Children Who Made a Difference

Following are some of the children and events referred to in the article, “From Snarling Dogs to Bloody Sunday.” They are just a few of the many children and youth involved in the Civil Rights Movement.

Emmett Till

Emmett Till’s death is referred to as the “spark that set the movement on fire.” Emmett was 14 when he traveled from Chicago to Mississippi in 1955 to visit his cousin. Ignorant of the social protocol of the South, he made an off-hand comment to a white woman working in a store owned by her husband. Till’s body was found three days later. An all-white jury acquitted the husband and his brother, who later admitted to a reporter that they beat Till, shot him in the head, and threw his body in the river. Emmett’s mother, Mamie Till, had an open-casket funeral, to alert the nation to the racial violence in the South, and the media extensively covered his death.

The Little Rock Nine

Following the 1954 U.S. Supreme Court decision declaring “separate but equal” schools unconstitutional, school officials at Central High School in Little Rock, AR, decided to integrate, admitting a small number of Black students in 1957. The nine students who enrolled faced angry mobs, as well as the National Guard, who had been appointed by Governor Orval Faubus to keep the students out. Federal troops were sent to safeguard the students’ entry into the school, but still the students faced continued harassment from their white classmates.

Ruby Bridges

In 1960, New Orleans schools were ordered to follow the US Supreme Court mandate and desegregate. One Black six-year-old girl, Ruby Bridges, was sent on her own to desegregate William Frantz Elementary School. She faced angry mobs and had no help from city and state police. As in Little Rock, Federal marshals were sent to protect her. She was taught alone in an empty classroom, since white parents had pulled their children out of the school to protest integration. Later in the year, two children came back to the school. Slowly, through Ruby’s bravery and persistence, the school became integrated.

Sheyann Webb

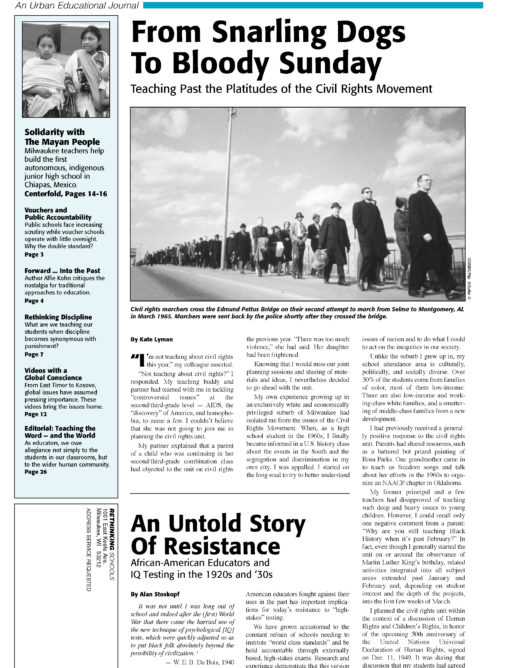

Eight-year-old Sheyann Webb and her friend Rachel West became the youngest participants in the voting rights movement in Selma, AL, in 1965. In Selma, fewer than 200 of 15,000 black people were registered to vote because of physical intimidation or discriminatory tests given at the voter registration site. Despite her parents’ fears, Sheyann participated in marches and rallies held to increase voter registration. One such march included teachers, junior high school students, and some younger students. These actions were met with violence, including the murder of Jimmie Lee Jackson. To protest Jackson’s death, and to further promote voting rights, the leaders planned a march from Selma to Montgomery on March 7, 1965. At the Edmund Pettus Bridge heading out of Selma, the marchers, including Sheyann, were met by local and state police officers with sticks, electric cattle prods, and tear gas. This day became known as “Bloody Sunday.” Beaten and temporarily defeated, the marchers retreated. A second march, of about 4,000 people, successfully reached Montgomery.

The Children’s Crusade

Since 1960, Civil Rights activists had been working to end segregation in public facilities in Birmingham, AL. Their gatherings were regularly disrupted by the Ku Klux Klan, who used beatings and bombings to discourage organizing. In May of 1963, James Bevel, an organizer with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, decided on the controversial plan of involving high school students in the protests and training them in nonviolent direct action. The high school students were soon joined by younger children, thousands of whom marched in the streets of Birmingham. Bull Connor, the Birmingham police chief, responded to the children by sending in officers brandishing clubs, police dogs, and water hoses. The violence toward the children was shown on national news.

![]()

![]()