physical and emotional violence, but also a kind of violence of representation. The caricatures they put on stage—from the obnoxious, aggressive mother to the single-mindedly promiscuous young woman—stood in the way of my vision of a more authentic, nuanced portrayal. And instead of provoking thought, these caricatures elicited guffaws and groans from our class audience. My students and I had seen these characters before: on TV or in movies. Re-enacted in our room, the stereotypes seemed familiar and amusing to some, predictable and boring to others.

I was confronting what Marsha Pincus refers to as “a moment of dissonance.” My desire to promote real artistic control and a real creative process had led to stereotypes that made me cringe. How could I redirect my students toward creating more nuanced characters? How could I support them in teasing out more authentic portrayals?

Luckily, thanks to a partnership with Philadelphia Young Playwrights, I shared this class with a brilliant teaching artist, John Jarboe. John and I talked together about our concerns and tried to address them with the class. We led a discussion about stereotypes and brainstormed a list of stereotypical characters from TV and film. Then, we challenged our students to go beyond the stereotypes, to dig deeper for more complex, realistic characters.

Our students were attached to the characters they had created. Exaggerated stereotypes are funny, they contended. And in some ways, they were right. In the case of a play about sexuality, seeing the “whore,” the “player,” and the “virgin” parade across the stage did elicit laughter from the class in rehearsals.

Another group argued that they had already defied a stereotype in their play on domestic violence. They had cast the abuser, a role typically filled by a man, as a woman, an aggressive mother who incessantly insulted her husband and daughter. Although I applauded them for exploring a new angle and their classmates rewarded them with hearty laughter during rehearsals, I still felt that their portrayal was more of a caricature than an authentic imagining of a real problem.

I realized that my challenge now was to prove to my students that there could be a more gratifying response to drama than just laughter. I believed that if they were willing to leave the relative safety of stereotypes, they could move audiences with their work. I just wasn’t sure how to get them to believe.

Resolution and Final Product

Every great conflict in a play must end in a satisfying resolution. The question must be answered, the tension dissolved. The resolution of the conflict in my practice was not neat or easy, but it was deeply satisfying—certainly for me, and I hope for my students as well.

It began when I found a way to invite my students to bring their own experiences into their work. Initially, this proved difficult. Students had intentionally chosen controversial topics because they wanted to use their plays to raise questions about “things that don’t get talked about.” Many students had selected issues that were important to them for personal reasons, but very few were willing to share their personal experiences with sexuality, domestic abuse, and peer pressure. Without their authentic experiences informing the plays, however, we were left with empty caricatures and recycled stereotypes.

I talked with the students about the importance of taking risks in their work, and we agreed that the best way to make the plays more powerful and authentic was to incorporate real, lived experiences. For each play topic, I developed a set of writing prompts that I hoped would elicit a broad range of reflections and experiences. I realized that there were some assumptions in the class about whose voices mattered. For example, only those who had had sex could really speak meaningfully about sexuality; only those who had been abused could really speak meaningfully about domestic abuse. To counter these perceptions, I was careful to frame questions that everyone could answer. Writing prompts on the topic of sexuality, for example, included: How did you learn about sexuality? When? Where? Write about a time that you learned about sexuality in school. Write about someone you know who has been given a label (for example, player, whore, fag) that has to do with their sexuality. Why do you think this person was labeled? How do you think he or she feels?

I posted the sexuality questions at the front of the room and gave students time to write. I asked that they write anonymously so we might be able to use the writing to develop and revise our plays. Then I collected all the student writing into a packet. I told the class that I planned to give the packet of writing to the collaborative playwriting group that was working on the play about sexuality and that I hoped that the writing might help them weave more authentic experiences into the fabric of their play. I made a point of including my own writing in the packet, and I asked if anyone wanted their writing removed from the packet. Surprisingly, no one did.

