Warriors Don’t Cry: Acting for Justice

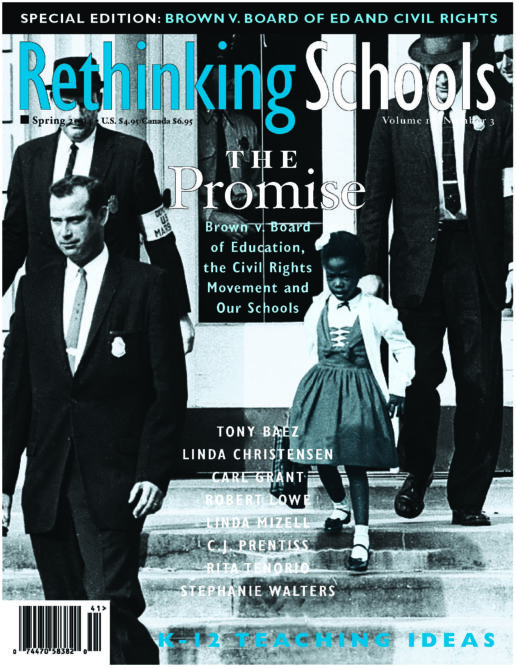

Police lead a group of African-American school children off to jail following their arrest for protesting against racial discrimination in Birmingham, Alabama, May 4,1963.

We must teach students how to navigate in an unjust world, but also teach them how to change it. Educators talk about teaching the basics—reading, writing, and math—but shouldn’t teaching students how to stand up, fight back, and work for justice be mandatory curriculum for a democratic society?

Many of our students experience injustice daily—critical remarks about their weight, facial features, hair, or clothes. Frequently students and their families are targeted because of their race, language, class, or religion. They are denied housing, jobs, fair wages, health care, and decent education. Part of students’ literacy education must be to read that inequality and resist it.

What we teach and how we teach either endorses these injustices or disrupts them. The injustice that our students may experience at a personal level often has social roots. For example, Warriors Don’t Cry tells the story of Melba Pattillo Beals’ days as one of the Little Rock Nine, the students who struggled to integrate Central High School in Arkansas. The story is an insider’s view of how nine teenagers fought to change a segregated, unequal school system in Little Rock and how the students at the high school and the whites in the community resisted desegregation. Melba’s story is a personal account that raises the larger social issue of educational inequality based on race and class. Teachers can bring stories like Melba’s into the classroom to give students role models of ordinary people who became extraordinary when they chose to act against the injustice they experienced. But we can also interrupt injustice by teaching students to stop silently enduring when they feel marginalized or disrespected.

I developed this “Acting for Justice” unit for students to practice behaving as allies and so they can see that at most points in history, people—especially the bystanders—have the power to reshape the course of events. Although this activity can stand alone, I use it when I teach Warriors Don’t Cry.

As students read the book, I ask them to keep track of people who act as allies for the Little Rock Nine as well as the different methods they use. [See ” Warriors Don’t Cry: Brown Comes to Little Rock” page 43.] And the students do—from the NAACP leaders who fought for integration through the courts; to Grace Lorch, who led Elizabeth Eckford to safety on the first day of integration; to Melba’s white classmate, Link, who called each night to let her know which halls to avoid and who helped her escape torture on numerous occasions.

Because I want to familiarize students with other strategies for social change, we also read an interview with James Farmer, one of the founders of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). In the interview, Farmer discusses some of CORE’s early activities in the 1940s using Gandhi’s nonviolent strategies to integrate Jack Spratt’s, a Chicago restaurant. (To see the interview, visit www.

core-online.org.) Students love the white customers who aren’t part of the sit-in, but who realize what is happening and act as spontaneous allies refusing to leave their seats or eat. They chuckle at the ingenuity of the allies’ answer when they, too, are asked to “eat and get out.”

They answer, “Well, madam, we don’t think it would be polite for us to begin eating our food before our friends here have also been served.” As we read the interview, I ask students to answer the restaurant personnel as if they are CORE members. “The restaurant says they will serve the blacks in the basement. How do you answer them?”

The students yell, “No. We won’t be served in the basement.”

I come back at them with the restaurant’s next proposal. “The restaurant says they will serve the blacks at the two booths in the back of the restaurant. How do you answer them?”

The students yell, “No. We won’t be served in the back of the restaurant.”

