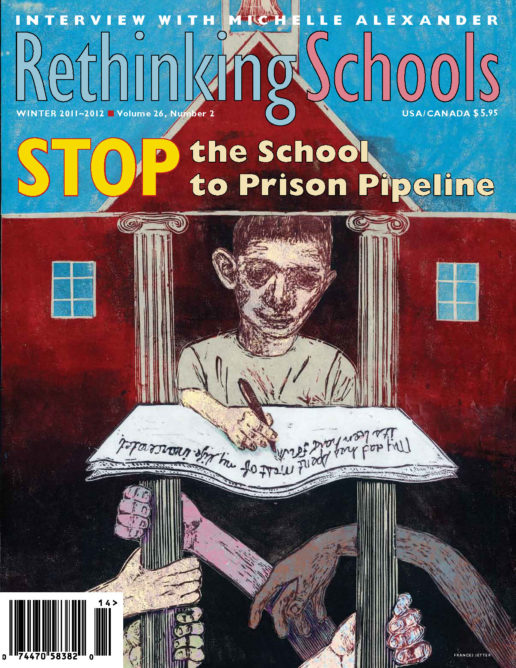

The Classroom to Prison Pipeline

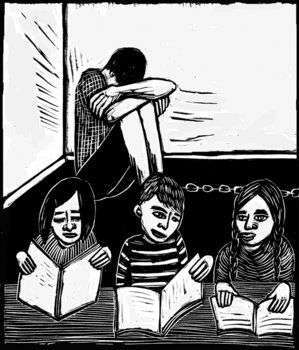

Illustrator: Meredith Stern

The school-to-prison pipeline starts in the classroom. I know. During 4th-period English, I came dangerously close to becoming the teacher who pushes students out of class into the halls, into the arms of the school dean, and out into the streets. I understand the thin line teachers tread between creating safe classrooms and creating push-out zones.

It started harmlessly enough. This September I returned as a volunteer to the school where I taught for more than two decades to co-teach junior English with a fabulous teacher, Dianne Leahy. Forty students are stuffed into our classroom. The school district instituted another new schedule to save money, so we only see our students every other day for 90 minutes. A few weeks into the school year, and I was still confusing Ana and Maria, Deven and Terrell, and Melissa and Erika. Daily it took so long to settle the students down that Dianne and I were exasperated by how little real work students completed. We battled competition with cell phones and side talking, as well as frequent interruptions due to students strolling into and out of the classroom or plugging in their cell phones or iPods while we attempted to demonstrate a writing strategy. In addition to the lack of forward movement on reading and writing during the day, students did not complete their homework. Embarrassed by their behavior and their skimpy work, I hoped that no one would walk in and see us totally at the mercy of these 16- and 17-year-olds.

We tried to build relationships. Dianne found out what sports kids played, who danced, who was a cheerleader, who loved skateboarding. I watched her kneel in front of kids as she passed out folders with a word of praise or a question that demonstrated she cared about them as individuals. Because I was out of the class during the opening days of the year, I followed her lead, attempting to connect names to faces and faces to aspirations.

While out on a hike after a particularly frustrating day, I remembered a former student, Sekou, who returned from Morehouse College with a story about a ritual that he participated in during the early days of his freshman year. I thought Dianne and I needed a ritual to help students remember that the classroom is a sacred place of learning. Eager to create community out of the chaos, I prepared a document for students to sign that promised they would complete their work, refrain from using cell phones, and participate fully in class by respectfully listening to others. Now, even as I write this list, it doesn’t sound too farfetched. In fact, it sounds like what school is about. My huge mistake was asking them to sign the paper—and to participate in a ritual where we walked back into the classroom saying, “I am a scholar.” Who did I think I was—Michelle Pfeiffer from Dangerous Minds?

I brought the document to class and distributed it to students. They accepted the first bullet—do your work—but when we got to cell phones, Sierra said, “I’m not signing. I text during class, and it doesn’t interfere with my work.”

Her voice brought a flood of others. Melanie said, “I’m not signing. I already do my work.” Ursula seconded that. Vince agreed. Then Jasmine said, “I only pledge with God.” Kevin gave her a high five, and several others laughed and wadded up the paper. I’m not sure if it was Jason or Victor who said, “Let’s all not sign. What can they do? They can’t kick all of us out of class.”

I had a moment of pure panic. Ten minutes into a 90-minute period, and I had a revolt on my hands. Part of me was horrified as I watched the class coalesce into one angry swarm, and part of me thought, “Hot damn. We have a class of activists.” This is the point at which my 30-plus years in the classroom and my memory of other hard years helped me weather the moment. I could have sent Victor, Sierra, and others to the dean’s office with referrals for insubordination, beginning an out-of-control relationship that would teeter between their defiance and my desire to control the classroom. When the class chaos tips a teacher to institute measures that tighten the reins by moving defiant students out of class and sending them to the disciplinarian (which moves them one step closer to the streets), she’s lost the class.

