Lesson Plan

Eyes on the Prize: ‘Fighting Back: 1957-1962 '

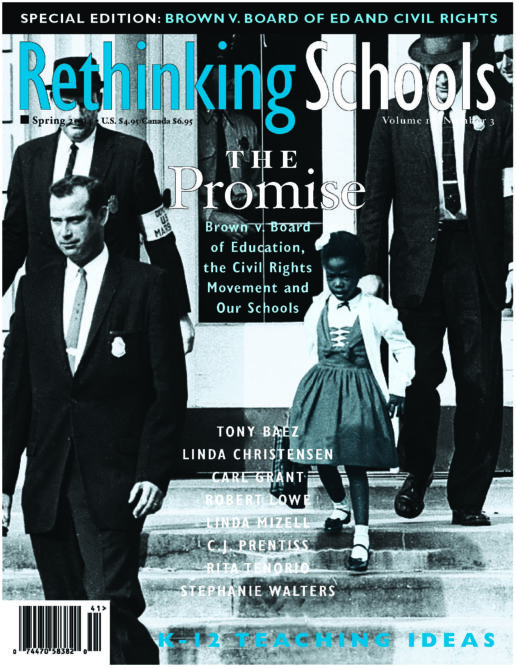

Whites harass Elizabeth Eckford,one of nine African-American students whose admission to Little Rock ‘s Central High School was ordered by a federal court.

I built this lesson around the struggle to desegregate schools in the South, as dramatically retold in the video “Eyes on the Prize: Fighting Back: 1957-62,” which focuses especially on Central High School in Little Rock, Ark., and the University of Mississippi in Oxford. My aim is to enlist students in empathizing with some of the protagonists of this movement.

Almost 50 years after nine students were escorted to Little Rock’s Central High School by heavily armed federal troops, it’s easy to scoff at the results of desegregation. So black children can go to public schools formerly reserved for whites. So what? Is life within integrated schools equitably structured? Has desegregation significantly reduced the achievement gap between black and white children? Have income disparities withered away? Can we even say that schools are less segregated than they were 50 years ago?

This is not a lesson that attempts to analyze the ambiguous legacy of desegregation. Instead it seeks to celebrate the determination and sacrifice of those individuals who were the shock troops in this struggle. And, to a lesser extent, it attempts to examine some of the resistance to school integration. Students watch the video, but through writing they are also invited to “become” the individuals whose lives shaped and were shaped by these key civil rights battles.

Materials Needed

Video: “Eyes on the Prize: Fighting Back: 1957-62;” Optional: copies of Student Handout 1: “Inside Elizabeth Ann Eckford;” and Student Handout 2: “In Their Own Words: Eyes on the Prize: Little Rock and Mississippi.” (See sidebars, pages 54 and 55.)

Suggested Procedure

1. Explain to students that you’ll be asking them to do some writing based on the events depicted in the video they’re about to view. They’ll have the choice of writing interior monologues, stories, poems, dialogue (two-voice) poems, diary entries, or letters. Ask them to write down incidents during the video that they find especially sad, inspiring, or outrageous. They might write their impressions of particular characters or events. Urge them to “steal” lines from the narrator or people interviewed. They’ll be able to incorporate these in their writing.

2. Show the video. Over the years I’ve supervised a number of student teachers in Portland schools. It’s interesting to watch how some of them use video in the classroom. At least initially, their strategy is to wheel the VCR and television to the front of the classroom, turn it on, and go back to their desk to watch or grade papers. Needless to say, this does not always result in students’ rapt attention and full comprehension. I’m an interventionist when it comes to showing videos. Particularly with documentaries, which often require more context setting, I sit by the television and stop it frequently to ask a question or point something out. I may rewind it to replay someone’s comment or an especially poignant scene. At times, I stop it to ask students to wonder what might be going through a person’s mind at a particular point or to anticipate how an individual or group will resolve a dilemma. I try not to overdo it, and I have to confess that, at least at first, some students are annoyed by this practice. They have years of video-watching practice—staring at the screen—and don’t feel that they need someone butting in to ask questions and making them mentally “talk back” and evaluate underlying messages. Generally, we reach a kind of negotiated middle ground—somewhere between their desire to be left alone to enjoy or “veg out” and my desire to ask them to think about every last nuance.

3. Stop the video immediately after Elizabeth Eckford (one of the nine students chosen to desegregate Little Rock’s Central High School) gets on the bus. Read aloud the dramatic account excerpted from NAACP leader Daisy Bates’s The Long Shadow of Little Rock, included on page 54 as Student Handout 1, “Inside Elizabeth Ann Eckford.”

