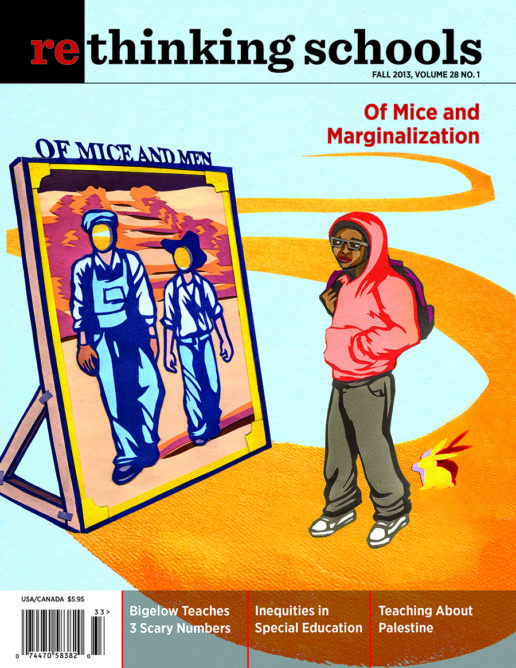

Of Mice and Marginalization

Illustrator: Bec Young

“What novels will you study?” It was Back to School Night at Madison High School in Portland, Oregon. My old job at Marshall High was over. After an emotional year of contentious debate, protests, and tears, the district had finally done it. They closed the building and the students were farmed out to other schools. I received a position at nearby Madison.

“And what exactly is A Long Way Gone?” Meredith’s mother peered at me over her copy of my syllabus. Like many of the parents at Madison’s Back to School Night, Meredith’s mother was white, middle class, and well educated. Back at Marshall, where many parents were bogged down by making ends meet and other obligations, we were lucky to see a handful of parents show up at Back to School Night. At Madison the room was packed. I wasn’t used to this kind of crowd.

“A Long Way Gone is a memoir of a boy’s experience as a child slave during the civil war in Sierra Leone,” I explained, trying to project an aura of professional self-confidence. It was difficult to maintain since my room was still in a state of chaos from the move. Every corner was stuffed with boxes. “It’s a part of my commitment to incorporate social justice themes throughout my curriculum. I’ve actually had a lot of success teaching this book as part of my unit on the International Rights of the Child.”

“It sounds a little violent to me.”

“It doesn’t sound like it would challenge my daughter at all. Will this prepare her for an AP class?”

“We read Lord of the Flies in 10th grade. Can you teach Lord of the Flies?”

“Well, to tell the truth, I don’t really like Lord of the Flies. It’s overly pessimistic about human nature, and all of the characters areД

“Lord of the Flies was the best book I ever read,” Meredith’s mother interrupted, looking at me steadily.

I tried to mentally gird my loins for a good fight to defend my curriculum. In Portland, high school English teachers have a great deal of choice in designing our own units. At my previous school, we enjoyed substantial autonomy, and many of us used it to collaborate on multicultural units around issues of race and social justice. Instead of teaching our diverse student body canonic books like Lord of the Flies or The Old Man and the Sea, stories written by white men about male relationships, I created challenging units on food and civil rights. After the earthquake in Haiti, I collaborated with colleagues on a unit around Haitian history. As a result, my students read books that weren’t necessarily on the usual core books list. They read Fast Food Nation and Alligator Bayou. They read Fences and Always Running and Mountains Beyond Mountains. They did not read Lord of the Flies.

All of this I should have explained to Meredith’s mother. But instead of fighting the good fight, I gave in to pressure and nerves, and I caved.

“On the other hand,” I continued, “if a lot of my students have already read A Long Way Gone, I could always substitute another reading. I could always teach . . .” My mind searched for an alternative that would please the crowd and not compromise my principles too much.

“Why not The Old Man and the Sea?” someone suggested. Heads nodded across the room.

“Actually, I was thinking about trying Of Mice and Men.” The words came out in a desperate squeak – I still have no clue where I got the idea, except for a dim memory of reading it in 10th grade myself. But it did the trick. The atmosphere in the room lightened immediately. Folks were smiling, the bell rang, and the crowd went home.

Back to the Canon

The next day, I reread John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men and fell in love. It was a beautiful read, one of those classic novels that bring a smile to people’s faces whenever they hear the title mentioned. No wonder the parents at Back to School Night had approved. I couldn’t put it down, and I couldn’t wait to teach it. So many things made this book perfect for a 10th-grade classroom. First of all, it was easy and short. There would be none of the groans I used to hear about longer, more difficult texts. Plus, it was engaging. The characters were vividly drawn, and the plot was simple but interesting. The themes of friendship, loneliness, and the cruel nature of the world were clear and readily accessible to adolescents. AlsoÐand to my reliefÐthe novel contained unmistakable social justice themes: the oppression of the poor and the weak in a capitalist economy; the way that racism and sexism weaken and erode the characters. Crooks, the African American stable hand, and Curley’s wife, a neglected and abused woman, are characters with spirits so beaten down that, instead of fighting back against their oppressors, they can only fight each other. It was perfect. In fact, you couldn’t order up a novel more suited to introduce literary terms, character development, foreshadowing, theme, setting, mood, the school of naturalism. And yes, I cried at the end, just like I did in high school.