As classroom teachers we wield an enormous amount of power to control students’ destiny. Dianne and I are determined to keep all of these students in junior English, but it is conceivable that a teacher with 40 students might want to cut a few, especially those who resist. Because we have taught for many years, we know that we will win most students over, but this experience made me wonder about the new teacher down the hall who doesn’t have that history of a beautiful June classroom community to recall.

The tide turned when one of the football players said, “I want to play Grant on Friday night, so I’m signing.” A number of other students followed suit. They even walked out of the classroom and returned saying, “I am a scholar.” They didn’t go through the arch of hands I had in envisioned, nor did they say it like they believed it, but we did make it through the class, although students looked at me like I was a rattlesnake for the rest of the day.

This incredibly misguided move on my part reminded me that students need to be engaged in meaningful curriculum and to develop relationships with their teachers and each other. There is no short cut to making that happen. Although I might believe that they are brilliant, in that moment I was a white woman in a community of color taking away students’ perceived rights and treating them disrespectfully. And although both Dianne and I returned to this school because we love the kids it houses, the students didn’t know us, and didn’t have any history with us that would ease the slide into the new year.

The night of my fiasco I looked back over the students’ records. Two of the 40 had passed the state reading and writing test given the previous year—tests they now need to graduate. Only 15 of the 40 are on schedule to get their diploma on time; the others have failed two or more classes. These students were primed to revolt. They carry failure like a dirty rag behind them, and our opening acts had been all about rigor and improving their skills, not about developing a relationship that valued them and made them feel competent.

In these days of record unemployment, when parents are losing jobs as well as homes, and few have resources for college, we need to create a curriculum that demonstrates an interest and understanding of our students’ heritage by studying their history or literature or language or statistics that touch on their lives. The curriculum needs to acknowledge that their lives are important and worth studying. The fact that they come to school when they’ve experienced so much failure and when the future seems so bleak is in itself a heroic act.

While we weren’t studying Hawthorne or Emerson, we hadn’t created a curriculum that made them feel successful, significant, or curious. And a curriculum must do that, especially in marginalized communities where students experience the oppressive conditions of being over-policed. Classwork needs to be about big, important ideas and connected to their lives.

Curriculum and the Pipeline

Partially, fear of students failing to pass the tests fueled our opening days. We created an alternative reading work sample out of Sherman Alexie’s excellent essay, “Why the Best Kids Books Are Written in Blood” (Fall 2011 Rethinking Schools), so we could ascertain students’ reading ability. But students didn’t engage, and because we wanted a clean read of their abilities, we hadn’t primed the pump enough to excite them about reading the essay—a warm-up for our first book of the year.

In our defense, we chose that first book, Sherman Alexie’s screenplay Smoke Signals, to create links to students’ lives as well as curiosity. In the beginning, they weren’t connecting to it. That changed when we started discussing the alcoholism and the father/son relationship in the book. Terrell talked about how Arnold, the father, was an alcoholic asshole. His frank assessment broke the ice. Others jumped in. They hated it when Arnold hit Victor, his son, just because he dropped his father’s beer. Uriah talked about how Arnold used alcohol to wash away his guilt for burning Thomas’ parents in a house fire.

Although the discussion was short and some students still side talked, the class talk marked the first movement toward compelling work. But the turning point came when we asked students to write a forgiveness poem. (See Reading, Writing, and Rising Up, p.66) In this lesson, students read Lucille Clifton’s “forgiving my father” and two student samples—one by a student who forgives her mother for moving so much and creating disruptions in her life, and one by a student who doesn’t forgive his father’s absence from his life. Our students actually stopped talking and listened to the poems. Then we said, “Write a list of who you want to forgive or not forgive. Then choose one to write about. If you don’t want to write about your life, you can write a poem from Victor’s point of view in the book.”

Students wrote, silently, mostly. They wrote in the classroom, on the stairs in the hallway, sprawled out against the lockers in front of our class. They wrote furiously. At times, they crept close to a friend and handed their paper over. At the end of the period, students got up on the stage Dianne built for her room and shared their poems. Students cried together as they shared their poetry, written to absent fathers, to dead grandparents, to themselves. That was a Thursday. The following Monday, they returned to class and wanted to share more. Trevon caught me in the hall, “Are we going to share our poems in class? I want to hear everyone’s.”

Although Dianne and I still struggle, that poem cracked the class. But that’s what curriculum that puts students’ lives at the center does. It tells students that they matter, that the pain and the joy in their lives can be part of the curriculum.

The school-to-prison pipeline doesn’t just begin with cops in the hallways and zero tolerance discipline policies. It begins when we fail to create a curriculum and a pedagogy that connects with students, that takes them seriously as intellectuals, that lets students know we care about them, that gives them the chance to channel their pain and defiance in productive ways. Making sure that we opt out of the classroom-to-prison pipeline will look and feel different in every subject and with every group of students. But the classroom will share certain features: It will take the time to build relationships, and it will say, “You matter. Your culture matters. You belong here.”