Creating Scenes

Once students have been steeped in historical and literary descriptions of ally behavior, I ask them to create a chart on their paper with four categories: Ally, Target, Perpetrator, and Bystander.

First, they categorize the historical/ literary characters from Warriors Don’t Cry: Link and Grandma India were allies, Melba was a target, many white students and teachers were perpetrators, Danny was both an ally and a bystander.

We read my former student Sarah Stucki’s story, “The Music Lesson” (see page 51), about Mr. Dunn, a music teacher who humiliated Mark Hubble, a Native-American student in class. Mark never returned to class—or school—after that incident. Because a student wrote the story, “The Music Lesson” provides a clear, accessible model. We return to the categories, and students discuss each character’s role in Sarah’s story. Once students are clear about the categories, I ask them to brainstorm a list from their own lives. When have they acted as allies? Were they ever targets? Perpetrators? Bystanders?

When I first started using this activity, I developed “scenes” for students to act out because I wanted to get at injustices that I wasn’t sure they would cover. Over the years, I discovered that it was far more powerful for students to write from their own experiences. When I taught this unit to a sophomore class, I was astounded at how many students confessed to being perpetrators, targets, and bystanders, and how few acted as allies. One student offered that he was a “jackass” in middle school and regularly tormented other students. Many talked about making fun of younger, weaker students. Sometimes their abuse was physical. Few students had stories of acting as allies. In our discussion, it was clear that students didn’t feel good about their participation or their lack of intervention, but they didn’t feel powerful enough to stop the racist, homophobic, or belittling behavior and comments.

After students make their lists, I encourage a handful of students to share their incidents. Mario, an African-American sophomore, talked about store clerks following him because they thought he might steal clothes. Adam, an African-American student, discussed how the counselor automatically placed him in a “regular” English class without checking his test scores. Michelle shared the story of acting as an ally for several special education students who were teased by a group of boys.

Once a few students share in the large group, I ask students to write the story of the injustice and encourage them to include a description of where the story took place, a description of the people involved, and the dialogue of what was said during the incident the way Sarah did in “The Music Lesson.” They might also include how they felt about the act and whether or not they were changed because of the discrimination.

After students write their first drafts, we return to Sarah’s story so they can practice rewriting history, by finding ways to act with those who are targets of injustice. I ask students to move into small groups and tell them, “You are all students in the choir room. You are witnessing this event. You have to figure out how you can keep Mark from leaving school. You have 10 minutes to come up with a plan. Talk with other groups as well. Think about the strategies we’ve learned from other activists.” After about 10 minutes, I ask for a volunteer to play Mark Hubble, the student. I play the teacher. We role play the scene from Sarah’s story. I single out Mark—the student volunteer—and ask him to come to the front of the room. Then students act for justice: Sometimes they all stand when I call Mark forward. Sometimes they start singing with Mark. Once they all got out of their desks and filed to the front of the room and stood beside him. Occasionally, a few groups have threatened to go to the administration and report me (Mr. Frye) for my abuse of Mark. We talk about which strategies would be most effective. I ask the stand-in for Mark to talk about which strategies he or she thought would keep him at school.

Once they understand how I want them to “rewrite for justice,” I divide students into small groups to share their stories. Power relations in the classroom get played out in small groups. The more popular or assertive students sometimes silence or rudely ignore their peers when they tell their stories. I’ve observed students file their nails, flip through a magazine, or complete an algebra assignment while one of their group members reads. Besides modeling how I want them to act, I create written tasks for students to perform while they listen to their classmates in order to break students of these “silencing” behaviors. After each story is read, students write on the following prompts to focus their attention on the storyteller:

- Explain what can be learned from the piece.

- Ask the writer questions to get more details.

- Share any similar experiences from your life.

- If no one intervened to stop the discrimination in real life, discuss how someone could have “acted for justice” in the incident.

Group members choose one story from their group to act out, then assign character roles and decide how to stage the story. Because this is an improvisation, they don’t need to write down lines, but I do encourage them to practice. I tell them to make sure at least one person in their group acts as an ally to interrupt the discriminatory behavior—even if that didn’t happen in real life. They can add details, characters, and props to make their scene come to life. Typically, students share and select a scene during one 50-minute period, then gather for about 15 to 20 minutes the next day to rehearse their scene.

Over the years, I’ve learned to be an advocate during this part of the activity. I circle the class listening to as many stories as I can. Sometimes the most forceful stories come from students who don’t have “power” in the classroom: limited English speakers, shy students, and chronic non-attending students.