I let myself be seduced by my new Steinbeck unit. I couldn’t have been happier, even though I had to keep it a secret from a couple of colleagues at other schools who never taught Of Mice and Men because “the only woman in that book is a dead woman.”

Many of my students thought it was the best book they had ever read. My classes worked on chapter questions and theme posters and literary essays. In a departure from my usual habit of writing all of my materials by myself (or using a trusted colleague’s curriculum), I blithely printed off worksheets from the plethora of materials available online and in my district. I told myself that I deserved the break. What my colleagues didn’t know wouldn’t hurt them.

I was teaching on the instructional equivalent of cruise control for the first time in 12 years, and it was fun. To tell the truth, back at Marshall, the social justice angle had occasionally been a hard sell: “Why are we studying Haiti? This isn’t a social studies class.” “Why do we always read so much about black people?” “Who cares about high fructose corn syrup?” “Why can’t you just give us worksheets like our English teacher last year?” For many of my students, reading Of Mice and Men was an expected 10th-grade rite of passage. Their parents and older siblings had read it, so no one was complaining.

“She Was Sort of a Slut”

But when we were three chapters into the novel, a lot of my Latina/o students – mostly girls – stopped coming to class. I coaxed many of them back, but could never persuade more than a few to read the book. “What’s the matter?” I would ask. “Is it hard?”

“No, it’s not hard,” Marisol told me. “I’m just not that into it, I guess.”

I also noticed that my African American students’ interest was dropping off. We had started the year reading and writing poetry and short stories that celebrated all of the students’ backgrounds and identities. My African American students enthusiastically participated in every activity; they produced and performed work that earned them the highest grades in the class. But as we got into Of Mice and Men, their interest flagged. “Is it the use of the n-word?” I asked Terrell, who hadn’t been to class in two weeks. Before reading the book, we had discussed the history of the n-word, watched footage of the NAACP’s symbolic funeral for the word in Detroit, debated its use in rap music, and agreed as a class that, although it was important to understand the historical context for the use of the n-word, we would not read it out loud or use it in class.

“No, I just don’t like Crooks. He’s a weird guy.”

“Is it the violence, the murder of Curley’s wife?” I asked Katie, who had been hiding a small graphic novel inside her copy of the novel during class reading time.

“No, I don’t like her anyway,” Katie replied.

“Don’t you feel a little sorry for her, though?” I asked. “Back in those days, women were so dependent on men for support. Her only power is in her sexuality, maybe her race. We talked about what the times were like back then.”

“I think we understand that it was a sexist time, Ms. Kenney,” Meredith interjected. “But she was sort of a slut.”

I reread the book over the weekend, and I had to agree with Katie. I didn’t like Curley’s wife much, either, even after Lennie kills her. Despite understanding her situation, despite knowing the sexism of the times, the tears that my students and I shed at the end of the book were not over the murder of the only female character, but over the demise of the male friendship Steinbeck so lovingly developed throughout the novel.

The more I thought about it, the more I realized that the problem with Of Mice and Men wasn’t limited to the fact that the only woman is a dead woman. The only woman in the book was one of the least sympathetic characters: a dim-witted, spiteful femme fatale who takes delight in using her looks to manipulate men, particularly vulnerable men like Lennie.

No one could argue that her murder isn’t wrong. Nevertheless, it is “sort of accidental,” as some students noted, and everyone’s sympathy ends up with Lennie and George, two buddies who have been together through thick and thin, only to be brought down in the end by a woman. No wonder some of the girls weren’t enthusiastic about Of Mice and Men.

The corrupting influence of women on men is a theme that creeps into many high school reading lists. There are many offenders, titles that I’d successfully minimized in my teaching, including Arthur Miller’s plays The Crucible and Death of a Salesman, and Ken Kesey’s novel One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. In Miller’s plays, women are rarely portrayed as anything but passive wives or destructive sluts. Kesey’s most well-known work similarly portrays women, like the infamous Nurse Ratched, as predators bent on destroying men’s spirits. In discussions, many of my colleagues downplayed the sexism, argued that the female roles are metaphors, or insisted that the other themes in these novels and plays have so much socially redeeming value they are still worth teaching. After all, Arthur Miller takes on McCarthyism in The Crucible, the myth of the American Dream in Death of a Salesman. These are classics of American literature, classroom staples, and indispensable texts for many high school English teachers. Who was I to even suggest that we stop teaching them?

When Students Check Out

I realized that I was also doing an injustice to my African American students. Although Steinbeck certainly acknowledges the racism of the times, his one African American character, the stable hand Crooks, is so embittered by racism, so disempowered, physically twisted and miserable that he is incapable of fighting back against the society that keeps him down. An adult reader might see Crooks as a symbol of the destructive effects of racism; most of my 10th-grade students, still struggling with the concept of metaphor, see a pathetic, embarrassing character with few redeeming qualities and no means to fight back.

