Celebrating Skin Tone

The science and poetry of skin color

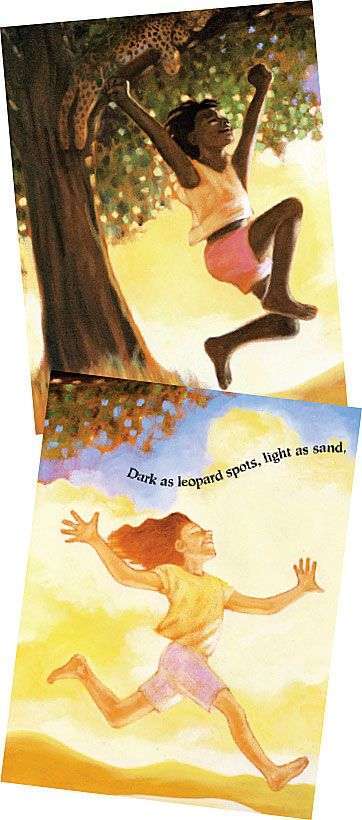

Illustrator: Sheila Hamanaka

When I look out at my room full of 1st- and 2nd-grade students, I see a symphony of colors. I see this as beautiful and invaluable. Yet I realize the world does not always embrace my students’ multiracial reality. I know that the world will not receive Jamal with his skin the color of summer midnight and his easy laugh the same way it will receive Anita, with her skin the color of late summer wheat and her quiet smile. Young people, like adults, receive countless confusing and negative messages about the implications of skin color. Consistently they get the message that some are better than others—that white trumps black and brown.

Worse than an unwelcoming world is the possibility of an unwelcoming classroom and school. I see racism taking root in the relationships my young learners are establishing. I have had to step in and help my students negotiate their multiracial environment—whether it is stopping a white student from assuming an African American classmate is the one who needs to go with the parent volunteer to work on reading skills, or helping a student of color find a group to join when, once again, she has not been invited into the dramatic play of a group of white girls. Knowing this, I am always on the lookout for learning opportunities that will be accessible and affirming.

When I attended a workshop led by Katie Kissinger demonstrating her approach to celebrating skin tone with her preschool students, I knew I had found a new possibility for beginning to disrupt the skin color prejudice that harms my students on a daily basis. Kissinger’s students had celebrated their skin tones and learned about the biological basis of skin color. Young children, like adults, see different skin colors—and assign meaning to these differences. I wanted my students to understand something of the science of skin color in order to challenge the notion that skin color is an indication of anything more than genetic adaptations to one’s environment. My aim with this lesson was twofold: First, I wanted students to see their similarities across a skin tone spectrum. This would be the science of skin tone. Second, I wanted them to practice the art of praising their own skin tones as a way to access the connection between skin tone and identity in a positive way. This would be the poetry.

The Science of Skin Tone

I began the lesson by grounding my students in the science of skin tone. Kissinger’s own book, All the Colors We Are, offers clear explanations for why people have different skin tones. My students were fascinated by the idea presented in Kissinger’s book that all people come in shades of brown. Exclamations like “Yes, why do they call me white? I’m not white. I’m pinkish brownish tannish goldish” peppered the cluster of students gathered on the rug for read-aloud. Kissinger’s book presents different skin tones as adaptations to different environments. Imagining the evolution of skin tone over millennia is beyond the scope of most 6- and 7-year-old imaginations, but the idea that our skin has tone to make us a good match for our environment, that our skin tone could be understood as a way to make us stronger, offered my multiracial class a path into this conversation. I also used the book Your Skin and Mine by Paul Showers to introduce key ideas and scientific concepts. Reading each book aloud, I asked students to turn and talk after most pages so they could monitor their own growing understanding. We created a word wall dedicated to words related to skin tone. Melanin, tone, genetic, and heritage all took places of prominence on the wall.

Using the books and students’ understanding, we wrote a kid-friendly definition of each term. We defined melanin as the stuff in your body that gives your skin and hair its color. Students came to understand genetics as the recipe for how one’s body will be built. After reading these books, my students stood on solid ground with some basic ideas: Skin tone has evolved over time; it is an adaptation to different environments, especially proximity to the equator; and everyone, regardless of how one’s “race” is named or misnamed, is a shade of brown.

Once students had some understanding of the science of skin tones, I moved into the language of praise. Following Kissinger’s lead again, I stopped by the local hardware store to collect paint chips in dozens of shades of brown and peach and tan. I wanted my 6-, 7-, and 8-year-olds to match paint chips to skin tones, just as Kissinger had done with her preschoolers. I gathered the class on the rug so everyone could see me and the paint chips. Holding out the top of my forearm, I laid a paint chip against my skin. “What do you think? Does this look like my skin?” I asked. Thinking aloud, I modeled deciding which chips seemed too dark or too light, which ones had too much blue or too little red. Soon I asked my students to help me in my matching process, finally landing on a good match. I read the name of the color, Caramel Whip, to the group and wrote my name on the back of the paint chip.