4. Resume the video.

5. Questions for discussion afterwards:

- The narrator in the video comments that because other forms of integration had been successful in Little Rock, some people hoped that the same would be true for school integration. Why wasn’t this the case?

- Why did President Eisenhower not act sooner to force Governor Faubus to allow the nine students into Central High School?

- Eisenhower sends in the troops to protect the Little Rock Nine. The narrator of the video comments, “The troops did not, however, mean the end of harassment; it meant the declaration of war.” Who were the sides in this war? What were they fighting for?

- Melba Pattillo Beals describes how she was tripped and fell onto broken glass. Why did the black students put up with all the abuse? Why not just say, “Forget it. I’m leaving”?

- Look at the comments by the white student about Spanish and Chinese people on the “In Their Own Words” handout. When she declares that Negroes are “more different” than Spanish people, what do you think she’s referring to?

- Why does Melba burn her books?

- Constance Baker Motley says that the civil rights struggles in the South created a “genuine revolution on the part of black people.” Do you agree? How do you define “revolution”? What were the aims of this revolution?

- Analyze the Ross Barnett quote from his speech at the Mississippi-Kentucky football game. Who are the “people” he refers to? What are their “customs” and “heritage”?

- The reporter asks James Meredith if he felt guilty for the deaths at Ole Miss. Should Meredith have felt guilty? If Meredith hadn’t been so diplomatic, how might he have responded?

6. Ask students to write from the video. One option is to postpone a discussion of the video until after students have written, and then to incorporate the above questions into a discussion that grows out of the writing. Allow students to choose how they’d like to respond to the video: interior monologues, stories, poems, dialogue poems, diary entries, or letters. Brainstorm possible topics with students. For example, they might write as James Meredith when the reporter asks him if he feels guilty; as Ernest Green when he walks across the stage to accept his diploma; as Melba watching her books burn; as Minnie Jean when she dumps chili on the head of the white boy who harassed her; as the all-black cafeteria workers watching and applauding. Students could write dialogue poems from the standpoint of black and white students in Central High School :

I am a student

I am a student . . .

Or students could write dialogue poems from the standpoints of white and black reporters about any of the events depicted in the video.[For examples of dialogue poems, see “Two Women” in Rethinking Our Classrooms, Vol. 1, or “Two Young Women” in Rethinking Globalization.]

List students’ writing ideas on the board. Encourage them to choose the form of writing that will best allow them to explore the emotions and ideas they had during the video. I always make sure to give students time to begin—if not finish—the writing in class, as I find that this results in my getting more and better quality papers.

7. Seat students in a circle and invite them to share their pieces in a read-around. Ask them to be alert to common themes in their writing. In my classes, some students focus on the hardships of the African-American teenagers attempting to integrate Central High School, as does Lila Johnson in her poem:

I remember the mob

how faces became blurred shades

of light and dark

how fingers reached greedily for

a sleeve an arm a neck

how bodies formed

an intricate weave

and squeezed

in hopes of crushing

a young black girl

Frequently, students write from Melba Pattillo’s standpoint [see Linda Christensen’s article, page 48] as she burns her books after that 1957-58 school year. Sarah Sherwood penned a bitter piece she called “The Fire in My Soul”:

I swore to myself I would never go back there again, that I would never put myself through that kind of humiliation again. I hated them; I hated them for making me hate. I told myself I would never become like them, but here I am wishing they were all dead.

And then she lights her books on fire:

I sat there and watched as my dreams, my hopes, burned away. I coldly stared at the flame. There were no more tears to cry.

Despite the anguish in students’ writing, perhaps the most common motif in their pieces is defiance. Alice Ramos imagines the thoughts of Ernest Green, the first African American to graduate from Central High School:

But I graduated from

your all-white, all-prejudice schoolThey didn’t clap

When I went to pick up my diplomaBut I didn’t care

I don’t need their clappingI beat the monster

that day I stepped inside the school.

In fact, 50 years after Brown, we can see that the “monster” is more multi-faceted, more complicated than it may have appeared to the NAACP activists who led the move to integrate Little Rock’s Central High School. So we need to help our students reflect on alternatives that civil rights activists might have pursued 50 years ago, and let’s also help them probe the contemporary nature of the monster of racial inequality.

But we should offer students the opportunity to celebrate the courage and tenacity of the young people who risked their lives for a better education—for themselves and for those who would come after.