Seattle Test Boycott: Our Destination Is Not on the MAP

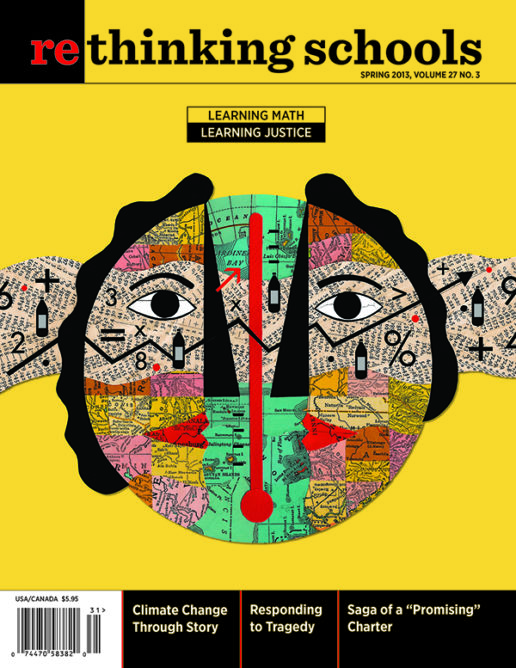

Illustrator: Noam Gundle

Seattle Education Association teachers gather to support the MAP test boycott.

On Jan. 10, 2013, we teachers at Garfield High School called a press conference to announce our intention to refuse to administer the Seattle Public School’s mandated Measures of Academic Progress (MAP) test—a computerized standardized test given up to three times a year. We made it clear that we are not opposed to demonstrating student learning, but the MAP test is so irrevocably flawed that it is not a useful assessment.

Our declaration of resistance, ratified by a unanimous vote at a staff meeting, sent school district officials scrambling for talking points and the PR flacks for the testing companies working overtime writing op-eds. Meanwhile, Garfield parents and students united with the teachers, with unanimous votes by the PTSA board and the student government in favor of boycotting the test. Schools around Seattle sent letters of support, as did the University of Washington’s faculty association. Large numbers of teachers at four other Seattle schools—Orca K–8 School, Center School, Ballard High, and Chief Sealth International High—joined the boycott.

Garfield’s original resolution cited many serious objections to the MAP test, including:

- The test is not valid at the high school level because the margin of error is higher than the expected gains.

- The test is not aligned to our curriculum.

- The former superintendent, the late Maria Goodloe-Johnson, brought the MAP to Seattle at a cost of some $4 million while she was serving on the board of the Northwest Evaluation Association (NWEA), the company that sells it. She did not disclose this connection until after the district approved the contract.

- The MAP test especially hurts students receiving extra academic support—English language learners and those enrolled in special education. These are the children who lose the most each time they waste five hours on the test.

- Our computer labs are commandeered for weeks when the MAP test is administered, so students working on research projects can’t get near them. The students without home computers—predominantly low-income and students of color—are hurt the most.

- Although not designed to do so, the MAP test is used in evaluating teachers.

Washington ranks number 1 in the nation in the number of standardized tests K-12 students take. The state spends more than $100 million on standardized tests, yet ranks 42nd in per pupil spending. These are the intolerable conditions that provoked educators in Seattle to put their livelihoods on the line.

Garfield’s stand against the MAP test didn’t originate as a stand against standardized testing in general. But, as people around the nation saw the issues that Garfield’s teachers raised, many saw similar flaws in the mandated tests in their own schools. The story of how we organized the test boycott in Seattle holds lessons for people everywhere who want to liberate education from the standardized testing regime.

Organizing the Vote

One afternoon in December, I got a phone call from a longtime teacher in our building. Because I am a union representative at Garfield, I assumed this was another inquiry about our collective bargaining agreement. But when I got to the teacher’s cubicle, she peered over the top of the worn partition to make sure no one was within earshot.

“I’m not going to give the MAP test,” she said with a delighted defiance. “And there are others I have talked to as well.”

Teachers had been complaining of the many flaws of the MAP test for years—including by resolution at a citywide union meeting in 2010—but now it seemed Garfield teachers were ready to take action. We organized meetings of teachers in the tested subjects—reading and mathematics—to see what action they might be prepared to take.

Once we had heard from all the teachers in the tested subjects, we brought up the question of a MAP boycott at an all-staff meeting. Teachers asked me what the consequences could be. I didn’t sugarcoat it: “If you refuse a directive you can be labeled ‘insubordinate.’ We have a progressive discipline policy in the Seattle public schools, but ultimately your job could be on the line. However, if we all refuse to give the test, I would be surprised if they fire anyone.”

A highly respected teacher rose and addressed the room: “This flawed test is going to label my students and me as failures because it isn’t testing what I am teaching. I would rather be reprimanded for standing up for what I believe in than for sitting back and letting this test take advantage of me and my students.”

That was it. A unanimous vote to boycott the MAP test followed.

Solidarity

The first test of our resolve came when Superintendent Jose Banda sent an e-mail to every teacher in the district declaring that the MAP test was not optional, and he expected everyone to perform their assigned duties. More than one teacher wondered if we had made the right decision. But, within minutes, the office secretary came on the intercom to announce that a pizza lunch, sent by supporting teachers at a school in Florida, was being served in the conference room. Our resolve grew as the chocolates, flowers, cards, books, donations, e-mails, and resolutions of support came streaming in from around the country.

The boycotting schools called for a national day of action to support the boycott on Feb. 6, and we were overwhelmed by international solidarity. We heard from parents, teachers, students, and community members in Victoria, British Columbia; Austin, Texas; Oxfordshire, England; and Rochester, New York. Students in Portland, Oregon, initiated their own boycott of the standardized OAKS test.

Before our first sit-down meeting with Banda, the district announced that teachers in tested subjects could face a 10-day suspension without pay for failure to administer the test. When these bullying tactics only strengthened the teachers’ determination, Banda issued a new directive, mandating that Garfield’s administration oversee the MAP test if teachers wouldn’t cooperate—an attack designed to turn Garfield’s teachers against our administration. It didn’t work. Teachers maintained their focus on the problems with the school district. Students passed out fliers urging their peers to opt-out. Parents rose to the challenge and mobilized an opt-out campaign, resulting in 75 percent of our 9th graders carrying notes to school exempting them from the MAP; of the remainder, most blasted through the computer screen questions in only a few minutes, invalidating their scores.

What Replaces Standardized Tests?

Our MAP test boycott has already achieved several important victories. The national mobilizations, petitions, and e-mail campaigns helped convince Banda to backtrack on his suspension threat. Very few students at Garfield ended up taking the MAP test this winter, which resulted in more instructional time. Because we dramatically reduced testing, our libraries were liberated for their intended use.

However, our struggle has just begun. Banda has vowed there will still be “consequences” for our boycott. In the spring we face the third and final round of MAP testing for the year—the scores that the district wants to use to measure teacher effectiveness. This will require another major mobilization.

For the boycotting schools, our biggest challenge will be collaborating to design an alternative to the MAP test. As you would expect, there is a range of opinions among the boycotters about what should replace the MAP. Some of my colleagues propose replacing the MAP with another test that is aligned to our curriculum. Others, myself included, believe that portfolios and performance-based assessments would be better because they are more directly tied to the curriculum of specific teachers, can help cultivate skills and talents not measured by a standardized test, and allow for the assessment of students over time, rather than on a random day.

Garfield’s teachers and the other MAP test boycotters have made a public declaration that we will no longer be relegated to the margins of the discussion about how to improve our schools. The current system is increasingly designed to reproduce the inequities in society, but teachers, parents, and students in Seattle are redesigning it. Join us.