Then I released students to explore the chips I had spread around the room. They mingled and chatted, helping each other find a good match for their own skin. To close the day’s lesson, all the students shared their chips with the class, to applause after each share. Jessica, who had been frustrated by not finding a perfect match, landed on Saddle Brown with help from a few friends. Fergus went with Beach House, Justin and Tyler both identified with Coconut Grove, and Samantha’s color match was called Liberty—a great match for her. I collected their paint chips to use when we transitioned to writing poems.

The Poetry of Skin Tone

I began the writing process by reading Sheila Hamanaka’s picture book poem All the Colors of the Earth. First, I simply read the poem aloud slowly, taking time so we could look closely at each illustration. I had students pair-share their favorite pages, and a few shared favorites with the whole class. Jamal was especially fond of the line “the roaring browns of bears and soaring eagles.” As soon as he shared that as his favorite line, six or seven hands went down. Apparently this had been a favorite. Raina offered up the line “like caramel and chocolate and the honey of bees.”

“Why do you like that one so much?” I asked.

“Those are all sweet,” Raina answered. “I think the poem is supposed to make us feel happy and those things make me happy.”

Students continued to share new favorites or restate ones that had already been shared for a few more minutes. It was important to me that students have a chance to simply connect with the language and imagery Hamanaka uses. Often the message students receive, especially white students, is that to talk explicitly about difference is to be racist. We needed our exploration of skin color to begin with a gentle, welcoming discussion.

After students connected with the poem, I moved into the craft of writing. I wanted students to begin to think like poets. I tailored my questions toward the moves Hamanaka used, hoping students might be able to replicate those moves. “Sheila Hamanaka uses a lot of comparisons in her poem,” I began. “Who remembers one thing she compared skin tone to?” Students called out bears and eagles and seashells and chocolate. I tried to keep up with the flurry of ideas as I recorded their connections on chart paper.

“Sheila Hamanaka chose her comparisons very carefully,” I told my class. “How do you think she feels about skin tone based on the comparisons she chose?” I pushed students to recognize that the poem is a praise poem in celebration of skin tone. I reminded students of Raina’s idea that the poem makes her happy because Hamanaka compares skin tone to sweet things. Ted thought Hamanaka believes that skin tone makes you strong since she used eagles and bears in her poem. Larry said that the poem made him feel peaceful because it compares skin tone to whispering grass and the ocean.

“How do you feel about your skin tone?” I asked, a little apprehensively. Even though I had laid the path for praise of skin tone, there was still the possibility that some students would have negative concepts of their skin tone and others would claim to have no feelings at all. To maintain a praise focus and offer some additional language support, I suggested that students choose one of the feeling words we had just listed if they did not want to think of their own feeling word. “Happy” and “strong” were the most popular feelings, and that was good enough for us to move forward with the poets’ work of comparing.

“What is one thing in the world you can compare your skin to?” We closed that day’s lesson with students mingling around the room and sharing their comparisons with as many partners as they could. I listened closely to the partner shares, especially eavesdropping on my students of color. I do not want any of my students to feel under a spotlight or that they need to be representatives of their group. What I realized in my eavesdropping was that my students of color were better able to generate lists of comparisons with their partners than some of my white students. I suspect that white students are less practiced at paying attention to their own skin tone. I used suggestive questions and references to nudge some students toward richer language and also toward celebration.

Jeremy, a first-generation child from Eritrea, suggested his skin was the color of dirt. Jeremy’s comparison stirred concern in me. Of all my students of color, he was the most socially isolated in the class. I only knew of one other student who has ever played with Jeremy outside of the structured school day. Other students often complained about having to partner with him or tattled about his behavior in P.E. or in the lunch line. Sitting next to him and seeing his paper with dirt as the lone idea listed, I wondered what his motivation was for that comparison, and I wondered why he seemed at a loss for other ideas.

Rather than admonish him for a potentially negative comparison, I probed his connection: “What type of dirt do you imagine? Is it like fresh soil ready to be planted in a garden or like the rich muddy edges of a pond or like the dry patch in front of the soccer goal?” As an expert soccer player, Jeremy ended up with several references to the types of dirt on the field. I cannot be certain Jeremy’s original idea of dirt carried negative connotations for him, but I can attest that his face brightened as he added more ideas to his brainstorming chart and his hand went up to share as we closed the lesson. Fergus, a white student, said he couldn’t think of anything other than the color of his paint chip. I sent him over to the area of our classroom library with large full-color science books. “Flip through some nature books and see what you find that reminds you of your skin tone and how you feel about it,” I suggested. He came back to his seat 10 minutes later with river stones and prairies for his list. Since Fergus spends every summer fishing with his grandfather in Montana, these seemed like excellent choices.

