Black Boys in White Spaces

One Mom’s Reflection

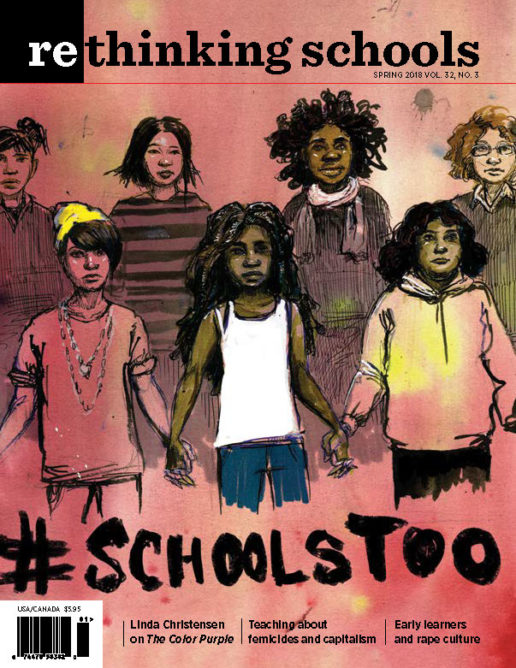

Illustrator: Erin Robinson

Erin Robinson

Right away I recognized her. Ruby Bridges. The courageous girl who defied white racists and became the first to integrate an all-white elementary school. My 7-year-old son pulled a handout out of his backpack with her face on it. He is in a bilingual, two-way immersion program at our local elementary school. As is our custom on Friday, we emptied his backpack and sorted the contents. We determined what needed to be recycled, what would be hung on our whiteboard, and what needed to be stored in my Things-to-take-care-of box by the fridge. I smiled, because as a former history teacher and lover of Black history, I was happy to see my son learning about this important historical moment. And then, I took a closer look and saw that it was in Spanish. I was elated as it dawned on me that my son truly is emergent bilingual. “Caleb, what’s this about? Did you read this in school?”

“Oh, yes. Her name was Ruby Bridges and they wouldn’t allow her to go to school with the white people.”

“That’s so cool that you learned about her. I learned about her too.”

“Yes, but Mama, I shouldn’t have been there that day.”

I frowned and looked him in his eyes “Why not? What do you mean?”

“Everyone stared at me when we read it because I’m the only Black kid in my class.”

“Oh sweetie. I’m so sorry. What did the teacher do? What did she say?”

“Nothing.”

“Did anybody say anything to you?”

“No, they just stared at me. I didn’t like it.”

I didn’t know what to say. My eyes welled up with tears. I put my arm around him as I tried to figure out what reaction would best serve him. Should I show him my anger? Do I simply weep and say nothing? Should I offer him a snack and ignore it altogether?

I was so disappointed in my lack of words and that I didn’t know what to do in that moment. It wasn’t a secret to Caleb that we’re Black and that on some level that makes us different from most of the people around us. We attend a white church. We live in a white neighborhood. We shop in white stores. And even though his bilingual class is 40 to 50 percent Latino, most of their faces are white or light-skinned. So far, I haven’t had any planned conversations about race with my boys. Not sure what I’m waiting for or even that I am waiting. Race is funny that way. As a reality, it’s ever present; as a topic it slips in and out of our lives, attaching to everyday things like hair and clothes, to speaking, to how my boys comport themselves in a grocery store. And like many difficult topics about life, the explicit conversations and lessons often come in reactionary waves.

Once I was really angry with both of my sons. Can’t remember what it was exactly but I remember having this colossal adult tantrum yelling at them about not listening to me. Through tears I shouted, “Don’t you get it? Do you think these white people are going to care that you’re good kids or that I love you? They will shoot you without even thinking!”

Then there was the time that Caleb came home and reported that two kids were making fun of his skin color in the lunchroom. Teasing him that he must eat a lot of chocolate and that’s why his skin is black. As soon as my son told me, I ran upstairs and emailed his teacher:

Caleb came home today and told me that Santiago and Matt were teasing him about being Black. Santiago and he seem to have had trouble all year long. I haven’t said anything to you because I was encouraging Caleb to learn to problem-solve and to speak up for himself but clearly it hasn’t worked and this time it’s gone too far. It happened in the lunchroom and Caleb said he raised his hand to tell the teacher but she never called on him. I asked Caleb to talk to you about it tomorrow. It has been tough being the only Black kid in his class. I am trying to prepare him for this life since he lives in Oregon and this will be a regular occurrence. But I also want others to be accountable for their actions. If you could please check in with the boys about this and let me know what you find out and decide to do, I would really appreciate it.