Their stories might be pushed aside by more talkative or popular students if I don’t intervene. For example, one popular girl wanted to act out the story of how her best friend stole her boyfriend—not exactly the kind of “social injustice” story I had in mind. When I asked about the other stories, I discovered Sabine’s:

I came to this school as a ninth grader.

I didn’t arrive in the United States until August. I studied and practiced my English, but it wasn’t too good. I was afraid to come to school. In my P.E. class, girls made fun of me because I’m Muslim and I wear a scarf. They also made fun of my English. I would go home from school and cry. But one girl stood by me in class. She wouldn’t let the other students tease me.

I told the group that Sabine’s story would be a better improvisation. In other words, sometimes I intervene in the classroom on the behalf of the silenced.

After students have an opportunity to rehearse, I bring the large group back together and arrange the desks or chairs in “theater” style. Before we begin I say, “You might feel uncomfortable in your roles as you act as either people who discriminate or as the victims, and laughter is often a way that we release our discomfort; however, that doesn’t mean that we think discrimination is funny.”

Sharing Our Stories

As each group improvises its story, the rest of the class watches and takes notes to capture any great lines or words to use in the interior monologue they will write from one of the character’s points of view.

After each group presents its scene, students talk about the incident. Sometimes it helps for the “actors” to stay on stage, so that the audience can ask them questions, “How did you feel when Stella called you a name? What caused you to disrupt the injustice? How did you feel afterwards?” Jennifer Wiandt, a language arts teacher at Cleveland High School, added the question, “Who had power in the situation?” Students in her class discussed how older students, popular students, and teachers have power.

When Sabine’s group acted out her incident of injustice, I asked, “Who would have been Sabine’s ally in P.E.?” Two girls raised their hands. Then I asked, “Who would act as an ally now?” All of the students raised their hands.

After all groups have performed, I ask students to write interior monologues from the characters’ points of view. Students may write from the characters they portrayed or observed or from their own original stories.

As students read their monologues to the rest of the class, they often excavate the emotional territory these pieces triggered. How do people feel when they are laughed at? Excluded? How do they feel when they gather the courage to stand up for someone else, when they fight back against ignorance and hate? Why didn’t some of us act even when we felt immoral standing by as a witness to injustice? Who gets hurt? As I mentioned earlier, I was surprised at how many of my students shared instances when they tormented others. I was equally surprised at how few intervened to help when someone was hurt. But I also learned that students felt conflicted and unhappy about their role in hurting others.

One student, a biracial girl who hid her African-American identity from the class, told me in private that she cried after watching the cruelty of her classmates in middle school, but she was so afraid that they’d turn on her that she never helped anyone out. She was light enough to pass, and she’d heard friends tell jokes about African Americans, so she hid her racial heritage. “They had teased me about my facial hair. I was afraid that if I helped the boy they were teasing that they would remember my hair or find out I was part black and start laughing at me again.”

Students need the tools to confront injustice; they need to hear our approval that intervention is not only appropriate and acceptable, but heroic. Acting in solidarity with others is a learned habit. Elena, a sophomore, wrote about her experience tormenting a fellow student:

In a classroom of 32 fifth graders only one was singled out. His name was Lee. The only thing that made him different from the rest was the fact that he was smart, walked on the balls of his feet, wore a rat’s tail, and did a funny thing with his hands when he got happy . . . I’m sure if we could all go back in time none of us would make fun of his unique ways.

Was it the rat tail that singled him out or the fact we were all oblivious to people’s feelings? Or could it have been that we were all looking for a cheap laugh even if it was at someone’s expense?

Sure I admit it. I was one of those individuals who made fun of him. Worst of all, I was the one who did most of the nitpicking. I was the original class clown, the one who would get the class roaring. I made fun of him not to boost my self-esteem, but to get a cheap laugh. It was almost like a job to attend to.

By the time I realized this was an individual’s feelings I was juggling in my hands, it was too late. At this point he would break down on the first insult that came his way. The way the tears rolled down a 10-year-old boy’s face made me think twice about what I’d done. I backed off him after that, but when it came to other kids making fun of him, I stood by myself knowing what they were doing was wrong.

In the introduction to The Power in Our Hands, Bill Bigelow and Norm Diamond write that to “teach is to be a warrior against cynicism and despair.” Our classrooms provide spaces for us to help students become warriors against cynicism and despair by acting for justice.