Rethinking Shit

Excrement and equity

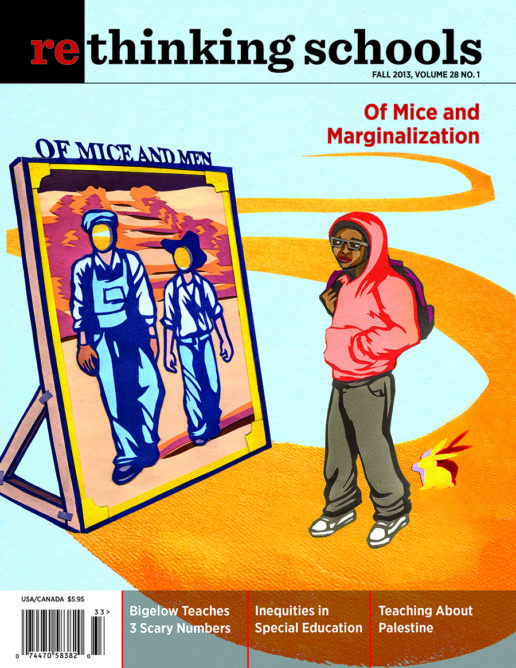

Illustrator: Erik Ruin

My students say “shit” multiple times a day. Rarely are they talking about feces. The word shit has been around for centuries. The Online Etymology Dictionary traces the word’s reference to excrement back to the 1580s, but its use for an “obnoxious person” goes back to at least 1508.

A couple of years ago, I started to change my approach to shit. While researching a unit on global water scarcity that I was teaching in my global leadership class, I came across a collection of essays, Written in Water: Messages of Hope for Earth’s Most Precious Resource, that features an article about sanitation by Rose George. George’s essay, “The Unmentionables,” is reprinted from her book The Big Necessity: The Unmentionable World of Human Waste and Why It Matters. George does a masterful job of illustrating why no one wants to talk about shit. It’s a gross and uncomfortable topic.

I have an excerpt from the introduction to The Big Necessity waiting for students on their desks when they walk into the classroom (pages 1-3). I ask them to read silently and to underline key facts and statistics. They discover that 2.6 billion people in the world do not have access to sanitation. That means no toilet, latrine, outhouse, or even a cardboard box. In other words, 40 percent of all humans on earth have nowhere to defecate. Women risk humiliation and rape when relieving themselves. And children grow up accustomed to the stench of human waste.

When my students have finished reading, before we discuss the content, I show a short video clip from the film Slumdog Millionaire. The scene begins just before minute 11, and shows the film’s protagonist, then a young boy, going to the bathroom in a hanging latrine in Mumbai, India. The boy’s friend locks the door from the outside just as a helicopter, carrying a famous movie star, is landing nearby. Not wanting to miss the chance for an autograph, the boy decides to take the plunge into a deep pool of shit. He emerges, covered in brown sludge, and successfully pushes himself through a crowd of shocked fans to meet his hero.

I show the clip to trigger an emotional reaction to the topic. The latrine scene is disgusting, and our natural reaction is often to laugh. It relaxes the students enough to be able to talk seriously about a seriously gross topic. When I stop the film, I ask the students to begin by giving me some facts about human waste that they learned in the George excerpt.

On the board, I record their comments:

“Diarrhea kills a child every 15 seconds.”

“90 percent of diarrhea is caused by fecal matter.”

“In one gram of feces there are 10 million bacteria and 10 million viruses.”

“The biggest medical invention in the last 200 years is sanitation.”

At this point in the lesson, I want to address the word shit and set some norms for how we will use it in our classroom. I ask my students if they know what code-switching is. There are several bilingual students in my class and they certainly understand when to speak English and when to switch to their home language. And most students understand that they speak differently around their grandmother or in front of a boss or a teacher than they do with their friends. But differentiating between the slang and literal meanings of a single word, especially one that is usually banned from school classrooms, is not as straightforward. I explain that we will soon be watching a video in which they will hear the word shit repeatedly. And I request that they commit to using the word only in the literal sense during the remainder of the class.

I ask students, in their table groups, to write down as many different words associated with feces as they can think of: poop, droppings, dung, defecation, stool, scat, and, of course, shit. Students usually giggle at first. I tell them: “When you use the word shit today, you must be speaking about feces. Try to avoid all slang uses of the word.” This requires a high level of self-awareness and can be a challenge for many students. My other motive for this exercise is to familiarize students with terms, such as open defecation, that they will hear frequently in the video.

The World’s Toilet Crisis

Now, with an agreement about how we will use language and some basic background knowledge of the connections among human waste, sanitation, fresh water scarcity, and health, we are ready to view the documentary The World’s Toilet Crisis, which is an episode of Current TV’s Vanguard series.

Vanguard was a brave documentary series that dared to cover issues that most television networks avoid: Islamophobia, the impact of the sushi industry on bluefin tuna, Brazil’s attempt to rid favelas of gang violence before the World Cup and Olympics, and many more. They were recently bought by Al Jazeera and, unfortunately, access to Vanguard’s work appears to be in flux (see Resources).