We went through the same process for both domestic abuse and peer pressure. By the end of class, we had three packets of writing, each filled with student reflections on the play topics. The next day, students gathered into their collaborative playwriting groups, and I distributed each packet to the corresponding group. I passed out highlighters and asked the groups to pass each piece of writing around their table, reading silently and highlighting words or phrases that stood out to them. Inevitably, there was some speculation about the authors of different pieces of writing, but for the most part, students were engrossed in reading and respectful of their classmates’ honesty and willingness to take a risk for the sake of improving the plays.

Once everyone had finished reading and highlighting, I asked the class to create “mash-up” poems made up of the highlighted words and phrases. Each group worked collaboratively to piece together their classmates’ words into rhythmic chains of impressions and reflections. The next day, members from each group performed the poems for the rest of the class.

The performances were powerful, in part because many of us heard our own words echoed back to us as poetry. There was also a shared sense of working together to paint an authentic picture around these important issues. The poems were not cohesive or neat, but they were drawn from real voices—our voices.

After the poetry performances, the playwriting groups revised their plays. One group used their mash-up poem as the final scene in their play. Another used vignettes from the writing activity as transitions between the scenes in their play. All of the plays became richer and more nuanced.

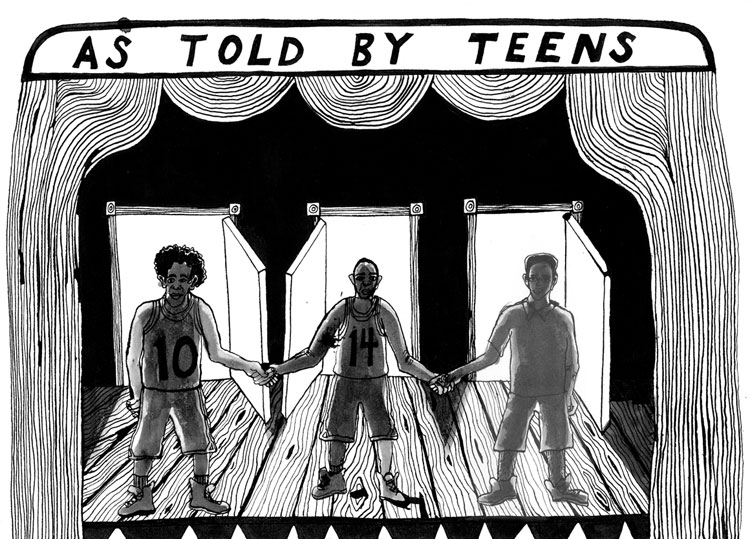

The group that had chosen sexuality as their topic decided to name their play As Told by Teens. It includes one scene that I find particularly moving and that I feel represents the resolution that my students and I were seeking:

(Jerry, Sean, and Jahlil are walking into the locker room; all guys begin to get changed.)

Jerry: Yo, fellas, I gotta tell y’all something important and it has to stay between the three of us OK.

(They all stop. Sean and Jahlil turn around and give Jerry a concerned look.)

Jahlil: Uhh, OK, what’s up?

Jerry: So it’s like this, y’all remember that time we was out and I was talking to the dude who I said owed me money?

Sean: Yeah, what about him?

Jerry: Well, the thing is that he didn’t really owe me money . . . I was kind of . . . sort of . . . getting his number.

(There is a pause as all three boys look at each other.)

Jahlil: So you’re telling us . . .

Sean: That you . . .

Jerry: Yeah . . .

Sean: How long have you known?

Jerry: For about a couple years.

Jahlil: (Harshly) So all these years we’ve been together, chilling and shit, you suddenly have these thoughts that damn, I think I wanna be gay from now on!?

Sean: Yo, dude, chill.

Jerry: It’s not even like that. It’s nothing that you can just decide like, oh, I feel like wearing sneaks today or flip-flops tomorrow. I didn’t know. I wasn’t sure.

Jahlil: Naw, you know I don’t play that gay stuff!

Sean: Yo, Jahlil, you way outta pocket right now, like what is your problem? That’s our friend right there.

Jahlil: My problem is that this is someone we be hanging around.

(Turns his attention to Jerry)

And if you think to even try to come at me with that gay stuff, then best believe that it will be a problem. Without second-guessing, I will knock you out.