But I didn’t understand this right away, and I finished more than one school day frustrated by the change in behavior I noticed. African American kids who previously led class discussions decided to check out. They stopped reading and complained that the novel was boring. Eyes glazed over with teenage ennui while thumbs got busy texting under desktops. A surge of extended trips to the bathroom left my two hall passes missing or in shreds. Heads were down on desks. Small groups loitered in the hall until an administrator brought them back to my room or sent them to the office. Even though I knew these kids and had seen the amazing work they could do, it was easy to interpret the texting and side conversations as defiance, and very hard to resist writing referrals and sending kids to the dean.

It wasn’t until the end of the unit that I asked myself if the African American students’ behavior wasn’t a clear signal that something was wrong with my teaching. I started to realize that the behaviors that I had interpreted as apathy or just downright naughtinessÐthe attendance issues, the lack of engagementÐwere a more conscious refusal to engage in a novel and curriculum that didn’t speak to them. If Crooks, the only African American character in the book, lacked the ability to fight back for himself, these kids were more than ready to act on his behalf by texting, napping, or hijacking my bathroom passes and voting with their feet.

Finally, the unit was over and I sat down to grade essays. The assignment was to explore a theme in the novel, a typical 10th-grade essay. Normally, I love reading student papers, but these nearly put me to sleep. My progress grading them slowed to a death march because I needed so many breaks between essays to work up the courage to return. The writing was skimpy and dry, as if my students had treated this as just another academic hoop to jump through. Plus, I realized that five essays out of 75 contained whole sections lifted from the internet, something that had rarely happened to me before.

After a little detective work and a few tough conversations, I came to the conclusion that plagiarism is just what happens when you open a can of curriculum and assign 60 15-year-olds a generic essay subject. What did I expect? The internet is not only a great place for teachers to mooch free lesson plans; it’s also a great place for students to find trite essays on Of Mice and Men, The Crucible, or any other reading in the high school canon. It was too tempting to copy and paste. Before the essays came in, I felt guilty about marginalizing the girls and African American students, but the uninspired writing I got about Of Mice and Men convinced me that this unit had done a disservice to all of my students. I learned my lesson and decided to move on.

A Raisin in the Sun

Our next reading was A Raisin in the Sun, Lorraine Hansberry’s famous play about an African American family struggling against racism and poverty in the 1940s. I chose it partially because it is a play often read in high school, one I knew parents would accept. I also chose it because Hansberry, an African American woman, shapes her characters and their conflicts in a way that I believed my students could relate to. In A Raisin in the Sun, the characters confront many of the same obstacles as Crooks and Curley’s wife, but they are drawn as complex people and they respond very differently to their circumstances. For example, Beneatha, the daughter in the family, is a strong, bright, optimistic girl determined to become a doctor, despite the odds against her as an African American and a woman. Instead of succumbing to the racism and sexism prevalent in her day, Beneatha fights back.

Right away, I noticed that this agency on the part of the character opened up possibilities for my curriculum. Not only were we discussing racism, we were discussing resistance. As the characters developed, there were more questions to ask and answer, more discussions to have, more writing to do, more connections to make to my students’ lives, and to the history and demographics of our own city, Portland, once notorious for keeping African Americans in certain neighborhoods and out of others.

The students who had tuned out the Steinbeck novel perked up. Everyone was eager to listen to the play and read it out loud. This time, instead of assigning essay topics, I had the students keep dialogue journals following a theme or character of interest. I let them choose their own topics to write about based on their notes and commentary.

The essays I received at the end of the unit were a far cry from the previous batch. This time students of all races and ethnicities were performing to a higher standard than before, instead of jumping through hoops to get a grade. They wrote about Raisin in the Sun with the passion, depth, and the intensity that was missing from the previous essays. They wrote about Beneatha’s struggle to overcome the stereotypes holding her back, about Walter’s dream of going into business, about Mama’s steadfast love and support for her family and their dreams. They saw that, although these characters were facing many of the same roadblocks as Curley’s wife and Crooks, they were fighting back with the courage and dignity Steinbeck’s two-dimensional characters lacked. My students understood the weaknesses of this all-too-human family – Walter’s gullibility, Beneath’s temper – but admired their struggles and found many parallels between the characters’ experiences and their own.

At the beginning of the next school year, I confronted the dilemma I had been avoiding for nine months: Do I teach books that a narrow but vocal segment of the community promotes, or do I return to teaching equally challenging novels, plays, poems, and nonfiction works that speak to all students in terms of the themes and characters they introduce? I began the year prepared to have conversations about the suitability of the literature some parents expect to see on my syllabus. I decided to trust myself, my education, and my own experiences when making critical decisions about what will work for everyone in our increasingly diverse school, not just those whose parents are able to show up for Back to School Night.