The next day, I introduced another set of poems in praise of skin tone from the book The Blacker the Berry, by Joyce Carol Thomas. Each of these poems describes one of the many hues of African American skin color, from deep rich browns to red to seemingly white. Thomas uses images from nature and dialogue between children and elders to celebrate skin tone. For example: “I am midnight and berries/I call the silver stars at dusk/By moonrise they appear/and we turn berries into nectar/Because I am dark the moon and stars/shine brighter/because berries are dark the juice is sweeter.” Thomas links feelings about skin tone to family, referring to grandparents’ advice, motherly love, and heritage: “My mother says I am/Red raspberries stirred into blackberries/Like the raspberries I will always be here/Like the blackberries I was here with the first seed.”

For each of these poems, I asked students: “How does Joyce Carol Thomas describe skin tone?” Students added to the chart that we had started with Hamanaka’s poem. Thomas’ work gave us additional categories: family memories, berries, sky colors, and feelings. Now we had enough poetic moves and categories borrowed from other poets to move into generating student ideas.

I designed a brainstorming template for students to use based on what they had noticed in Hamanaka’s and Thomas’ poems. Our big categories included: nature, animals, smells, food, and emotions. We gathered on the rug and I showed students a chart paper-sized version of the brainstorming template. “These are some of the ways we noticed other poets described skin tone. Today, we are going to think of our own ideas about how to describe our skin tones.”

Then I modeled the process of thinking about how to celebrate and describe skin aloud. I pulled my paint chip from the basket of chips and re-read the name of the color: Caramel Whip. “Where would I put this on my chart?” I asked the class. We agreed it belonged under foods. “Let’s see if we can think of any other comparisons for my skin.” I looked closely at the back of my forearm and showed it to the students sitting closest to me. “What in nature is like this color?” I wondered aloud. “It looks a little like beach sand,” I began and added this idea to the chart in the category Things in Nature. When I asked students for more nature comparisons for my skin color, they called out “bunny fur,” “dry grass,” and “peaches.” All of these went onto the chart.

I wanted students to start thinking about their own skin. “What did you tell your partner yesterday that you compared your skin to?” I told them to share again with a nearby partner. “Who can share their idea?” I asked after a few minutes of partner talk. Many hands went up.

“Cocoa,” said Sayla.

“Lovely,” I responded. “Where would that idea go on the brainstorming chart?” Working with the students, I modeled placing their ideas onto the chart under the appropriate category. The categories themselves were not that important. My goal was to generate a variety of ideas.

When I felt confident that students had a sense of how to sort their ideas, I released them to work on their own brainstorming charts. “Try to get at least one idea in each section,” I recommended as students settled into desks and corners of the carpet to fill out charts.

While students chatted and listed ideas on their brainstorm charts, I again roved and made sure each student came up with ideas celebrating their color. Not every student immediately settled down and brainstormed 10 or 12 poetic images in praise of their skin tone. Many needed one-on-one help to get rolling or to keep going. Neil struggled to come up with ideas, so I paired him with a trusted friend to think together. Katie listed white paper and milk as her skin tone and said she was done. We studied her skin, laying her arm next to mine to see that the pinked-up creaminess of her skin tone had little to do with the name of her race as white. She added strawberries to her milk to get closer to the real tone of her skin and came up with one of my favorite ideas—grilled cheese bread. Jason stared into space from his seat, so I pulled up a chair next to him and reminded him to start with the name of his paint chip. We studied his forearm together and imagined lions with their golden hair shining in the sun and cookie dough. Josie’s pencil couldn’t move fast enough to list all the browns in the world that her skin reminded her of, so I asked her to share her thinking process with the class. Some students ended up with only two or three ideas, but that was enough to get rolling with the poetry.

Poets as Advisors

Now students were ready to sculpt their ideas into poems. I once again relied on think aloud as a modeling technique. I gathered the students on the rug and reviewed the oversized brainstorm chart we had made as a class the day before. “I am going to take these ideas and turn them into a poem today. You are going to take your ideas and turn them into a poem as well. I need some advice on how to do this. First, I am going to take advice from Sheila Hamanaka and Joyce Carol Thomas.” I had a couple of student volunteers read aloud once more the skin tone poems we already knew.

“I think I am going to start my poem with an idea from Sheila Hamanaka,” I said as I began writing my poem on chart paper. “I am not going to copy her whole poem, but I want to use one of her ideas as a way to jump into my own poem.” I wrote: “I am the colors of the Earth” at the top of the chart paper. Next, I looked back at the chart of brainstormed ideas and dramatically modeled choosing an idea to add to my poem. “I think I will use this one next,” I said pointing to dry beach sand. I wrote: “My skin is the color of warm beach sand.” “What idea should I write next?” I asked the class. Working together, we drafted four or five lines for my poem.