Jerry: Really, though!? I told y’all this in 100 percent confidence because I thought that both of y’all was my friend. And then you snap on me like this. Some real friends y’all are.

Sean: (Getting between both of them)

Will both of you shut the hell up for a minute!

(The room gets silent for a moment then Sean continues to speak.)

Now listen, Jerry’s gay . . . who the hell cares? He’s been our friend since we was in grade school, he’s had our back throughout the most difficult days that we had.

Jerry: So why the hell—

Sean: Shut up.

(Jerry gets quiet again.)

Nothing about him changed . . . other than his sexual interest.

Jahlil: Sean, you know I don’t associate myself with those kind of people.

Jerry: (Hitting his boiling point) Those people?

(Trying to get past Sean but is stopped.)

You know what, fine, I got you. Oh, I got you.

(Picks up his stuff and walks out.)

Sean: Dude, what the hell is wrong with you?

Jahlil: Nothing is wrong with me. I’m not going to sit around and wait for Jerry to try and pull some gay stuff on me. You know what, forget this. I’m leaving.

(Picks up his stuff and begins to walk out)

Sean: Where are you going? We have to get changed for practice.

Jahlil: I’m going home. I ain’t gonna be around that gay stuff. Peace.

(Jahlil exits. Sean picks up his things and leaves, shaking his head as he exits.)

Reaction and Reflection

This scene, and many of the other scenes in the plays, show my students as they really are: passionate, thoughtful, complex, working hard to navigate the changing terrain of their relationships and their world. Jerry and Sean defy the stereotype of the homophobic black male, and by the end of the play, so does Jahlil; his loyalty to his friend Jerry triumphs over his initial discomfort.

Still, I worried about how the play would be received. We had planned to perform it for an audience of family, friends, students, and teachers. I worried that parents and teachers might think these topics had no place in school. I worried that students in the audience might laugh or call out during some of the tenser scenes. I was worried that my student-performers might be disappointed if they didn’t garner the applause and plaudits I thought they deserved.

I stood nervously in the back of the auditorium as As Told by Teens unfolded. As the students performed what we called “the coming out scene,” I held my breath, anticipating some kind of explosion from the audience. There were gasps and a few giggles, but nothing extreme. Mostly, the audience seemed enthralled by the conflict on stage. In the scene directly following this one, Jerry delivers a monologue in which he claims his right to be open and feel comfortable about his sexuality. After his final words, the audience exploded into applause.

The success of the plays is a testament to the brave creativity of the playwright-performers and to the warm acceptance of our school community. I thought about the students in the audience who were gay, lesbian, or bisexual. How did it feel for them to hear that applause? To know that not just a few of their teachers, but a whole audience of peers and community members applauded the decision to come out? This message of acceptance was a unique and powerful result of the students’ work. It was not something that a teacher or a guest speaker or a school policy—no matter how great—could deliver. It was made possible only through the original work of students, writing and performing for and with their own community.

In the end, both the plays and the conflict in my practice came to satisfying resolutions. But neither one ever felt like a foregone conclusion. Most days during the semester I felt overwhelmed by how many things could go wrong. I often felt like I was in over my head or that I had opened a Pandora’s box that I couldn’t shut. But I’m glad I stuck with it, and I hope to do this type of work with students again in the future. I know that there will be new conflicts—in the playwriting and in my practice—but I have a lot more faith in the process of working through them with my students. Freeing students to pursue the creative process and address controversial issues felt scary and even dangerous. Acknowledging and embracing the conflict in my practice felt risky and destabilizing at times. But the conflict and questions opened the door to real learning and creation for both me and my students. And working alongside them in that process is what makes my teaching feel vital, authentic, and important.

Resources

- Sean Harris, Nafis Pugh, Savon Goodman, Lynnae Edwards, Laborah Myles, Jordan Reese, and Oriana Principe. As Told by Teens. Unpublished play. Performed at National Constitution Center, Philadelphia. Jan. 24, 2012.

- Marsha Pincus. “Playing with the Possible: Teaching, Learning, and Drama on the Second Stage,” Going Public with Our Teaching: An Anthology of Practice. Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, 2005.