Documenting the Undocumented

When immigrant students count — and when they don't

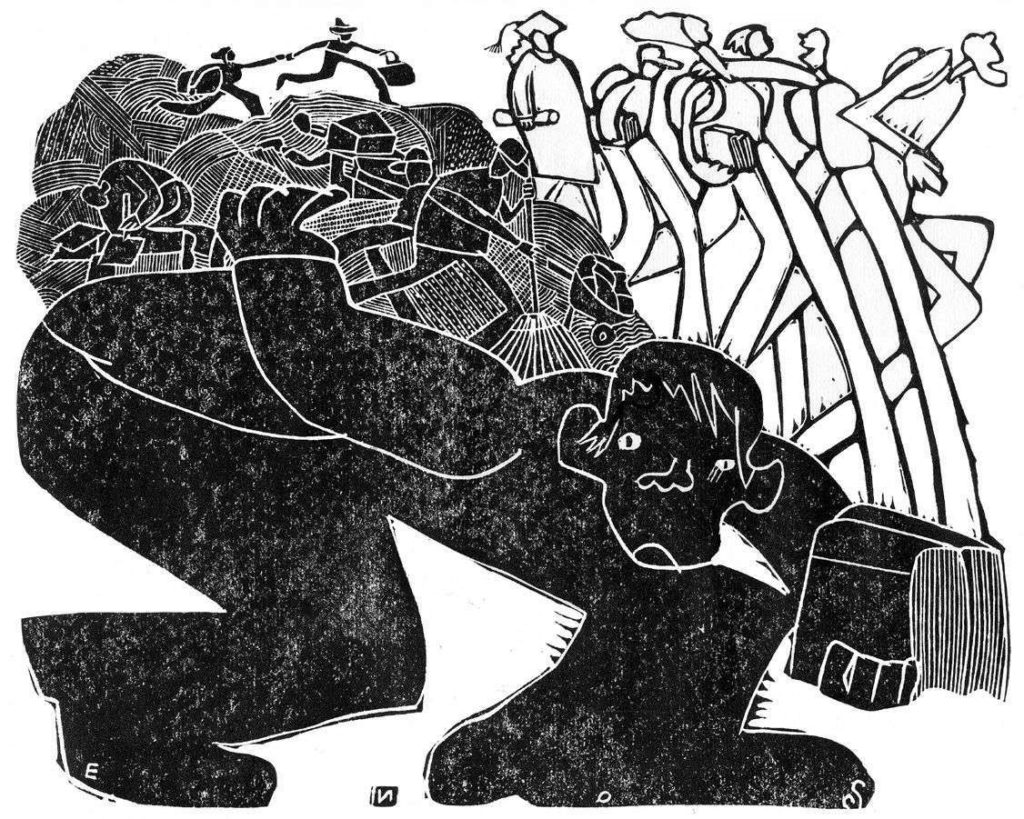

Illustrator: Randal Enos

The principal stood in front of the faculty, framed by her chart packs filled with current statistics. It was the speech all teachers have endured. Here’s the familiar scenario. We look at the aggregated results of students’ performance on standardized tests. We recognize the categories: Exceeds expectations, Meets expectations, Does not meet expectations. Then we examine the disaggregated data of the sub-groups.

Sadly, my school, an urban high school on the west coast, followed national trends. Certain subgroups — African American, Hispanic, English Language Learners (ELL), and Special Education Students (SPED) — did not meet expectations that year. As a result of our “failing” subgroups, my school continued its status as a member of NCLB’s ignominious list of schools not making adequate yearly progress. We were heading down NCLB’s stairway from needing improvement to the dark basement of reconstitution or state takeover. This dishonorable descent creates clouds of doubt, even panic, in any teacher’s heart. We know and love our students; we see their enormous potential; they delight us daily with their comments and antics. We attend workshops, confer with colleagues, spend endless hours in meetings, and submit to advice from outside consultants — all in the name of our students’ growth and progress. Yet, the numbers are cold, ugly reminders that the government finds our efforts and our students’ performance lacking.

As an English as a Second Language (ESL) teacher, I am most connected with the Hispanic, Asian, African, and Eastern European students comprising a vigorous ELL population. As I looked at the data, I felt increasingly agitated by the act of turning the faces of my students — Lidio, Carla, Hoang, Sheyla, Ibrahim — into statistics.

But, even worse, I was angered by the disingenuous governmental stance toward my Latino students, over half of whom are undocumented. These students, without green cards or Social Security numbers, are expected to be invisible; they are the casualties of a national double standard. For the purpose of NCLB’s adequate yearly progress, my students “count;” and, if they don’t perform up to standards, headlines point accusingly at schools. Yet, in the broader society, my students are unambiguously left behind. The official message is: keep test scores up, keep the dropout rate down, and maintain high attendance rates. The unofficial message is: undocumented students don’t matter. They’re ineligible for college scholarships, they have no health care, their parents work long hours at minimum wage jobs, deportation is always a possibility, poverty is a reality. The hypocrisy outrages me.

As educators, we look at students as real people with stories, strengths, personalities, vulnerabilities, and talents. We learn to love them, care about them, struggle with them, encourage them, stay connected and hope for them. For us, they count. Whether or not they’re documented isn’t relevant to our feelings. Our job is to push them to their potential.