Vanguard correspondent Adam Yamaguchi opens the episode by saying, “Two weeks of shit conditioning have led me to a state where I can now hold a cup of warm, fresh shit and not throw up.” When I look around the classroom after this line, my students are glued to the screen with wide-open eyes. They are simply not accustomed to seeing this kind of material in school. Normally they might have laughed and started side conversations at this moment; because of our preparation, they handle it with maturity.

I show almost the entire 44-minute Vanguard episode during a 95-minute block period, with minimal interruptions. I want the students to absorb the images and have the space to react internally to what they see.

I do pause the video at approximately minute 7, after Yamaguchi reacts to a boat ride through a river in India that bubbles with methane gas due to the large amount of human waste in the water: “I would throw up into this river if I weren’t afraid of it splashing back up into my mouth.” Moments later, Yamaguchi does throw up while walking through a field where hundreds of people have defecated openly. I ask my students why they think the editors of the show left the scene of Yamaguchi vomiting in the final cut. One student comments: “It makes you feel like you are really there.” Another adds: “You feel grossed out and overwhelmed, too, when you see it.”

I pause the video again around minute 11. In this scene, Yamaguchi visits a New Delhi slum where there is a community effort to decrease open defecation. But there are only 10 toilet stalls for about 5,000 residents. Children still defecate into the only fresh water source. And families fetch their daily water for drinking and cooking from this source, which is essentially an open sewer. My students find this disturbing and ask why people don’t think about the consequences of defecating in or near a water source. It seems so obvious to them.

My instinct is to respond, “Where should they go?” Instead, I ask: “Why do you think people are living in these conditions?” I want students to remember that poverty does not simply mean that one cannot go out to eat or afford a cell phone. People living in extreme poverty around the world do not choose to have only a few gallons of water per day for all of their drinking, cooking, bathing, and other needs. Global economic inequality has endless consequences, including the difficulty, if not impossibility, of adequate sanitation.

About a half hour into the video, Yamaguchi is in Indonesia with a local sanitation activist. They are walking with a group of villagers and asking some of the men to show them exactly which piles of shit belong to them. They scoop up the feces and put it in a clear plastic cup, then walk back into town and show the cup to community members who are gathered in the street. People cover their faces and turn their heads away in reaction to the offensive smell of the feces. The sanitation activists use this reaction to begin a conversation about how easily feces can get into the water that they drink. This is an example of a community-led “total sanitation project” and it appears to be working. It is called total sanitation because it is all or nothing. If a single person defecates openly, everyone can get sick. As Yamaguchi explains, “Making people realize that they’re eating their own shit, and everyone else’s, by defecating in the same water they’re drinking from, is the first step in getting people to want toilets.”

This scene raises a danger of teaching this lesson. Watching people around the world learn that they should stop defecating openly can leave students with the perception that just educating about sanitation is going to solve the problem. It can easily reinforce conventional and paternalistic notions of how the world works and what it would take to make it a better place: “If only those poor people just knew how their bad habits are killing them.” “I certainly could never live the way they live.” “We should send teachers and nurses to poor countries to teach good hygiene.” Students need opportunities to think critically about problems like inadequate sanitation and to move beyond simplistic notions of why they exist.

I feel fortunate to teach a class that provides an ideal setting for exploring this complex topic. Our global leadership class was developed by Global Visionaries, a Seattle-based nonprofit organization that runs a youth leadership program emphasizing social and environmental justice. The class is designed to be a safe environment for students to critically examine the state of our world today. We consider building community an integral part of the class so that challenging conversations can occur more naturally, and we frequently discuss root causes of global poverty.

My students are fascinated by the video. They especially enjoy listening to Jack Sim, the president and founder of the World Toilet Organization. Sim, a native of Singapore, is a master of using humor to break down the taboo of talking about toilets. At one point, Sim and Yamaguchi squat on a shaky bridge spanning a river that also has served as a toilet. Sim says, “It’s quite nice. The wind is blowing. There is kind of a natural feeling.” He then transitions smoothly to the seriousness of the situation by adding, “But if I am a woman, someone will be looking at me.” Sim reminds us that not having access to sanitation is not just a threat to health, but also to human dignity and safety.

The Positive Side of Shit

In addition to illustrating many serious problems associated with open defecation, the video describes the positive side of shit. We see how human waste can be converted into organic fertilizer for agriculture. I ask the students how many of them like to eat bread. Most hands go up. What is usually the main ingredient in bread? Wheat, of course. Then I take out a small bag of compost made from recycled biosolids, and explain that wheat farmers love to use this product. In fact, according to a Washington State University study, wheat crop yields are significantly higher when using biosolids as fertilizer instead of ammonia-based, environmentally destructive commercial products. I walk around the room with a small mound of the compost in my hand and remind students that it comes from our shit. Some turn down my suggestion to take a sniff. Most try it and say that it just smells like dirt. I explain that after we flush the toilet, biosolids are pumped into large digester tanks at our local wastewater treatment facilities. After several weeks of “digestion,” the compost is ready to use. And during this process, some wastewater facilities are even able to capture and reuse methane gas for energy. (The King County, Washington, website has a wealth of information about its biosolids recycling process.)

