Plea from a Haitian American Teacher

Illustrator: Donna De Cesare

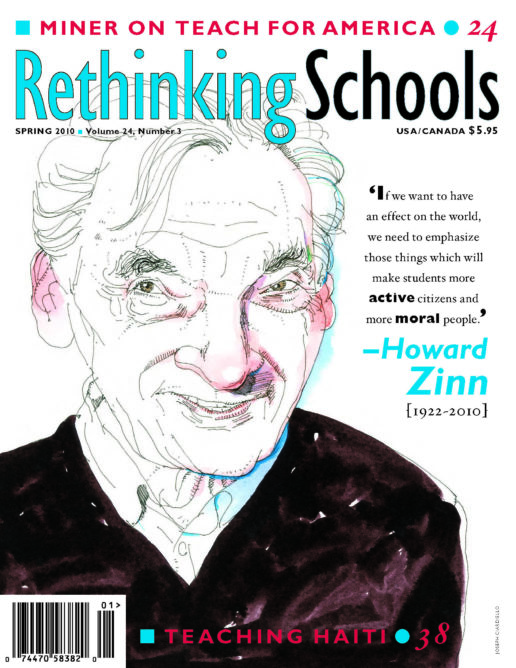

Marie Lily Cerat working with her 1st-grade class of Haitian

immigrants and African American children in Brooklyn, N.Y.

It took me four days before I heard from my folks in Haiti. The waiting was nightmarish. When I finally heard from my family—my aunt and cousins, my brother, his wife and children—I couldn’t stop crying. I was happy that they had made it alive, but saddened by the magnitude of the disaster that claimed so many lives. Having heard from my immediate family has not stopped the images of my people helpless, buried and dying under the rubble. Haitians and their descendants all over the world are grieving and mourning the terrible disaster and loss of lives that befell our homeland.

For a brief moment this winter, the whole world focused on Haiti. Educators at all levels—elementary, middle school, high school, and college—can take this opportunity to teach about Haiti: its past, present, and future. In the midst of this tragedy, I would like teachers to bring into classroom discussions the reasons why Haiti, once the richest colony in the Antilles, the most prosperous French colony, became so poor. This is important for students to learn. Haiti is never described without these ominous words: “the poorest in the Western hemisphere.”

It is my hope that teachers will explain to their students that, contrary to the belief that Haiti received any benefits for winning the war for independence against France, the country paid an indemnity to France in the amount of 150 million francs. After Haiti liberated itself from the grip of the French slavers, the rest of the world—including the United States, still a slave-holding country—refused to recognize and establish relations with Haiti.

They feared that befriending a nation created by former slaves would threaten their society and their economy, which relied on the unpaid labor of slaves: the exploitation, harsh physical and mental treatment of enslaved Africans and their descendants. The alienation and embargo placed on the new nation for nearly a century after its independence had a crippling effect that the country and its people still endure.

There is a lot to learn about Haiti and Haitians, and I hope that conscientious educators seize the moment to take Haitian history from its footnote status in our textbooks to more in-depth learning experiences in their classrooms. Few students in American schools are aware that a Haitian legion, 800 men strong, fought in the American revolutionary war for independence. In fact, a monument honoring the Haitian fighters was erected in Franklin Square in Savannah, Ga., in 2007. Many do not know that the founder of Chicago, Jean-Baptiste Point du Sable, was Haitian. Haiti and Haitians have long been contributing to American society.

Because of persecution, exile, and the dire economic situation, many Haitians have had to leave their homeland. During the dictatorship of the Duvalier era, we used to talk about the “brain drain”—Haitian intellectuals and professionals forced out by the dictatorship and the country’s unbearable conditions in search of a better life.

We have lost doctors, teachers, engineers, educators. So there’s a huge burden on Haitian academicians and professionals in the Haitian diaspora around the world to come to the aid of Haiti. Many left with dreams of returning and contributing in making Haiti a true “pearl of the Antilles.” Today, more than ever, we need to think of ways of actualizing that promise made to our Haiti.

I have always known that Haitians are some of the most resilient people. We are sure demonstrating that resiliency right now. Haitians are not only resilient, they are very creative and entrepreneurial; I am confidant we will rise from the devastation that has befallen our nation and people. We cry, we wail, but we never lose hope; we know our day will come.