I remember one of my former students, Mario. He was undocumented; his family was from Mexico, and his parents had never attended school. Poverty forced his parents to make the difficult decision to journey north. Like his parents, Mario had experience doing nursery work, but he wanted other choices — possibly a career as a P.E. teacher or in business. His determination drove him like a freight train. He worked hard and long at the complexities of writing an essay; he relished the autobiography Breaking Through by Francisco Jiménez, the story of a boy from a migrant family who overcame obstacles to become a college professor and author. Mario committed the same energy to soccer and track; he was a star, in spite of having to wear donated track shoes. His desire to go to college was palpable, and all his teachers encouraged him. During his senior year, he filled out the Free Application for Federal Student Aid — the FAFSA — writing zeros in the boxes for the Social Security numbers. He applied for numerous scholarships and, in fact, received a $20,000-a-year corporate grant. He was so close, yet so far. He could not accept the grant because he had no Social Security number. Ultimately, he received one scholarship of $5,000, secretly underwritten by a staff member at the school. Thinking about Mario, I sometimes feel I lied to him by encouraging him.

Mario is not alone, although many undocumented Latinos give up before he did. There is no carrot to staying in school and graduating. Then what? And even if undocumented students do somehow make it through college, what kind of profession can they enter without a Social Security number? Often, the lure of working and actually making money, albeit at a minimum wage job with counterfeit identification, surpasses the desire to finish school.

Instead of adhering to contradictory policies of “now you count; now you don’t,” it would make better sense to reward students’ hard work. Why not provide more options by ratifying the Dream Act, whereby undocumented youth are offered legal status, so that they can pursue college and later become working professionals? Instead, the Dream Act lies dormant in some congressional committee.

Latino students’ futures are precarious in other ways. They know deportation might be just around the corner. In June 2007, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents staged a massive raid at a local fruit-packing factory. The majority of the employees were undocumented women. Two of my students, Sonia and Manuel, had their lives turned upside down when their mother and older sister were arrested in the raid. ICE sent the sister to a holding center in Tacoma and later deported her. They allowed the mother to return home wearing an electronic bracelet to track her whereabouts. She and Manuel were later deported, while Sonia was allowed to remain because she is married to a young man with documentation. The raid happened in early June; Sonia, a hard-working, responsible young woman, was too traumatized to take her final exams. The following year, she was back in school in spite of her grief about the dissolution of her once tight-knit family. A few months later, Sonia seemed particularly distraught and unable to concentrate on schoolwork. I asked her what was going on. She reported that she hadn’t been able to sleep for the past two nights because her mother and 15-year-old brother were trying to come back across the border with a group. Her mother suffers from diabetes, which impeded her walking. Consequently, the group abandoned her brother and mother, who had to return to a Mexican border town to await another opportunity to cross. The ending was a happy one for the family because Sonia’s mother and Manuel managed to get to Phoenix and finally home. I continue to marvel at these students’ strength and tenacity in the face of such tumult and stress. It is remarkable that Sonia and Manuel remain in school despite the forces against them. The ultimate absurdity is that, shortly after Manuel arrived, he was required to take the 10th-grade state writing test.

My students’ need to help their families survive often supercedes their desire to do well in school. My undocumented students’ parents sometimes work two minimum wage jobs, and their teenage children frequently pitch in, working after school, often until 10 or 11 pm. Occasionally, the pressures of working to help support the family and going to school at the same time are overwhelming, and the students reluctantly drop out.

I remember Ismael, a bright, affable young man, who was the sole supporter of his mother and sisters back in Yucatan, Mexico. He eventually quit school because his full-time job conflicted with his school schedule, but he left with hopes of continuing his education at a local community college.

In other cases, students stay in school against enormous odds. Carolina was an academically talented 12th grader from Mexico, who worked evenings and weekends as a waitress to help support her family. At one point, her parents were out of work and confided in a bilingual assistant that they had only tortillas and salt to eat. Carolina was paying the rent and the bills. She had no time for homework but still managed to pass all her classes and graduate. I encouraged her to attend the local community college, but she was skeptical about the possibility and opted to work at a cannery instead.

Another student, Rogelio, was homeless. His father had been injured on the job and was unable to work. The family was forced to live with relatives and friends; Rogelio never was sure if he would be at school the next day or not. There was no safety net for this family, no welfare, no food stamps. In another situation, Alberto, a 10th grader, had to drop out of school temporarily to take care of his young sister while his father was incarcerated for outstanding traffic violations. The stories of family stress and resiliency don’t stop. These struggles count — in students’ academic performance, in their future education possibilities, and of course, in their test scores.

Crossing the border illegally is traumatic. Even though it’s parents who make the decision to enter the United States, it’s children who lose their innocence. They leave the safety net of family and friends and venture into an unknown, dangerous world of a hostile desert crossing, fearful encounters with the Border Patrol, and a lingering nervousness about being caught.

In some cases, the parents make the journey to the U.S. first, save up money for the coyote and send for their children later. One of my students traveled from Honduras through Mexico, where the police intercepted him and his brother. Both ended up in a Mexican jail for a few months and much later reunited with their parents in the United States. Two other students, sisters, came after the parents had found work. The girls had to lock themselves in the bathroom of the supposed safe house because they were afraid of being molested by their guides.

Stories like these set these children apart. They know they are not in the mainstream. They know they’re considered illegal and therefore unacceptable in many people’s eyes. They feel different from American kids and somewhat tainted. In my high school, they rarely become full participants in the social, extracurricular, and academic scene. Too many become dispirited and disengaged and we lose them. Others cannot escape their anger; they find their social network and sense of belonging in gangs. It is remarkable, however, how many Latino immigrant students do stick it out and remain in school. They value education in spite of the difficulties of illegal status and the government’s doublespeak. How much better it would be for all of us if my students really did have the same rights and opportunities as others, if the same standards really did apply to all. How much better it would be if these students could actualize their potential rather than exist simply as statistics in a duplicitous national educational policy. How much better it would be if equity were a reality, and not just political jargon.