Children With Absent Parents

Recently, while browsing Facebook and procrastinating, I came across a disdainful post shared by a friend. It was a bashing of a picture book about a kid’s father going to jail. Bunny rabbits were the main characters. People went wild. “Why are the bunny rabbits brown?” one person demanded. “Having kids tell family business,” another griped. “Can our kids just have normal picture books without being reminded that their dad is gone?” another person asked. My reply: “Why not let them know they’re not alone in this world?”

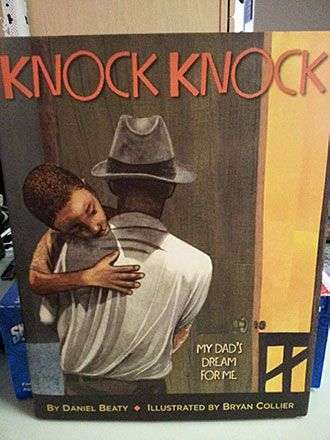

The first poem I ever had my middle school students listen to was a live performance of “Knock Knock,” by Daniel Beaty. By the end of the poem, they were speechless. But, boy, did they have lots of words and tears to share on paper! It turned out that each and every child had a common thread with Beaty—needing love, guidance, and presence from a parent. Many of them shared another thread with Beaty: They were searching for the courage to find themselves and grow despite parental absence. “Have you ever shared this with anyone?” I asked them. “No, we can’t,” they replied. “Family business.”

Knowing the power of the spoken word version of “Knock, Knock,” I was excited to read and share Knock, Knock: My Dad’s Dream for Me. Beaty begins the book as he begins the poem: A young African American boy plays a special game that starts with his father knocking on his door every morning. One morning, his dad doesn’t knock. The boy waits and waits, but his father doesn’t come back. The boy writes a letter to his dad, expressing the pain he feels, knowing that he will be deprived of the things fathers traditionally teach sons:

Papa, come home, ’cause I miss you,

miss you waking me in the mornings and telling me you love me.

Papa, come home, ’cause there are things I don’t know,

and when I get older I thought you could teach me

how to dribble a ball, how to shave. . . .Papa, come home, ’cause I want to be just like you,

but I’m forgetting who you are.

Beaty juxtaposes this pain with the power of the father’s love. The dad writes back, and his advice propels the climax and resolution of the book, listing all the things his son will have to learn to “knock” for himself, knowing he has his father’s love behind him:

No longer will I be there to knock on your door,

so you must learn to knock for yourself.

KNOCK KNOCK down the doors that I could not. . . .KNOCK KNOCK with the knowledge that you are my son and you have a bright, beautiful future.

For despite my absence you are still here.

Though the poem is rooted in Beaty’s experience as a black man, the illustrations speak to all children. Bryan Collier does an incredible job, using paper, prints, drawings, and textiles to create lifelike, multidimensional images. As the child realizes his father is gone, the images become progressively more imaginative. At one point, he rides a paper airplane in the sky. The most captivating, storytelling image in the book, however, is one in which the faces of many different children—black, white, Latina/o, Asian, boy, girl—are superimposed atop closely built apartment buildings. The young, wide-eyed boy seems to speak for them all, arms outstretched, his face and arms all questions, and Dad’s old fedora flying off of his head.

Growing up as a black child, I was taught not to tell “family business.” Though I was blessed enough to have an amazing mother and did not experience abuse or neglect, I’ve had my share of hungry days, wayward siblings, and fatherless nights, weeks, months, years. I couldn’t go to school and talk or write about my sadness without teachers jumping to conclusions. I couldn’t go to church and sing about my sadness without the saints gossiping. So I, like many other black children, kept a lot inside. It wasn’t until I began teaching poetry that my perspective changed.

I understand the urge to withhold some family details. Traditionally, that urge is based in very real fears. The United States has been kid-snatch happy. We have a history, particularly affecting communities of color, of deeming homes unfit for children simply because they don’t meet a cookie-cutter standard of living. Add to that a diagnosis of depression or an old shoplifting charge, and it is a recipe for child protective services involvement, even if the parent is doing a fine job at parenting.

The problem is that we make kids hold in issues that most adults can’t even cope with. Our children need to know that they are not alone in grieving the loss of a parent who is absent for whatever reason, including death, divorce, or incarceration.

They also need to know that confronting life’s pain yields power. This is what Daniel Beaty and Bryan Collier successfully express in this extraordinary children’s book.