This lesson sequence typically takes two 50-minute class periods or one block period. I prefer to teach it in a single long period so that students don’t lose any of their emotional response to the video. This year, I asked them to do a free-write response expressing their raw reactions to the lesson. Here are some excerpts:

This made me feel grateful for what we have; something so basic to us is hard for others. It also made me see that people can help solve this issue together. It will take time and work, but we can.

This film made me realize how much sanitation can affect many people around the world. This film shows that there is a problem and many victims don’t even know about it or don’t pay much attention. There needs to be more people who are brave enough to be leaders to try to make a difference.

I think those people who defecate [in the] open don’t want to do that; they have no choice [because] they don’t have toilets. The reason may be they are poor and the government is so slow to work on that.

This documentary was very interesting and disgusting! I hope that by the end of 2014 everyone will have a toilet to poop in and turn it into good fertilizer so we don’t need to use harmful chemicals in our crops. So they can be healthier and people can have clean water from rivers to drink and bathe and wash clothes. If everyone has a toilet, our water and land will be cleaner and that will also help with the water scarcity problem.

Reading through my students’ responses, I noticed that some are able to see past the simplistic “we can teach them” mentality and recognize that there are factors that people in extreme poverty have no control over. They are able to look at sanitation through a systems thinking lens. In other words, they understand that complex problems involve many interconnected variables and addressing only one part of the system is not sufficient. For instance, if a community builds a beautiful new health clinic, this may help doctors treat diseases, but unless people have access to clean water, adequate sanitation, and increased educational and economic opportunities, the health problems will persist.

Other students still need to think more critically about the root causes of the toilet crisis. I need to engage them in more study and discussions about why global poverty exists. They need more time to explore the relationship between sanitation and patterns of wealth and power around the world.

A Crisis That Entrepreneurism Alone Can’t Solve

The students’ oversimplification of the issue is due in part to the failure of The World’s Toilet Crisis to acknowledge the complexity of the problem. The video shows us how increasing access to toilets around the world creates new economic opportunities through the sale of new toilets and recycling biosolids. The emphasis is on entrepreneurial solutions, not on addressing the root causes of the problem. Although creating new jobs through new sustainable sanitation systems will certainly have a positive impact on communities, it is important not to ignore critical issues like the harmful effects of globalization and climate change that are keeping many of these same communities poor. We must help our students understand that, without seriously altering economic policies that benefit the wealthiest people on our planet, these problems will only get worse.

I ask my students what each one of them can do to contribute to solving the global problems that we witnessed in this lesson. I explain how I started taking action a couple of years ago by incorporating this lesson into my class. And how by writing this article, I hope to encourage more teachers to learn and teach about this important topic. A group of students decide to create a toilet newsletter with facts about the toilet crisis. The newsletters are posted in every toilet stall in our school (see Resources).

After the activities related to The World’s Toilet Crisis, we move on to lessons about personal water consumption, the bottled water industry, and global water scarcity. At the end of the unit, students take what they have learned and design a lesson for 4th graders at a nearby elementary school. Students often design activities like tap water taste tests and water carrying simulations. Students are taking action by teaching younger students, who will in turn bring their new knowledge home to their families, creating a ripple effect. Lessons on the toilet crisis require an added layer of sensitivity. My students have to think carefully about how to adapt the content in age-appropriate ways for the 4th graders.

Asking students to rethink shit has turned into my favorite lesson to teach each year. The word alone draws students in immediately. When students are willing to talk openly about such a taboo subject, the energy in my classroom is priceless. The lesson sends a message that I trust them to talk about an issue that most adults won’t even discuss because it is too uncomfortable.

Solving the world’s toilet crisis is complex, but not impossible. It’s going to take a lot of uncomfortable conversations to get there. Teaching our students how to talk about shit is one step in the right direction.

Resources

- “Biosolids Recycling,” King County, Washington. kingcounty.gov/environment/wastewater/Biosolids.aspx.

- George, Rose. The Big Necessity: The Unmentionable World of Human Waste and Why It Matters. Metropolitan Books, 2008.

- George, Rose, ed. “Shit: A Survival Guide,” Issue 82, Colors Magazine, fall 2011.

- Slumdog Millionaire. Directed by Danny Boyle. 20th Century Fox Home Entertainment, 2009.

- Steinberg, Ted. Down to Earth: Nature’s Role in American History. Oxford, 2002.

- “World’s Toilet Crisis.” Vanguard. June 10, 2010. Available on YouTube. We will update links on the online and digital versions of this article.

- “Toilet Stall Newsletter” written and distributed by Zeichner’s class.