Turns out the kid who “said it first” was from a different class. Caleb’s teacher followed up with the boys to find this out and spoke to the other teacher, who subsequently had a class meeting. I don’t know the details of this meeting but am glad she acted. She also spoke with Santiago and two other kids who were there when it happened. I applaud her for not letting this go and dismissing it as “boys will be boys,” or “good-natured teasing,” or “I’m sure they were just joking around.” All of which are responses I have heard over the years.

So yes, race is not a stranger to us and we talk about it. But in this moment, with my little boy expressing his sadness and feeling invisible yet overly seen, I was speechless. And then I was sad. And then I was angry.

Here’s what I wished would have happened instead.

I wish Caleb’s response to my enthusiasm about him learning a moment in Black history would have been him saying, in his own excited voice, “And you know what else we learned? We learned that even though there were white people who didn’t want Ruby Bridges in that school, there were some who did.” I wish his teacher told him about allies, about the various people of all races committing to stand up against injustice. I wish the teacher noticed everyone staring at my son. I wish that she would have explicitly prepared the class for an age-appropriate conversation about difference.

I wish I felt comfortable asking him my customary “And how did that make you feel?” But I was afraid of his response. And my reaction.

If the teacher had been more thoughtful about the implementation of the lesson, maybe his answer would have been that he felt good. Maybe he would have felt validated if she had talked with him prior to the lesson and explained that sometimes when we’re the only one, it can feel lonely and embarrassing, but she was there. That she cared about him. That she would protect him.

Don’t misunderstand me. This teacher is thoughtful and definitely cares about my son. But she was not skillful in this circumstance. Part of me wants to be quick to forgive. Here I was, also not knowing what to do. Is it OK for me to criticize the actions of a teacher who has too many students and has perhaps been undertrained in how race mediates teaching and learning?

I choose to forgive her.

But I will also hold her accountable for the learning that took place that day. And the learning that should have taken place.

I wish that later that evening, when he was in bed closing his eyes to sleep, he was fantasizing about wildly unrealistic adventures he and his brother would have with the Six Million Dollar Man, how maybe they’d be social justice superheroes righting the wrongs of racism. He could have imagined what he’d do the next day, what he’d get to eat for snack, or if he’d be able to go over Uncle Kevin’s house and play on his old Wii. But instead, I have a feeling that he thought about how he didn’t want to go to school the next day. How he “shouldn’t have been there.”

I want Nehemiah and Caleb, my Black sons, to be free to dream, to go to bed with nothing on their minds but how much they are loved and cared for. Black boys deserve to be boys — to be young, carefree, and nurtured. To be seen as human — capable of being hurt, bullied, and afraid. They deserve a school system that will educate them with intentional love. They deserve teachers who will hold the learning space as sacred in all aspects and think through who their students are as they plan lessons and activities. We all deserve schools that will think about how race plays with learning — everyone’s learning. White students, especially, deserve to have teachers who will empower them as white allies.

Every neighbor, every teacher, all of the church members and friends of our family have a role in my boys’ development. As I think about the conversations I am having with my sons, I wonder what conversations white mothers are having with their sons and daughters. What are they saying — or not saying — that results in their children staring at someone who looks different from them, or teasing a Brown boy’s chocolate skin, or accent, or hair texture.

When I asked Caleb how his day went, at some point he answered, “I shouldn’t have been there that day.” The truth is, son, no one should have been there. No student — Latinx, white, or Black — was served well that day. At the same time, he should have been there; I just wish he was better served and felt like he belonged.

Dyan Watson, an editor for Rethinking Schools, is an associate professor in teacher education at the Lewis & Clark Graduate School of Education and Counseling. She is also co-editor of Rhythm and Resistance: Teaching Poetry for Social Justice and Teaching for Black Lives, from which this article is excerpted.