When a Picture Book Is Subversive

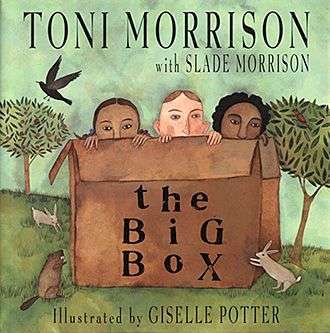

As a K-8 teacher librarian, I love to read picture books that generate thoughtful questions and debate among the diverse students I work with. Toni Morrison’s children’s book The Big Box is just such a gem. Over the years, I have read this book to countless groups of children in the classroom and the library, and I am struck every time by how fascinated they are by the story. There is so much to talk about with The Big Box; it is a challenging, complex book, but told simply in rhyme and whimsically illustrated by Giselle Potter.

At its core, The Big Box is about freedom. Three children—Patty, Mickey, and Liza Sue—live together inside a large brown box. The box is like a house—with carpet, beanbag chairs, and fancy beds—but the door is sealed with three big locks. The various grown-ups in the story, who range from teachers to neighbors to parents, explain the situation through a repeated refrain: “Those kids can’t handle their freedom.” And, although the children receive extravagant gifts during their parents’ weekly visits to the box, they yearn most of all for their freedom.

There are many references to the wildness outside, but the windows in the box are shuttered. On special occasions the children receive tokens of the natural world: a butterfly under glass, a picture of the sky, and a jar of “genuine dirt.” But most of their gifts are commercially produced items such as Legos, Nikes, and Pepsi. The freedom of the wild animals outside to scream, hop, and chew trees “when they need to” is in stark contrast to the limitations of the kids stuck inside.

We learn a little about each child: Patty used to live in a regular house but wouldn’t play with dolls or recite the Pledge of Allegiance correctly. Mickey, an apartment dweller, had too much fun in the street and disobeyed posted signs. And Liza Sue, from a farmhouse in the country, “let the chickens keep their eggs” and allowed squirrels to eat the fruit in the orchard. In each case, the children “made the grown-ups nervous” by not following established rules, although they brushed their teeth, ate beets, and vacuumed the rugs. The children proclaim: “If freedom is handled just your way, then it’s not my freedom or free.” In the last illustration, we see the children climbing out of the box, the walls coming apart, the wild animals welcoming them back outside.

I was dismayed to learn recently that The Big Box is out of print, so I did some research to find out why. An extraordinary children’s book by someone who won the Nobel Prize for Literature should be a keeper. I learned that Toni Morrison’s son Slade was once told by a teacher that he couldn’t handle his freedom, which inspired his mother to create the rhyme years later. But, according to Morrison, it was not easy to get the book published. As one publisher told her: “We don’t publish books in which the child at the end is not reconciled with the adult point of view.”

Morrison certainly spins a thought-provoking, uneasy tale about challenging societal norms and standing up for freedom; this is precisely what makes The Big Box so engaging. It saddens me to think that a children’s book like this may be unpublishable in today’s ultra-profit-driven world. Fortunately, public and school libraries acquired The Big Box before it disappeared from bookstores, and I found several sources on the internet.

Recently, teachers at my school were writing opinion pieces with students. I thought immediately of The Big Box and found it for them on the library shelves. Patty, Mickey, and Liza Sue are sure to engage readers and spark conversation in the classroom and beyond.