It was time for students to write their own poems. As a way to remind them of the options we noticed in the model poems, I released them from the rug by asking who wanted to start with which type of idea. “Who thinks they will start with a food comparison?” I asked. “Who wants to include a detail about how your skin is like the skin of someone else in your family? Who wants to start with hair instead of skin? Who wants to start by comparing it to an animal? Tell a neighbor how you will start your poem.”

We wrote for the rest of the week. Some days we cranked out longer sessions of 45 minutes of writing and sharing. Once or twice, we simply squeezed in 20 minutes before lunch. But each day that week, students touched this work—writing, rereading, sharing with friends, sharing in small groups, and sharing all together. For students who were ready to stretch as writers, I led a revision lesson on adding more detail to their metaphors. I modeled adding action to the image of an eagle so it became an eagle soaring through the mountains. If students compared their skin to caramel, that caramel could become warm caramel or caramel inside a candy. First- and 2nd-grade metaphors tend toward the cliché, but I wanted them to try to stretch their ideas.

When students seemed satisfied with their poems, we created self-portraits. I let students choose the medium—paints or crayons—that matched how they wanted their portraits to look. Poems and portraits hung in the hallway for several months, the students protesting whenever I wondered if it might be time to take them down.

I know that children see and wonder about skin color. I know that children, even as young as 6, experience racism directed at themselves, their moms, their neighbors, their cousins, the man in front of them in line at the grocery store. I also know that opening my classroom to a discussion about the skin tone differences that we see and the ones that we ignore is one component to disrupting prejudice based on skin color. And I know that this is just the beginning—sharing an experience around loving our skin tones does not suddenly take away the real pain of how the world sees “white” and “black” and “brown” skinned peoples.

The two weeks we spent writing and learning about skin tone opened my classroom in some important ways. Samantha, an African American girl who barely spoke even in morning circle time at the start of the year, read her entire poem aloud to her classmates. Tyler and Justin, one white and one African American, who had never spent free time together before, became friends when they realized they both had skin that matched Coconut Grove. Jeremy, also African American, finished a piece of writing on the same schedule as the rest of the class for the first time.

Maybe Samantha was simply ready to emerge as a more vocal and public presence in the classroom. Maybe Justin and Tyler would have found some other connection and become friends. Maybe the academic support I offered Jeremy finally kicked in. Maybe not. Maybe the discussion of the science of skin tone and the praise of our beautiful differences facilitated these important transformations. I prefer to attribute my students’ growth to the poems in celebration of skin tone. Regardless, I plan to continue teaching in ways that might interrupt racist hierarchies and might do so joyfully.

Resources

- Hamanaka, Sheila. 1994. All the Colors of the Earth. Morrow Junior.

- Kissinger, Katie, and Wernher Krutein. 1994. All the Colors We Are: The Story of How We Get Our Skin Color. Redleaf.

- Showers, Paul, and Kathleen Kuchera. 1991. Your Skin and Mine. HarperCollins.

- Thomas, Joyce Carol, and Floyd Cooper. 2008. The Blacker the Berry: Poems. HarperCollins.

All the Colors of the Earth

Children come in all the colors of the earth

The roaring browns of bears and soaring eagles,

The whispering golds of late summer grasses,

And crackling russets of falling leaves,

The tinkling pinks of tiny seashells rumbling by the sea.

Children come with hair like bouncy baby lambs,

Or hair that flows like water,

Or hair that curls like sleeping cats in snoozy cat colors.

Children come in all the colors of love,

In endless shades of you and me.

For love comes in cinnamon, walnut and wheat,

Love is amber and ivory and ginger and sweet,

Like caramel and chocolate and the honey of bees,

Dark as leopard spots, light as sand

Children come in all the colors

of the earth and sky and sea.

—Sheila Hamanaka

Copyright 1994 by Sheila Hamanaka. Used by permission of HarperCollins Publishers.

My Skin

My skin is sweet cinnamon mixed with cream.

It’s the color of sand dollars on the ocean floor.

It’s like spicy sugar.

It’s like light caramel

It’s also like a heron’s neck.

My skin is the lion’s eye.

And it’s like a slithering viper on freshly mowed grass, pebbles under the desert sun.

My skin is beautiful

like my father’s and mother’s.

—Teddy

What Color Am I?

I am delicious mocha with a hint of cinnamon

I am warm caramel in the bottom of the bowl

I smell like spice cake baking in the oven

I am a spicy cinnamon latte.

–Sadie

My skin is not white

It is caramel whip,

sandy beaches

and the sound of pebbles under the desert sun

My skin is the warmth of the summer sun

And the promise of a day filled with joy.

—Malcolm

This article appears in our new book, Rhythm and Resistance: Teaching Poetry for Social Justice